In this post for the “BMI lockdown life” series, Lydia Craig (@lydiaecraig on Twitter) of the Loyola University Chicago delights us with more insights about Charles Dickens, the 16th president of the BMI. Lydia is co-organizer of the upcoming #Dickens150 virtual conference on 9 June. If you want to join this day of virtual talks and panels on Dickens’s life and work, you have the opportunity to register by 6 June.

The “BMI lockdown life” series (#BMILockdownlife) on 19th century culture is a collaboration with the Birmingham and Midland Institute. If you’d like to propose a guest post related to the teaching, research, and/or anecdotes of 19th century culture and literature, please contact us via email or Twitter.

Was Charles Dickens a dog or cat lover? The question occurred to me while conducting recent research into digitized nineteenth century works on HathiTrust, Internet Archive, and Google Books. Several quotes and anecdotes cast Dickens as fond of both canine and feline companions. In an 1865 letter, Dickens sympathizes,

The St. Bernard has been dreadfully ill of canker in the ear; and her human way of expressing her being in pain, and entreating [ ] sympathy, has been very moving indeed. (Dickens, Letters)

Later, in Charles Dickens by His Eldest Daughter (1885), Mamie recorded her father’s affection for a deaf and mischievous cat raised in his study, which repeatedly snuffed a candle with its paw to attract the author’s attention (Dickens, Charles, 107). This heart-warming tale is often retold in subsequent children’s stories, accompanied by a charming illustration (see Figure 1).

Recalling the strange outburst of Nicodemus Boffin to John Rokesmith about Bella Wilfer’s marital aspirations in Our Mutual Friend (1865), I wondered if examining dog and cat mentions in Dickens novels would clarify the issue by showing which was pictured more positively overall in characterization and imagery:

‘Win her affections,’ retorted Mr. Boffin, with ineffable contempt, ‘and possess her heart! Mew says the cat, Quack-quack says the duck, Bow-wow-wow says the dog!…’ (Chapter XV)

Regrettably, I have not explored Dickens’s portrayal of ducks, a topic for another researcher!

