By Jiaming Li (PhD Management), Dr Edward Granter, Dr Andy Hodder

University of Birmingham

Thus, content creators are autonomous and independent, yet fight against the surveillance and regulations of platforms.

With working from home becoming the ‘new normal’, the Covid-19 pandemic led to increasing recognition of social media as a form of employment and entrepreneurship. At the same time, marketing through social media ‘influencer’ channels surged to a worth of $9.7 billion (5% of the total online advertising market) in 2020.

Many firms are increasing their expenditure on this industry, with 67.9% of US marketers saying they had used social media sites for brand promotion in 2021, and 72.5% of marketers saying they will use platforms in 2022. Meanwhile, traditional employees, like chefs in restaurants, used social media as an opportunity for diversification and additional revenue during this uncertain time. While many celebrate the rise of a new class of ‘content creators’, details about their self-perception, work identity and economic security remain scant.

In the case of those put out of work by critical incidents such as the pandemic, we can say that necessity is the mother of invention. However, the work of online content producers also appeals to those concerned with autonomy and flexible working time. Duffy (2017) describes this as aspirational work because pleasure and work coexist. Online content producers interpret their involvement in content production (whether voluntary or as a survival strategy) as playful experiences. Yet, creators must also learn how to capitalise on the elaboration of their image, creating a sense of intimacy, which merges with advertising. All these attempts require intensive, time-consuming multi-tasking and emotional work – yet remain essentially unremunerated, at least at first. Platforms, like YouTube, have various infrastructures that convert play into money-making, and therefore these ‘amateurs’ believe that their unpaid or partly paid work will be compensated and they will become ‘professional’ content creators.

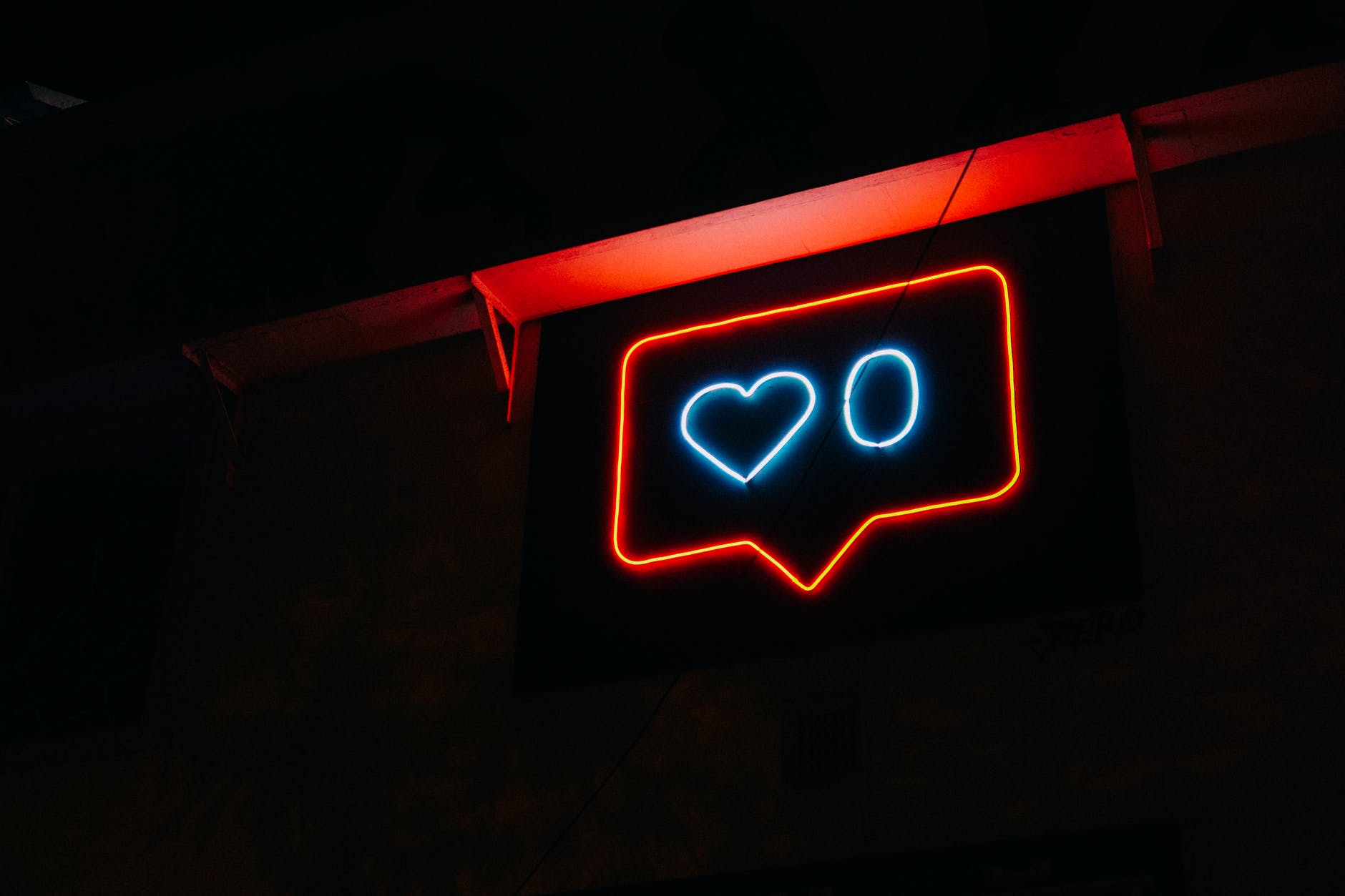

In many cases however, autonomy and flexibility for creators are elusive, due to the competitive social media world, which demands content creators maintain a constant presence on social media. Despite this reality, many users on social media are taking fame and fortune and the promise of success for granted. They believe that everyone can become an influencer on social media. Strategically performing and building online images, intimacy and authenticity are common, but success requires updating and frequent contact on the platform. Temporality has been sped up alongside the constantly changing environments of media, which requires being ‘always-on’. A creator becomes both the one doing the work and the enterprise itself. For some, these online environments contribute to irregular working pace and poor work-life balance.

Additionally, being an influencer means being an entrepreneur who draws attention to their distinctive achievements. For example, fashion bloggers often express entrepreneurial identity on their social media channels. However, many influencers are also self-employed freelancers whose ‘identity work’ is part of the revenue stream – via monetisation – of social media companies. YouTube launched its YouTube Partner Program in 2007, which distinguished creators eligible for advertisement revenue sharing. A Chinese platform, Kuaishou, has the same regulations, and extracts 50 % of the ‘gifting’ income generated by producers.

In this context, and under the algorithmic surveillance of platforms, enhancing one’s visibility and ability to capitalise on it is crucial. Bishop (2021) interprets the search for visibility as an attempt by content creators to understand how algorithms work. Thus, content creators are autonomous and independent, yet fight against the surveillance and regulations of platforms.

Overall, the fluid and flexible features of online content creation contribute to a sense that content creators are not in fact a new ‘class’ of workers. Influencers encounter problems with rights and an imbalance between platforms and creators, which has created an embryonic drive for greater solidarity and recognition. Yet, the unionisation of influencers is certainly not imminent. As the spirit of self-entrepreneurship among producers is ubiquitous, the antagonism between creators and the platform tends to be disguised. Becoming an influencer can seem like the ultimate career choice, but freedom from the daily grind, or from commercial imperatives, may be more elusive than they seem.

- Find out more about Dr Edward Grant at the University of Birmingham

- Find out more about Dr Andy Hodder at the University of Birmingham

- Back to Business School Blog

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham.