By Edward Pinchbeck (University of Birmingham), Dr Felipe Carozzi (London School of Economics) and Dr Luca Repetto (Uppsala University)

The two world wars of the early 20th century are an indelible part of Britain’s public consciousness, cultural identity, and shared memory. One way in which past wars endure in social and political discourse is through commemorative acts and symbols. In Britain these can take on immense scale, as illustrated by the 30 million commemorative poppies that are produced by The Poppy Factory each year.

Aside from their popularity, commemorative activities and symbols that are associated with past wars may be important for at least two reasons. First, narratives surrounding them may be contested or politically charged. For example, David Cameron’s statement that that the First World War Centenary (FWWC) should be a cause for celebration was scorned by some commentators; UK Independence Party (UKIP) logos on remembrance wreaths caused controversy in 2013; and the wearing of a poppy in sports events led to intense debate and international divisions in 2016. Second, it is possible that commemoration can encourage pro-social or civic-oriented attitudes and behaviour. For example, an estimated 9.4 million volunteers took part in community heritage projects as part of the FWWC, and WWII veteran Captain Tom Moore became a fund-raising sensation in the early stages of the pandemic.

The mass commemoration and remembrance of war in Britain began in earnest during the inter-war period that followed the Great War of 1914-18. The sheer scale of the war and the deadly nature of trench warfare meant that close to a million British soldiers did not return home. Following the Armistice of 11 November 1918, the memorialisation of the war dead became a significant national concern: observed for example in the holding of a two minute’s silence, the ceremonial laying of wreaths at the Cenotaph in Whitehall, visits to the grave of the Unknown Warrior at Westminster Abbey and to the battlefields of northern Europe.

As well as national events, many local customs and traditions of memorialisation arose reflecting the diverse experience of local communities in the war. To honour their dead and to ensure that the sacrifice of their own communities was never forgotten, local groups raised funds to erect over 50,000 war memorials. These monuments, which can still be found in towns and villages throughout the country, plausibly served as tangible symbols of the human cost of the war and etched the memory of the fallen and their sacrifice into the very fabric of local communities.

Building civic capital

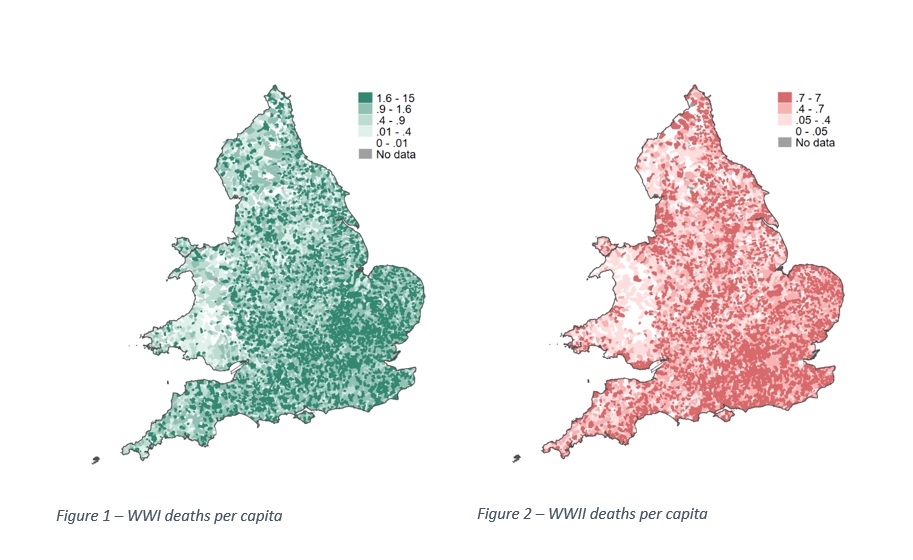

In a recent working paper, we explore whether sacrifice in past wars, and the way in which it is remembered, have lasting effects on local communities by changing the behaviour of subsequent generations. We examine this in the context of the two world wars. Specifically, we ask if sacrifice in World War I fed through the behaviour of subsequent generations of soldiers on the battlefield in World War II just 30 years later. Virtually all parts of England paid the cost of the wars but, as the maps below illustrate, not all communities suffered equally.