Searching for cats and dogs

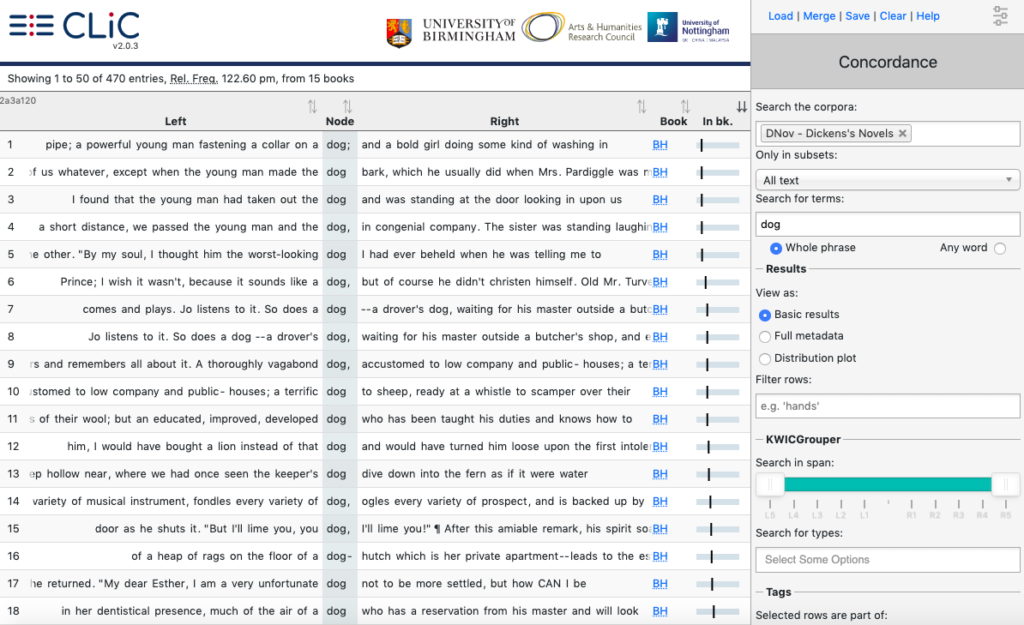

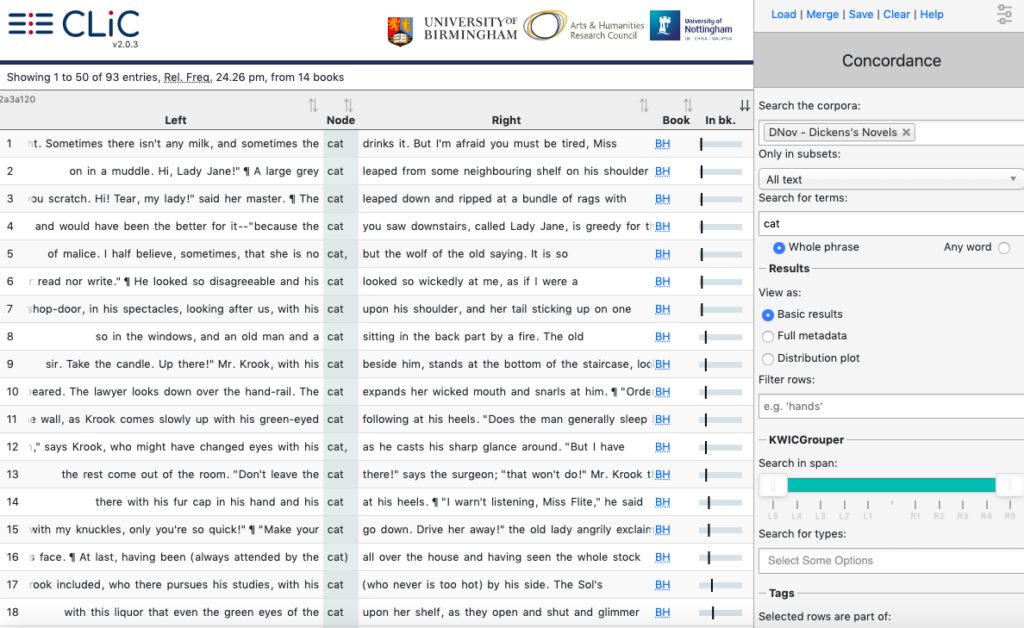

Using the CLiC concordance tool (Mahlberg et al. 2016) to search for dog across Dickens’s novels yielded 470 entries (see Figure 2), with an additional 150 for the plural dogs, and 10 variants (i.e. bull-dog = 5, canine = 5) for a total of 630 occurances. Performing the same search for cat yields 93 entries (see Figure 4), plus 30 for the plural cats and 5 variants (feline), a total of 128. Man’s best friend appears to be the clear winner by overwhelming odds of nearly 5 to 1! Lest feline-lovers despair, considering the data qualitatively provides a different interpretation of this lopsided ratio.

Many dog owners make a point of regulating the behavior of their canine companions, sometimes very strictly. Keeping a pack of dancing dogs as street performers, as seen in Figure 3, an illustration from The Old Curiosity Shop (1841), Jerry deprives them of supper if they fail to draw tips. Mr Henry Gowan of Little Dorrit (1861) beats his dog Lion unmercifully when he attacks the villain Blandois.

Predictably, novels which feature notable animal characters like Bill Sikes’ abused dog Bull’s-eye, generally experience an increase in references. Oliver Twist (1839) has the most instances of dog(s) in any novel (87):

Mr. Sikes…dropping on his knees, began to assail the animal most furiously. The dog jumped from right to left, and from left to right; snapping, growling, and barking; the man thrust and swore, and struck and blasphemed; and the struggle was reaching a most critical point for one or other; when, the door suddenly opening, the dog darted out: leaving Bill Sikes with the poker and the clasp-knife in his hands. (Chapter XV)

Not all owners are cruel; the otherwise unpleasant Hugh in Barnaby Rudge (1841) cares deeply for his dog. Anti-heroes like Sikes, Daniel Quilp (The Old Curiosity Shop), and Jonas Chuzzlewit (Martin Chuzzlewit, 1844) and posturing young males like James Steerforth (David Copperfield, 1850) often insult or compliment other male characters by calling them dog, reflecting the ambivalent connotations of this term.

Only one of Dickens’s novels omits any description of a real dog, the unfinished detective novel The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870). In A Tale of Two Cities (1859), except for mentioning the great dogs who nocturnally guard the imprisoned nobles, and aristocratic possession of great dogs prior to the French Revolution, dog(s) is mentioned only as a slur or simile for members of the lower class, while cat(s) only feature in similes. Realistically, the impoverished French are not able to spare extra scraps of food for animals.

No real cats appear in Nicholas Nickleby (1839), A Tale of Two Cities, or Edwin Drood, though the word occurs in similes. Great Expectations (1861) only includes one dream and one sighting of cats; Hard Times (1854) is an entirely “cat-free” novel except for a fleeting reference to the English nursery rhyme “The House That Jack Built.” Cats are mostly a comforting domestic presence. A rare gruesome moment appears in Little Dorrit when a comedic story is told of a cat crushed by a Royal Mail coach. Not funny, Charles!

Generally, cats are owned by women, as when David Copperfield plays with his Aunt Betsey Trotwood’s pet. When Dickens wishes to portray a topsy-turvy atmosphere, he reverses this formula, describing feline men and male cat owners. Mr. James Carker is a human cat in Dombey and Son (1848), marked by a wide grin and sinister movements. In Bleak House (1853), containing the most cat(s) mentions (30) of Dickens’s novels, lawyer Mr Vholes keeps a predatory office cat. Rag-and-bottle shop owner Mr Krook (see Figure 5) adores the malevolent Lady Jane, who terrifies bird-lover Miss Flyte:

“I cannot admit the air freely,” said the little old lady…“because the cat you saw downstairs, called Lady Jane, is greedy for their lives. She crouches on the parapet outside for hours and hours. I have discovered,” whispering mysteriously, “that her natural cruelty is sharpened by a jealous fear of their regaining their liberty. …” (Chapter V)

