By Professor Aditya Goenka

The Department of Economics, University of Birmingham

There will be a crisis if the fears about the nature of the new variant are realised.

The news of rising infections and protests against control in Europe have been overshadowed by the report of the Omicron (B.1.1.526) variant. Despite its inclination for no measures for controlling Covid-19, the UK Government has reintroduced mandatory mask wearing in stores and public transport (but not in pubs and restaurants), RT-PCR testing, and possible quarantines for those entering the country. The news of the emergence of this variant had an immediate financial impact, with financial markets on Black Friday (26th November) having the biggest daily fall in 2021 and oil prices falling 13%.

Even though the WHO called for calm, many countries, including the UK, suspended flights to southern Africa, and Israel is blocking all foreigners from entering the country. Are these reactions warranted and what implications does this have for coming months?

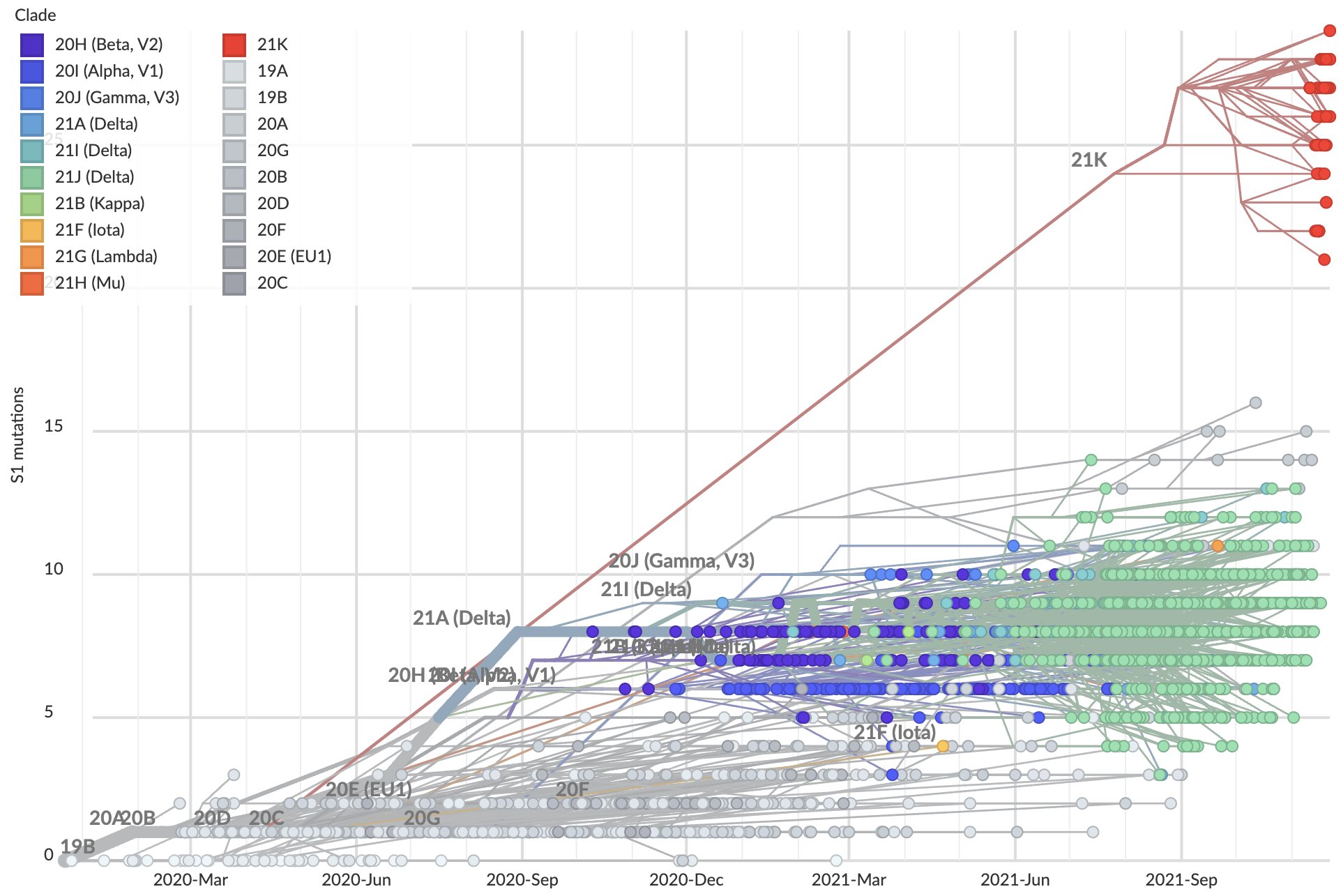

The Omicron variant has over 50 mutations and between 10 and 30 in the spike protein, which the virus uses to bind to hosts. Most of the existing vaccines target this spike protein. Thus, there is concern that the new variant will escape the coverage provided by vaccinations.

The new variant was first identified by genomic sequencing of a cluster of cases in Botswana and South Africa. It was also noticed that one of the genes, the S-gene, is missing in the genetic sequencing. A small number of cases would not be a cause of concern as there are many mutations that do not establish in the population. However, when recent RT-PCR tests in South Africa were re-examined, many were seen to be missing this S-gene. This suggests that this variant was spreading rapidly.

The financial markets, anticipating the government responses of re-imposition of lockdowns and travel restrictions, reacted immediately to the news. The losses were concentrated in sectors most exposed to restrictions – travel, banking, and hospitality – as well as the oil market.

Experience of control of the pandemic shows that early response is important, especially to prevent a new variant establishing in the population. For many countries, it is relatively easy to impose travel restrictions on the region as it is isolated geographically and economically. There will be less political and social pressure against isolating this region. This is to be contrasted with the slower response of UK to the emergence in the past to new variants, both last Christmas as well as to the Delta variant which was first identified in India.

We do not know to what extent the new variant escapes immunity from vaccination, whether it leads to more severe infections, or is more transmissible. If we do not know the probability of these events, and the cost of imposing these restrictions is low, then economic theory would suggest that the likelihood of the worst outcome should be minimised.

Will these early measures be successful in controlling infections in UK? It is too early to say, but signs are not encouraging. The messaging from the government is conflicted – the Prime Minister, the Cabinet, as well as the Conservative MPs have shown a reluctance to wear masks even when evidence indicates that wearing masks reduces transmission. Masks are required in public transport and in shops but not in restaurants and pubs. In this environment, even though there is high public support for wearing masks in UK, their use is currently low.

There is reluctance to impose or encourage working-from-home when other European countries are moving to it before Christmas. Most infections take place from prolonged close contacts – within homes, workplaces, or other venues. Measures such as improving ventilation in workplaces, schools and universities have not become mandatory.

There will be a crisis if the fears about the nature of the new variant are realised. The reaction in the UK has been a convenient one, avoiding hard decisions which could reduce the likelihood of a crisis – such as extending boosters to under 40s, second vaccines to teenagers, vaccinating 5-16 year olds, imposing anticipatory social distancing, and consistent messaging that the pandemic is not over.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham.