Sara Hassan reviews key evidence of changes in young people’s trajectories from education to employment in the West Midlands. The blog starts by explaining the UK context and then discusses key challenges and most effective recommendations.

A selective review of research suggests that young people are not developing the relevant skills for the future labour market in the current education system and that certain sectors are worse affected than others, notably STEM, which has significant skills shortages. Much of the research also highlights the importance of appropriate careers guidance for young people in addressing skills shortages in addition to better connections between education and employers.

This blog reviews the shortages in the labour market and how the education system has an impact on this. In many reports, there seems to be a disconnect between the sectors that young people aspire to work into the jobs available highlighting a disconnect between aspiration and opportunity.

Context

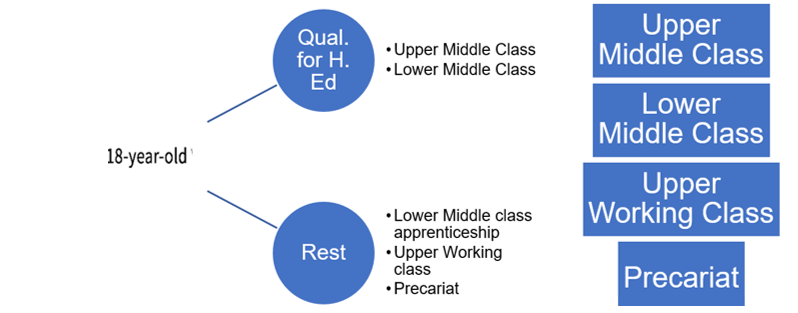

A Journal Paper by Ken Roberts shows that England’s current transition regime keeps rates of youth unemployment and NEET below the European Union averages and delivers the fastest transitions of education-to-work in Europe. Roberts explains that young people today are divided into two groups when they enter the changed transition regime, at age 18. They are the majority who have the qualifications for higher education and the rest. There are now four employment classes to which young people can head: an upper middle class that is entered through careers into elite management and professional occupations, a lower middle class who are employed in offices and laboratories, a new upper working class, and a precariat. See the figure below that explains these routes. The activated routes are as follows:

i. University into elite careers

ii. University into the lower middle class

iii. Exit education at 18 and enter the lower middle class, possibly via an apprenticeship

iv. Exit education at 18 and enter the upper working class, possibly via an apprenticeship

v. Fail in education and join the precariat

Figure 1: showing the new Transition Regime

Read more of this journal paper about integrating young people into the workforce here.

Challenges of Youth Education and employment

1 – Aspirations and Jobs Disconnect

The 2020 report from Education and Employers Research investigates the disconnect between young people’s career aspirations and jobs in the UK. It reveals that the sectors that young people aspire to work in differ greatly from the jobs available – highlighting a disconnect between aspiration and opportunity. The majority of young people are certain about their job choices – but there is a three-fold disconnect or worse between aspirations and demand in almost half of the UK economy. For instance, five times as many young people want to work in art, culture, entertainment and sport as there are jobs available. Over half of those respondents do not report an interest in any other sector. Young people are confident in their choices and the disconnect is strikingly similar at age 17/18 as at age 14/15, with similar patterns to the jobs to which children aspire at age 7/8. Such certainty and consistency of young peoples’ career choices throughout their teenage years suggest that this disconnect from available jobs, and the frustrations and wasted energy it produces, will require significant effort to resolve.

Read more about this disconnect between career aspirations and jobs here.

2 – Shock events: Pandemic and Brexit

The experiences of Britain’s COVID cohort show that the government’s “no detriment” policies (students who were approaching the end of their undergraduate courses in 2020 were assured that they would suffer “no detriment”) protected students from facing crucial examinations, and employees already in jobs were protected through furloughing. However, new entrants to the labour market were relatively unprotected.

Read more about this work here.

Yet despite the economic turbulence induced by the pandemic, lockdowns, followed by a “hard” Brexit at the end of 2020, rises in youth unemployment were confined to students seeking part-time jobs, and among them to particularly vulnerable groups, namely the least qualified and non-white ethnic minorities (The Cabinet Office, 2021).

3 – Race and Gender Inequality

In 2021, a paper by Eseonu highlights another challenge with the race and opportunity structures constraining racially minoritized (RM) young people’s transition to employment. For some young people, there has been continuity in terms of the persistent racial inequalities in employment outcomes. The presence of race structures in the labour market has seen RM people marginalised from the labour market. Marginalisation occurs because racialised schema in social relations determines how members of one group treat members of another group. The government’s race disparity audit shows that RM groups are more likely to be unemployed or underemployed and earn the least (Cabinet Office 2017). Race structures are central to understanding the differential experiences of RM young people’s transition to employment. Read Eseonu’s paper here.

4. Digital Skills Gap

Digital skills are key to the future of the labour market in the UK. The literature highlights how crucial digital skills will be for the future of the UK economy noting that young people must be supported to attain these skills. The take up of computing qualifications in schools and further education shows a significant interest among young people in pursuing a career that requires digital skills. However, there seems to be a gender gap in wider surveys of young peoples’ perceptions of digital subjects, in young peoples’ participation in digital training, and in the digital tech sector too. There is significant interest among young people in pursuing a career that requires digital skills. Half (51%) of young people say that they are attracted to a career that requires advanced digital skills. There is particularly strong interest among young males (62%), among young people in London (56%) and the East Midlands (56%), and among young people on an apprenticeship (61%). The pandemic may have increased interest in this area, with one in two (51%) young people saying that it made them more likely to consider a career requiring advanced digital skills. there is a significant gap in interest in a digital career. Three in four (62%) young males say that they are interested in pursuing a career that requires advanced digital skills, compared to just two in five (42%) of young females.

This gender gap is visible both in wider surveys of young peoples’ perceptions of digital subjects, in young peoples’ participation in digital training, and in the digital tech sector too. Figure 4 below highlights data from a recent Department for Education survey of 15 and 16 year olds’ attitudes towards STEM subjects. It shows that young males are three times as likely to say that IT is their best subject, and that it is the subject most likely to lead to a job. Young males are four times as likely to say IT is the subject they most enjoy, and they are over five times as likely to say that they plan to take an IT subject (computing, computer science, IT) at A Level (DfE 2019).

Digital apprenticeships are relatively rare. There are geographic inequalities in digital skills with London having a particularly thriving digital tech sector.

Read more about the digital skills gap here.

Focus on Birmingham and West Midlands

Young people find that they do not have the relevant skills required for progressing in certain sectors despite having studied in FE and that too much skills provision is still at a low level. There can be significant variations in the incidence and density of skills shortages within regions, showing that in the West Midlands, for example, an overall 20% of vacancies were hard to fill due to skills shortages, this reached 37.4% in the Black Country LEP area compared to 18.2% in the Greater Birmingham and Solihull LEP and 15.9% in the Worcestershire LEP.

Read the full report here.

In order to improve the skills of its residents, Birmingham should focus on three areas: improving the life chances of young people by focusing on early years education uptake and literacy and numeracy across all age groups; setting up the West Midlands Skills Fund to provide more tailored and targeted employment and training programmes, and providing better career guidance to young people; and making the city more attractive to high-knowledge businesses to increase job opportunities for graduates from Birmingham but also from the rest of the country.

Read the full report here.

Recommendations

There needs to be an over-arching strategy to prevent exclusion and promote participation amongst young people that are not in education, employment or training (‘NEET’), or at risk of becoming so. Interventions generally built on strong evidence from previous programmes, and targeted participants that were somewhat closer to work (i.e. motivated to work and likely to be looking for work) are usually more successful. However, interventions need to have a strong focus on progression to employment, close links with employers, close performance management internally and externally, and a strong ‘brand’ and presence.

The literature shows that much more needs to be done to ensure that all young people have access to high quality, independent impartial careers advice and guidance so they can understand the opportunities available to them, regardless of their background. Young people’s aspirations and planned pathways to their desired jobs need to be engaged with and, if necessary, constructively challenged. It should be supported by better and more accessible projections of labour market demand – showing likely levels of competition in particular jobs and sectors. The results suggest starting in secondary education is too late.

To mitigate the risk of legitimising discrimination employees within employment support services can assert their agency to dismantle race structures, thereby benefitting RM young people. Employees can start to dismantle race structures via employer engagement. Employer engagement involves building and maintaining trusting inter-organisational relationships with employers.

This blog was written by Sara Hassan, Research Fellow, City-REDI / WMREDI, University of Birmingham.

Disclaimer:

The views expressed in this analysis post are those of the authors and not necessarily those of City-REDI or the University of Birmingham.