Occasionally, Dickens uses these two animals in conjunction to heighten a prevailing sense of exclusion, as also occurs in Bleak House. Baying of strange, invisible dogs echo in the misty air, an eerie reminder of guarded homes, while displaced cats flee an unidentified sound:

It has aroused all the dogs in the neighbourhood, who bark vehemently. Terrified cats scamper across the road. While the dogs are yet barking and howling–there is one dog howling like a demon–the church-clocks, as if they were startled too, begin to strike. (Chapter XLVIII)

In Dombey and Son, these animals belonging to other people become surrogate pets for children lacking parental love, Paul Dombey yearningly forming relationships with them:

The cat, and Paul, and Mrs Pipchin, were constantly to be found in their usual places after dark; and Paul, eschewing the companionship of Master Bitherstone, went on studying Mrs Pipchin, and the cat, and the fire, night after night, as if they were a book of necromancy, in three volumes. (Chapter VIII)

He deliberately overcomes his fear of Dr Blimber’s dog Diogenes to make treasured memories:

He wanted them to remember him kindly; and he had made it his business even to conciliate a great hoarse shaggy dog, chained up at the back of the house, who had previously been the terror of his life: that even he might miss him when he was no longer there. (Chapter XIV)

Later, Florence is given Diogenes as a pet, in considerate acknowledgement of Paul’s love.

Dickens’s use of animal imagery

Investigation into dog and cat mentions using CLiC reveals Dickens’s animal imagery as altering creatively across his novels for specific artistic and thematic purposes. While Dickens may have loved both animals, their literary use implies an awareness of their different social roles and gendered ownerships in the Victorian age. While he might have preferred to sit by a cat on a quiet evening indoors with family, the faithful intelligence of a canine companion would serve as the more practical choice for a nocturnal evening out and about. Though cats, associated with nurture and domesticity, are referenced more positively overall, it seems that Dickens found more varied inspiration and perhaps even personal identification with dogs in their multiple situations, as treasured pets, wretched waifs and strays, and liberated roamers of city streets.

References

- Dickens, Charles. “Letter To Lady Molesworth,” 20 September 1865. The Charles Dickens Letters Project. Accessed 12 May 2020.

- Dickens, Mamie. Charles Dickens by His Eldest Daughter. Illustrated by C. E. Brock. London: Cassell & Company, 1885.

- Mahlberg, M., Stockwell, P., de Joode, J., Smith, C., & O’Donnell, M. B. (2016). CLiC Dickens: Novel uses of concordances for the integration of corpus stylistics and cognitive poetics. Corpora, 11(3), 433–463.

Illustrations

- “Jerry’s Dancing Dogs.” Illustrated by Hablot Knight Browne. The Old Curiosity Shop (1841). Scanned image and text retrieved from The Charles Dickens Page.

- “Mr. Krook and His Cat.” Illustrated by Harry Furniss. Dickens’s Bleak House, The Charles Dickens Library Edition, 1910. The Victorian Web. Image capture and formatting by George Landow.

- “Charles Dickens’ Cat Extinguishing the Candle.” Illustration by Harrison Weir, 1880 published in Uncle John’s Anecdotes of Animals and Birds by RSPCA and S.W. Courtesy of LJMU Special Collections and Archives.

Further Reading

- Chez, Keridiana. Victorian Dogs, Victorian Men: Affect and Animals in Nineteenth-Century Literature and Culture. Ohio State University Press, 2017.

- Cohn, Elisha. “Dickens’s Talking Dogs: Allegories of Animal Voice in the Victorian Novel.” Victorian Literature and Culture, vol. 47, no. 3, 2019, pp. 541–574.

- Defillipis, Clara. “The Objectionable Dog”: Dog and Master as Metaphor in Little Dorrit.”The Dickens Society blog. 9 June 2017.

- Kean, Hilda. “From Skinned Cats to Angels in Fur: Feline Traces and the Start of the Cat-Human Relationship in Victorian England.” Cahiers Victoriens Et Edouardiens, no. 88 Automne, 2018, pp. 1-13.

- Pyke, Jenny. “Charles Dickens and the Cat Paw Letter Opener.” 19: Interdisciplinary Studies in the Long Nineteenth Century, 01 October 2014, Issue 19, pp.1-7.

- Whitlow, Roger. “Animals and Human Personalities in Dickens’ Novels.” CLA Journal, vol. 19, no. 1, 1975, pp. 65–74. JSTOR.

Suggested citation: Craig, L. (2020, May). “Mew says the cat…Bow-wow-wow says the dog”: Which animal did Dickens prefer? [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2020/05/25/which-animal-did-dickens-prefer/

Enjoyed this post? The Birmingham & Midland Institute has set up a fundraising campaign to “offset the income which would usually keep the BMI running as the social and cultural hub that it should be, and encourage you to donate to what is an important lifeline for many older people in our society.” Check out their fundraiser here.

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?