Department of Strategy and International Business, University of Birmingham

The last year has proven to be challenging for the retail industry, with numerous firms either facing difficulties, closing stores, or retreating from the market entirely. Although such sectoral difficulties are not new, they were exacerbated by a sluggish festive period; due to poor Christmas sales in 2018, HMV entered administration, with other firms including H&M, House of Fraser, Debenhams and John Lewis & Partners also reporting a poorer financial performance than expected. Looking back over 2018, no UK regions experienced a net gain in store count over the first half of the year and the British Retail Consortium asserted that approximately 85,000 retails jobs were lost over the twelve months.

What are the main drivers of the ‘retail crisis’?

The media often cites Brexit as the cause of this decline, and although it is undoubtedly already leading to economic uncertainty and could result in store closures or underperformance over coming months, it is not an isolated driver and retail issues are not confined to the UK or Europe. Rather, we assert that there are six other drivers of the ‘retail crisis’ affecting our high streets:

- A squeeze in incomes

- The shift to online shopping

- Changing consumer tastes

- Rising overheads

- High debt

- Too many shops

These factors have affected other industries too, such as the hospitality industry in which restaurants such as Jamie’s Italian, Carluccio’s, Gourmet Burger Kitchen and Prezzo have all closed a number of locations and reduced their employee headcount. The ongoing nature of these issues perhaps signals that the ‘crisis’ is maturing. The most vulnerable outlets have already exited or been forced out of the market, which signals that those remaining are comparatively resilient. However, that does not mean that they are unaffected by the aforementioned drivers of change.

To keep or to sell

While the media continues to focus on big brands and their difficulties, as evidenced by recent headlines on Patisserie Valerie, there are interesting developments going on ‘behind the scenes’ with property development agencies and investment firms debating whether to hold on to or sell their property portfolios. With their retail clients experiencing reduced sales, landlords may begin to raise concerns, and in turn struggle to find new tenants if their current customers are unable to survive. In this way, the consequences of the ‘retail crisis’ can be felt in adjacent industries and ripple throughout the economy.

When retail firms face financial difficulties, they usually enter company voluntary arrangements (CVAs), a form of insolvency that enables businesses to renegotiate deals with their creditors – often landlords whom are asked to accept lower rent payments. Although such agreements could mitigate the current challenges facing retailors, this strategy just passes the burden along the value chain.

Hammerson: selling up shop

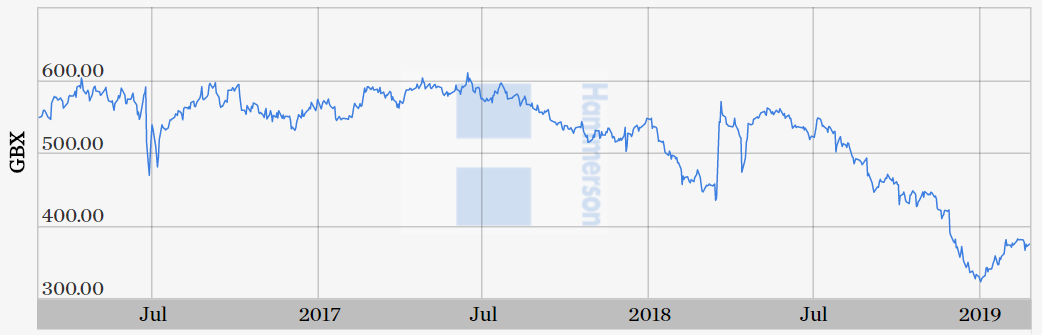

Hammerson, a giant property development and investment company that owns shopping centres such as Birmingham’s Bullring and London’s Brent Cross, has recently suggested that they may be selling over £900m worth of property given the severity of current environmental conditions. Among Hammerson’s tenants are Patisserie Valerie, which went into administration last month but was saved from closure by a management buyout backed by an Irish private equity firm, as well as House of Fraser and New Look. The latter two have already resorted to CVAs to avoid insolvency, forcing them to close a string of stores and seek rent cuts from their landlord. This news follows Hammerson’s sale of £570m worth of property in 2018, most of which were sold below their December 2017 valuations. The accompanying decline in Hammerson’s share price is worrying, falling approximately 50% between 2017 and 2019 (Figure 1).

