By Professor Stan Siebert, Professor of Labour Economics

Department of Management

The BBC reports that over the past year, pay rises on average have failed to keep up with the cost of living. At the same time, we know that in April OFGEM will be raising its energy price cap, perhaps by over £500, and inflation everywhere is looming. What are we to expect? Is this a blip or should we toughen the energy price cap and perhaps even bring in further price controls?

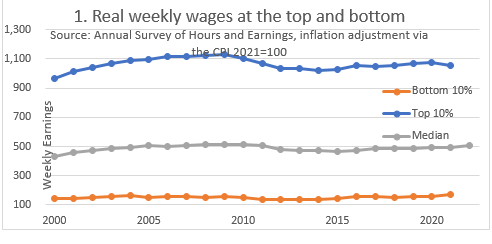

It is necessary to keep things in perspective. For those of us with jobs, even the lowest paid have maintained their position over the past few years. Looking back over 20 years, weekly pay for the lowest-paid 10% has increased by about £20 a week valued at today’s prices (see Chart 1). This position has been maintained even over the past 2 difficult years. If anything, it appears that only the top earners have a recent real pay cut. In general, we see stability. It then seems as though employers competing for a reasonably fixed supply of workers can maintain wages even at the bottom.

Factors such as the UK’s highly-educated workforce and good investor protections, which have led in the past to high investment inflows, have helped us. Of course, we cannot rely on these beneficial forces in the future. But barring unusual events such as another virus, or worse relations with the EU, we can expect the trend of slowly increasing real wages to continue.

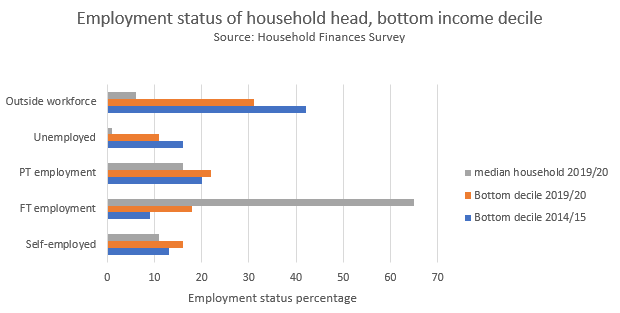

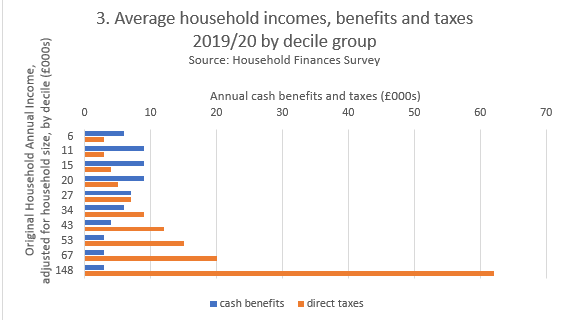

However, there are many people without jobs, and here the picture is more worrying. The UK is a very unequal society. Looking across all the households, not just those with jobs, we see that the bottom 10% of families have an income of only £6,000 a year (see Chart 3). This is because not many household heads in this group have full-time jobs, and while there are part-time jobs and some self-employment, about 40% in 2019/20 were unemployed or out of the workforce (see Chart 2). This is far more than the median household where almost all heads are in work. At least the position has improved. As can be seen, the percent in full time employment has almost doubled since 2014/15, but it is still worryingly low.

Of course, many household heads cannot work because of family responsibilities, and here the welfare safety net is even more important. As can be seen below, for the poorest families, incomes are doubled via cash benefits. In addition, there are further vital non-cash benefits such as the NHS and social housing (assisting about 40% of low income families). In fact, the UK seems to compare well with other countries with regard to family benefits, spending around 3% of GDP on such benefits according to the OECD where the average is only 2.1%. But these families still must face some council tax and remain terribly at risk from price increases.

At the other end of the scale, there are the richest families. These generally have two highly-skilled earners, producing annual family incomes of £148,000 and more. There is perhaps room for families in this enviable position to contribute more – however, these families contribute £60,000 in annual taxes. In fact, we see that it is only families earning more than the median whose taxes exceed benefits. In other words, only about half our families make a net payment to the exchequer.

The UK is already highly taxed, and while there may be some rearrangement – particularly if inflation becomes strong – our inquiry must return to jobs and how to reduce barriers to parental employment. Jobs are the answer.

In fact, the UK compares badly with other countries in the percentage of children brought up in families without work. The UK has about 15% of children under 14 brought up in jobless households, twice the OECD average. We need to look at the availability and cost of childcare as in Scandinavian countries. More difficult is rebuilding informal childcare networks via the extended family as in Greece and Portugal. These are difficult policy issues taking us beyond wages and the operation of labour markets which generally work well.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham.