By Dr Paulina Ramirez, Lecturer in International Business and Innovation

Department of Management, University of Birmingham

Giving employees, whose futures are tightly linked to the long-term development of their firms, not just ownership, but also voice in both strategic and day-to-day managerial decisions, could open the way to the retention of profits.

National systems of corporate governance – meaning the way that firms are owned, directed, financed and made accountable to society – critically influence the way that firms and industries develop new technologies that contribute to their innovative production processes. With this in mind, the announcement by John McDonnell that under a Labour government employees could become part-owners of large firms, even holding decision-making powers, could have significant implications for industrial innovation in the UK.

Sectors and innovation activity

Research into the impact that corporate governance has on innovation has shown that the visibility of innovative activities to people who aren’t directly engaged in the development work varies significantly according to industry. In industries such as pharmaceuticals, firms have research and development (R&D) laboratories, they make public announcements of their scientific collaborations with universities, and they patent their discoveries.

On the other hand, in sectors such as mechanical engineering and industrial design, innovation is often the result of daily activities that take place on the shop floor where engineers and production workers solve problems through trial and error, leading to the improvement of products and production processes. These types of innovative activities are much less visible to senior managers and even less so to distant shareholders and financiers who are not engaged with any level of productive activity.

At the same time, many of these activities have a long pay-back time, requiring owners and investors who are willing to wait many years for a return on their investments. These characteristics of the innovation process can result in serious under-funding of innovation projects in firms that are owned by distant and non-engaged shareholders.

Distant and non-engaged owners compromise innovation in UK firms

In the UK, since the mid-1980s, the main characteristics of the corporate governance system have been the dominance of financial institutions in the ownership of firms and a management system almost exclusively focused on the maximisation of shareholder value over short periods of time.

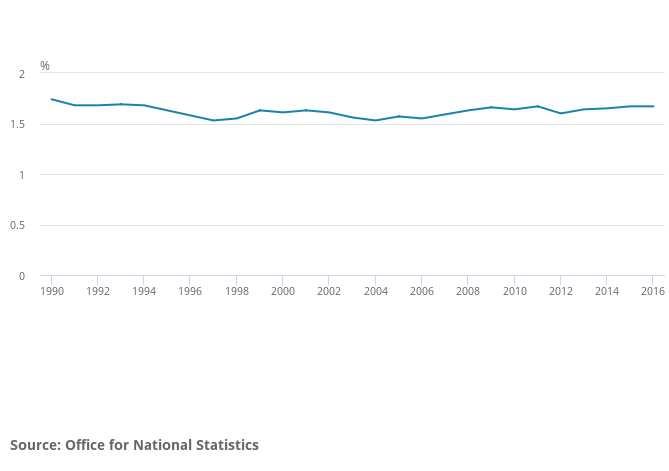

Figures from the Office for National Statistics (ONS) show that in 2016, 54% of the value of UK shares was owned by overseas investors, the majority of which were international financial institutions. UK financial institutions owned a further 27.6% of UK shares (see figure 1). This dominance of financial institutions in the ownership of UK firms has often been held accountable for the decreased investment in R&D as a percentage of GDP (a measure of the value of all goods and services produced) between 1990 and 1997, and for the low levels of R&D expenditure between 1998 to 2016 (figure 2), levels well below the EU average.

This is because, in general, the financial institutions that own UK firms see themselves mainly as traders of shares rather than long-term owners of companies. These owners are far more focused on the short-term movements of share prices than the long-term investment needs of the companies whose shares they own leading to the under-funding of innovation.

Employees as engaged and long-term owners

Giving employees, whose futures are tightly linked to the long-term development of their firms, not just ownership, but also voice in both strategic and day-to-day managerial decisions, could open the way to the retention of profits. This will help to ensure the long-term investment required for innovation, but also significantly increase the levels of owner and managerial engagement, which will support the critical but less visible innovative activities that take place in the workplace.