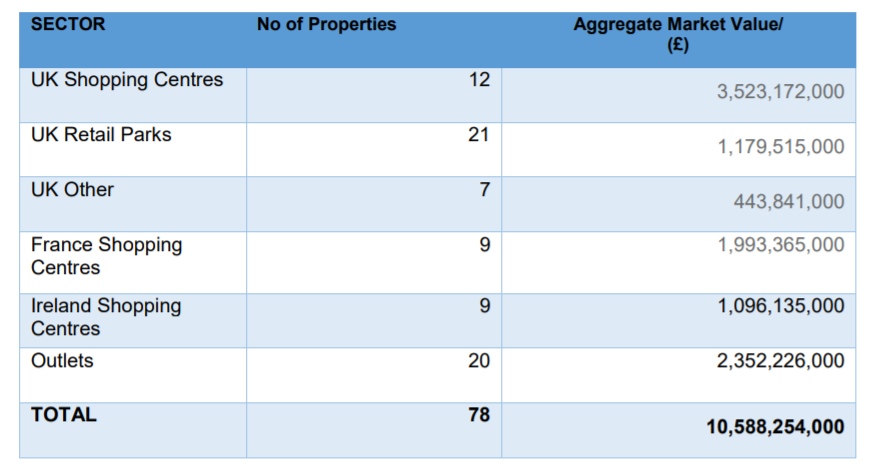

Although its name may be unfamiliar to the average customer, in 2018 Hammerson owned 78 properties across three countries, which had an aggregate value of over £10bn. The majority of these were retail outlets based in the UK, signalling overdependence on one market, particularly as the current (physical) retail climate is rather bleak. In 2017, Hammerson had approximately 5,000 tenants, whose stores were visited by 440 million customers that same year. With a 9.3% decline in Hammerson’s property values in 2018, it is no surprise that the US hedge fund Elliott Advisors, which owns a 5% stake in the Hammerson, are eager to sell more properties, including Birmingham’s iconic Bullring.

It seems as though Hammerson, along with its investors, has lost faith in the British retail market, and more specifically its tenants, resulting in this drive to condense its portfolio. While this may be worrying news for their retail clients, it is perhaps prudent of Hammerson to act now. The drivers of change we highlighted at the beginning of this article demonstrate inherent changes both in our purchasing behaviour and the dynamics of the retail industry. High streets are evolving and need to take these drivers into account. This may require firms to adapt their business models if they wish to maintain a secure high street position, perhaps following Primark’s example, whose new Birmingham store will include a beauty studio, incorporating face-to-face encounters into their value proposition to stave off online competition.

As it stands however, many high street retailers are not adapting to market forces, which in turn will affect their landlords who seek to avoid empty lots and ensure a return on their investment. While the high-street will not disappear, it may change in its function. With the shift to online shopping and the creation of out of town shopping centres, we do not rely on the high street in the way we once did, so perhaps it is time for a new iteration for this key place in our towns and cities, perhaps centred on experiential services.

While this may be a longer-term issue, we cannot ignore the short term. The withdrawal from the European Union is imminent and is presenting a number of economic unknowns. However, price rises are perhaps one of the few certainties, which could exacerbate pressures on consumer spending and in turn aggravate the financial difficulties of retailors. Therefore, it is understandable why Hammerson is seeking to retract from the market and sell properties to mitigate against future decline in property values and its share price. The issue is perhaps whether Hammerson is able to find a buyer in the face of current uncertainties.

With regards to the retail industry more generally, perhaps we are witnessing a new stage in the evolution of this sector, whereby current business models must adapt to survive. Retail firms no longer require multiple outlets in close proximity, particularly given the increase in online shopping and the high cost of prime high street locations that may not be providing a return on investment. Thus, in the shorter term, firms may be required to downsize or consolidate their outlets to reduce operating costs. More proactive decision-making could extend the current stage of the high street’s life cycle, and in turn reduce the proportion of firms seeking CVAs from their landlords, restoring the confidence of the likes of Hammerson.

Source:

- https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/business-46142025

- https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/dec/28/no-end-in-sight-to-uk-high-street-retailers-troubles

- www.hammerson.com

- https://www.theguardian.com/business/2019/feb/15/high-street-discounts-boost-struggling-retailers-brexit

- https://www.theguardian.com/business/2018/nov/09/embattled-high-street-retailers-call-for-help-as-closures-soar

- https://www.birminghammail.co.uk/whats-on/shopping/how-job-worlds-biggest-primark-15906621

- Back to Business School Blog

- More about Dr Emma Gardner at the University of Birmingham

- More about Dr Amir Qamar at the University of Birmingham