We hypothesise that past acts of sacrifice and their commemoration motivate soldiers’ actions because they foster values that encourage and normalise pro-social behaviour. Put another way, we conjecture that if you were raised in a community in which past generations are lionised as heroes for their self-sacrifice, you may value social above individual ends. Building on previous work, we refer to these shared community values as civic capital.

Various features of inter-war Britain suggest that the memory of WWI was used to motivate soldiers throughout WWII. For example, the 1939 Armistice Day radio message of the Queen Mother explicitly linked the two wars, “For 20 years, we have kept this day of remembrance as one consecrated to the memory of past and never to be forgotten sacrifice. And now the peace, which that sacrifice made possible, has been broken, and once again we have been forced into war…. We have all a part to play, and I know you will not fail in yours.”

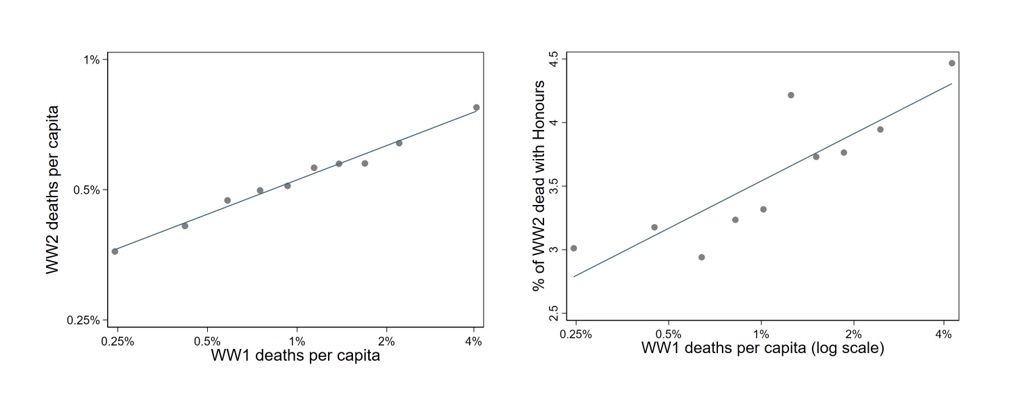

To test this hypothesis, we built new datasets from individual-level WWI and WWII death and service records. Our first major finding is that community-wide soldier deaths in WWI strongly predict a community’s losses in WWII, as well as the likelihood that local soldiers are awarded gallantry medals in that conflict, as shown in the graphs below. Critically, we use econometric techniques to establish that these connections are causal and are not being driven by inherent, pre-determined social and economic characteristics of communities or their residents, such as their health status or wealth levels.

The power of memory

Subsequent results provide strong suggestive evidence that these effects indeed run through past sacrifice leading to the formation of civic capital – that is, those shared values that emphasise co-operation and putting social above individual needs. For example, we establish that community deaths in WWI led communities to build higher quality war memorials (as measured by listed status) and to open more new charities and British Legion branches in the inter-war period.

Our findings also reveal a noteworthy relationship between World War I deaths and increased political engagement in subsequent elections, a widely used indicator of civic capital. Interestingly, we observe that the impact of WWI deaths on electoral turnout persists strongly, extending even two decades beyond the WWI, which is the endpoint of our available data.

All told, our results strongly indicate that past sacrifice and its remembrance can be powerful drivers for subsequent generations. Our findings have several implications, including that past wars can be complementary to other forms of motivation such as propaganda, or forced mobilisation. A darker interpretation is that war begets war, and the human costs of conflict can become concentrated in particular locations.

The extent to which the legacies of past wars still influence communities today remains an open question, and exploring the enduring effects of war in Britain is an ongoing focus of our research efforts. On the one hand, it seems reasonable to expect that the civic-oriented values that spurred on soldiers in WWII persist through to modern times through a combination of inter-generational transmission of values and the ongoing memorialisation of past wars. On the other, some have argued that the best and brightest of the WWI generation were lost on the battlefield, and that this may even have contributed to the subsequent decline of Britain as a world leader. The long-term consequences of the loss of talented young men for particular communities is as yet unclear.

This blog post draws on a recent working paper that explores the effects of World War I on British communities.

- This piece was originally published on London School of Economics and Political Science British Politics and Policy blog

- More about Edward Pinchbeck at the University of Birmingham

- Back to Business School Blog

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham.