By Dr Johannes Lohse

Department of Economics, University of Birmingham

With the COP 27 summit ongoing, where do we stand with climate change, and what could a UK policy response look like?

Let’s begin with the good news.

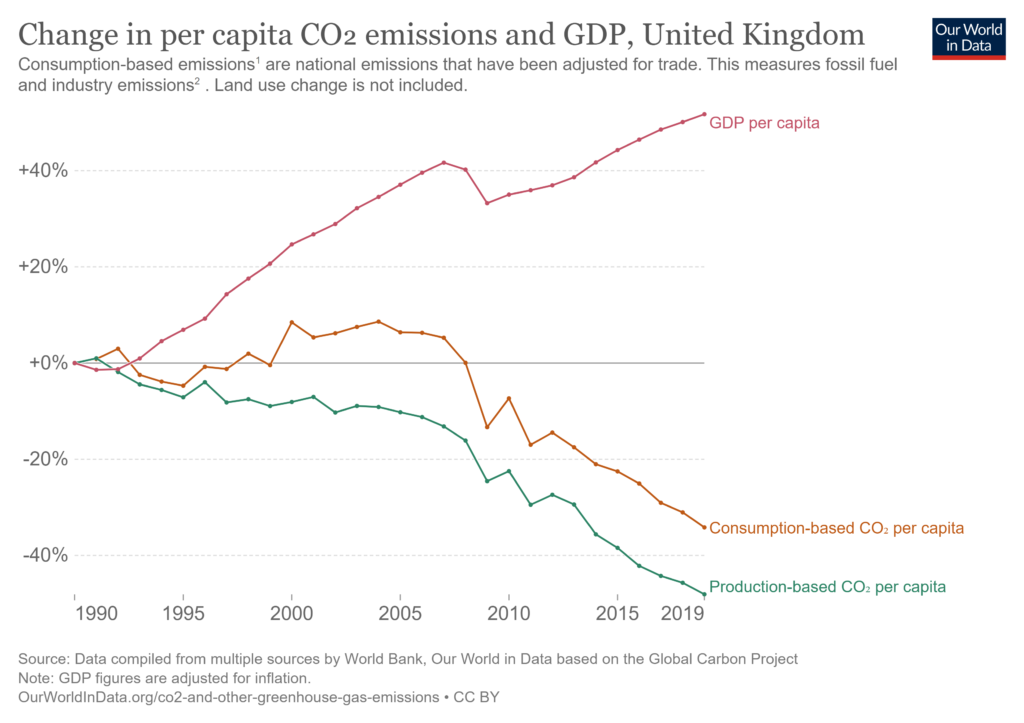

Carbon emissions in the UK and other western countries have been falling in the past decades, and there are hopeful signs of partial decoupling of emissions and economic growth. From 1990 to the beginning of the COVID pandemic in 2019, per capita GDP in the UK has grown by roughly 50%. During the same period, carbon emissions per head have fallen by 35-45%. This reduction is evident for production-based emissions and, importantly, also for consumption-based emissions – a metric that includes emissions from imported products.

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions

One part of the story is the sectoral transformation of the UK from a manufacturing-based to a service-based economy. More importantly, manufacturing has become less reliant on fossil fuels for both the goods the UK still produces domestically and for the goods it buys from abroad. The energy mix in many countries has become less carbon intensive, reflecting the dramatic drop in per unit costs of many renewable energy sources, with solar and onshore wind energy being at price parity with their fossil counterparts. A resurgence of nuclear power in the form of small modular reactors (SMRs) and advances in battery storage may provide additional options for low-carbon energy that is less dependent on fluctuations in weather conditions.

Now for the bad news.

Global emissions are still rising (although at slower rates, and potentially approaching a turning point). As highlighted in the latest IPCC report, without dramatic changes to the current emission trajectory, reaching the 1.5 degrees target is becoming increasingly unlikely, and even the 2 degrees target is in danger. To achieve these goals, global emissions must fall faster within the next two decades. In addition, in most 1.5 to 2-degree scenarios, negative emissions technologies such as direct air capture are necessary to remove some overshoot emissions from the atmosphere. While prototypes of the required technologies exist, current designs are not yet economically viable and building them at the necessary speed and scale would be a challenge.

So, what climate policies should the UK pursue, and what further ambitions are required?

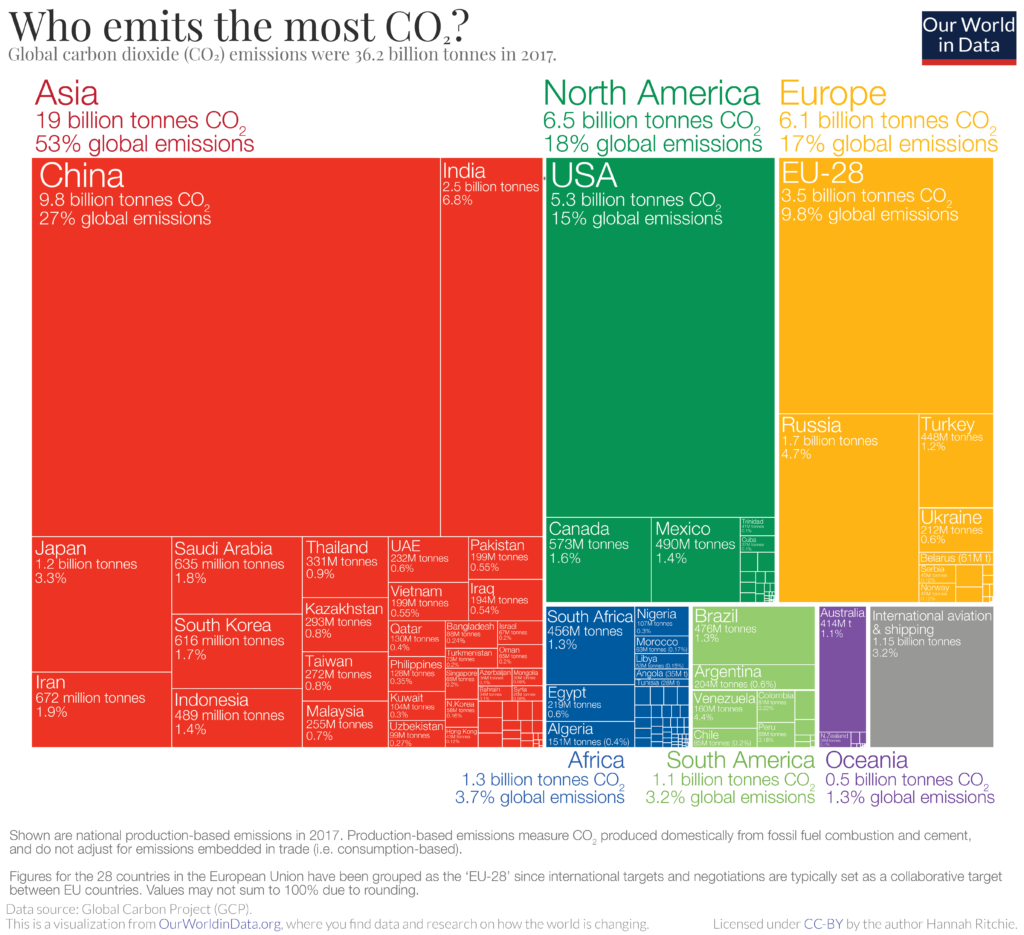

The UK is not a large country in terms of total annual emissions. Hence, reaching net zero unilaterally will have a marginal impact on climate change. This basic fact has been the core challenge of international climate negotiations since their early days. Limiting climate change is only achievable if all major economies reduce their emissions significantly. However, this means that the locus of control over global emission trajectories is quickly shifting to Asia, which already accounted for 53% of global annual emissions in 2017, compared to 18% in North America and 10% in the EU. A sluggish recovery from Covid, shifts in global supply chains, and tensions about security and trade issues will certainly make it harder to convince China to reduce its reliance on coal and other fossil fuels at a faster pace.

Source: https://ourworldindata.org/co2-emissions

In terms of concrete policies, as an economist, I still believe that putting a price on carbon emissions (via a tax or emission trading) is the single best instrument to reach the required emission reductions in the least costly way. In an ideal world, this price would be uniform across all countries, and policymakers would commit to a (rising) price trajectory that spreads the cost of mitigation across current and future generations and provides a credible planning horizon for firms. This is by far no new insight but the consensus among environmental economists for at least 30 years. Yet, recent discussions about high energy prices and the solutions proposed by policymakers make me sceptical that carbon taxes are well understood or liked by policymakers or the public. In this respect, it would be worth reminding citizens that carbon taxes are not only the least costly response to climate change but also provide additional and immediate ancillary benefits. As the price of fossil fuels increases, there will be a reduction in urban air pollution resulting from power generation, manufacturing and transport. A large number of studies, including some recent work from my colleagues, have demonstrated the many adverse effects of air pollution on human health, mortality and productivity.

Ultimately the speed of emission reductions will depend on the availability and cost of low-carbon technologies such as SMRs, hydrogen cells, direct air capture, advanced batteries, electric vehicles, and other technologies yet to be imagined. Funding basic research and supporting the commercialisation of low-carbon technologies is thus essential. Here, the UK government can help by coordinating efforts of private actors, providing financing for high-risk projects, widening access to STEM education and research, and removing barriers to innovation. When the price of solar power dropped below grid parity, worldwide adoption accelerated, showing that fostering innovation can change other countries’ incentives to commit to faster emission reductions. Similarly, widening access to low-carbon technologies for developing countries should be a key priority of current and future COP meetings.

Finally, it is important to acknowledge that even with significant commitments to mitigation, many countries will experience considerable climate change in the coming decades. Here, a major question is how well countries can adapt. Academic work in this area suggests we may have been too pessimistic about adaptation potentials. For instance, in the US, excess mortality during heat waves has declined by 75% in the second half of the 20th century, primarily due to the more widespread air conditioning.

Put simply, with sufficient resources, some of the worst impacts of a changing climate can be averted. However, adaptation can be a significant challenge for poorer countries because they lack the necessary resources, even when no elaborate technological solutions are needed. Fostering economic growth and providing direct financial assistance is essential for these countries to cope with the challenges that even 1.5 or 2 degrees of warming will result in.

- More about Dr Johannes Lohse

- More about the Department of Economics at the University of Birmingham

- Back to Business School Blog

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the author and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of the University of Birmingham.