By Dr Alessandro Gerosa

Department of Marketing, University of Birmingham

On 15 March 2020, while Italy was in the midst of the despair caused by the first Covid-19 wave, an Italian magazine reported a very puzzling news: Giuseppe Conte, the Italian Prime Minister, was the most searched query on the Italian Pornhub. Highly read romantic fanfictions on him also flourished on Wattpad, the famous platform for amateur writers. The cause of this ridiculous escalation was no sexual scandal or ambiguous behaviour, but a page of Internet memes on Instagram named Conte’s babes. Devoted to share Internet memes of Giuseppe Conte with kitsch hearts and mushy captions, it rapidly gained astonishing followers and fame.

The viral diffusion and reproduction of these memes and tropes caused the birth of a ‘memetic cult of personality’, centred around Conte as the reassuring and devoted father of the nation during the pandemic, with the parodic, satiric, and irreverent twist intrinsic to memes. But the memetic cult of personality about Conte is not an isolated case. Rather, it was only the latest example of a currently highly relevant phenomenon. When Trump was elected president of the United States, his now infamous alt-right supporters celebrated the victory in what they considered the ‘Great Meme War’. They made Trump the object of a memetic cult of personality, exalting him as their ‘God Emperor’ for which they fought. At the other end of the US political spectrum, Bernie Sanders’ campaigns benefitted from the viral spread of memes about him created by fans on Reddit, Twitter and Facebook. Memetic cults of personality are not exclusive to Western politics: in Russia, memes have been used both by Putin supporters to exalt him and by political dissidents to mock him; in China, the (mostly satiric) ‘Toad Worship’ memetic cult of personality arose around former leader Jiang Zemin.

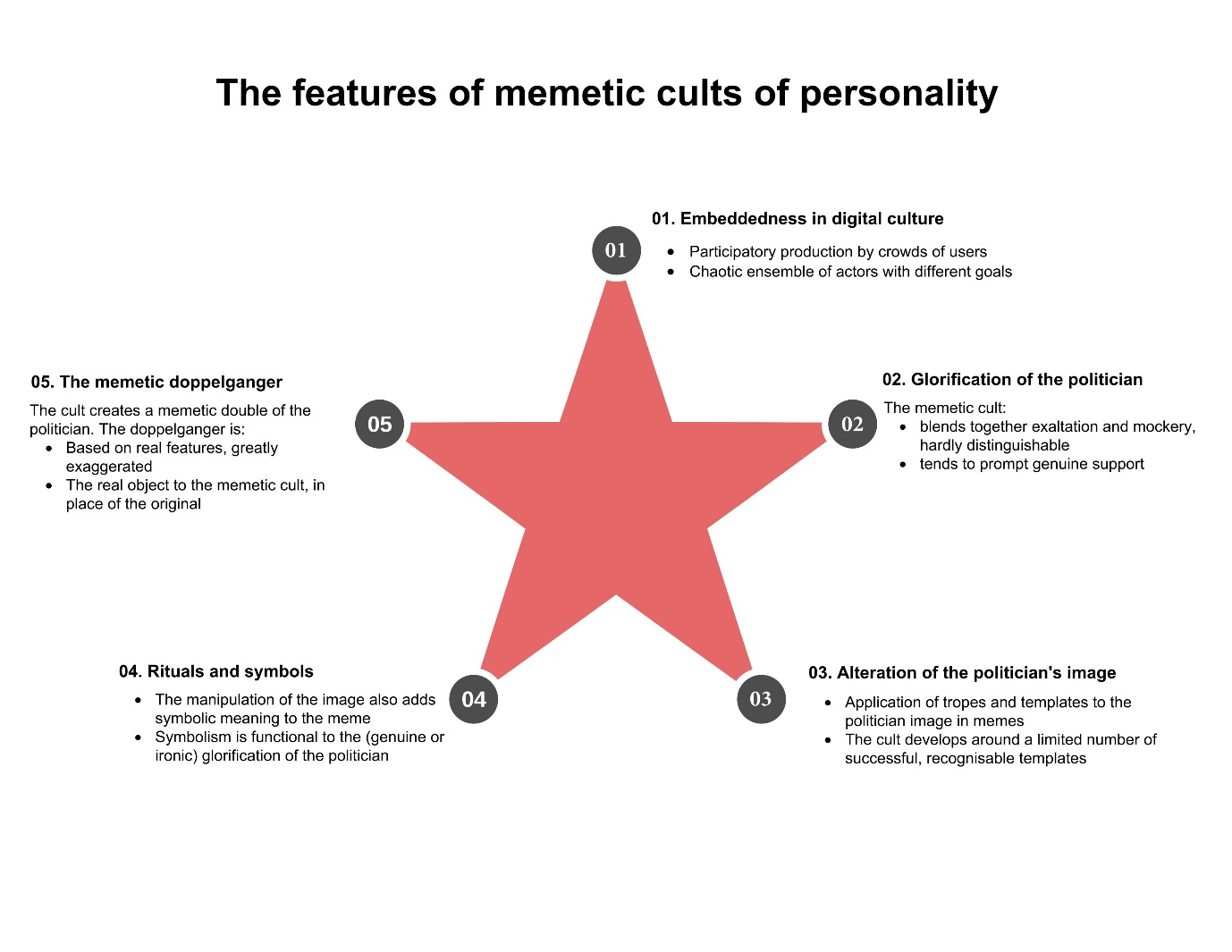

These examples show a great variety in the birth of memetic cults. Some arise from organised groups, or even campaign specialists, to support a leader; some as plain humorous, almost apolitical content; some as satire to mock powerful politicians. However, once they become viral, they take on a life on their own and become manipulable and usable by other actors with their own agenda. Memetic cults are proteiform: depending on the producer and the reader’s eye they can represent humour, satire, or exaltation (covert or explicit). Furthermore, often the birth and success of memetic cults derives from the collective outcome of a crowd of autonomous (and usually anonymous) users, forming a network too complex to disentangle. They worship not the original politicians, but their ‘memetic doppelgangers’, i.e. a caricatural version of them.

In a journal article published on ComPol, based on the case study of Giuseppe Conte and the similar one of Campania’s governor Vincenzo De Luca, Giulia Giorgi and I proposed a definition of this phenomenon, summarising the main features of memetic cults of personality, as reported in the figure below. With it, we hope to spark a debate on the topic. Internet memes have become defining cultural products of digital cultures. In the age of hyperleaders, their application to political communication brought to peculiarly innovative forms of fandoms. But the same underlying mechanisms bringing memetic cults of personality to birth in the sphere of politics are at play in every digital communication domain and could be of great interest for marketing and consumer researchers too. How corporate marketing could foster memetic cults directly or leaning on consumers collectives? Or, assuming a critical perspective, how can we deconstruct and unveil the way collective recreational production of internet memes is seized and exploited by capitalism? These are – I believe – critical questions to address in the digital age, whose answers are yet to be written.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham.