Theadora Jean is a Gothic scholar and writer. Her novella The Westenra House, a 21st century adaptation of Dracula stripped of the supernatural, based on found text and social media, formed part of her critical-creative PhD from Royal Holloway. She writes melancholy, southeast-London Gothic fiction and non-fiction under the name T.S.J. Harling, her print chapbook, Tower Block Ghost Story, is out with Nightjar Press now. In this blog post she uses the CLiC Web App to explore how Dracula functions as a palimpsest of textual layers and narrative complexities, wherein characters navigate the power dynamics of the written word to assert dominance over the narrative.

Dracula is a novel obsessed with text. Almost every critical discussion of the book acknowledges the multitude of varying textual productions within the book – memorandums, medical reports, personal diaries, tabloid journalism, legal documents and more – because the very format of the novel consists of differing forms of narration, that is, different modes of text. There is no master narrator, omnipotent or otherwise. There is no one hero in Dracula, only the iconic villain, who verbally contributes just a few lines to the novel, welcoming Jonathan Harker to his castle.

A palimpsest traditionally refers to a manuscript where traces of earlier writing are still visible beneath the surface — just as a palimpsest bears visible traces of its earlier forms, Stoker’s novel contains layers of textual interactions and narrative intricacies, each influencing and enriching each other.

Beyond the multiple textual modes in the novel, the characters themselves are constantly preoccupied with both the production of texts, the complication of texts and the desire to assert dominance over narrative. In this blog post, I will be using the CLiC Web App to examine this aspect of the novel to demonstrate that Dracula is a novel consisting of palimpsestual struggle.

The contributors to the text are consumed with the power and importance of writing and the written word. For Dr Seward, the diary entries of the vampire hunters are documented evidence to form a legal case — he believes that ‘perhaps some day this very script may be evidence to come between some of us and a rope.’(356).

When the Count imprisons Jonathan in his castle, his objective is to exert control over him through writing. He seizes Jonathan’s coded letters to his fiancée, Mina, which he destroys and compels him to write according to his own dictation. These manipulated letters are dated ahead of time, which means Jonathan effectively learns his own Death Day, writing in his journal ‘I know now the span of my life. God help me!’ (p49). The opening gambit of the novel is the Count writing over Jonathan’s textual productions, and that process is intended as a fatal one. However, Jonathan responds to this existential threat by defiantly continuing to write, acknowledging in his diary after escaping ‘I must keep writing at every chance, for I dare not stop to think. All, big and little, must go down; perhaps at the end the little things may teach us most.’ (p308)

Mina, an enthusiastic diarist aspiring to write like ‘lady journalists’ (p. 63), influences her privileged friend Lucy, who endeavours to mirror her bourgeois companion. As the Count’s dark influence encroaches upon Lucy, she recognizes the power of Mina’s written record and strives to emulate it, endeavouring to reclaim agency within the narrative by attempting to write herself out of the story that the Count has constructed for her. For when Lucy is in the process of being vamped by the Count, she desperately and heroically turns to her diary to save her friends, even if it is too late for her.

I write this and leave it to be seen, so that no one may by any chance get into trouble through me. This is an exact record of what took place to-night. I feel I am dying of weakness, and have barely strength to write, but it must be done if I die in the doing. (p153)

For Rebecca Pope, in her compelling article ‘Writing and Biting in Dracula’ (2008), writing is a means of marking, like the vampire bite, and ‘it is primarily women who are marked, who receive the impressions of another, usually male, which function as symbols to be read’. The Count writes on the body of Lucy with his bite, as well as Mina, later in the book.

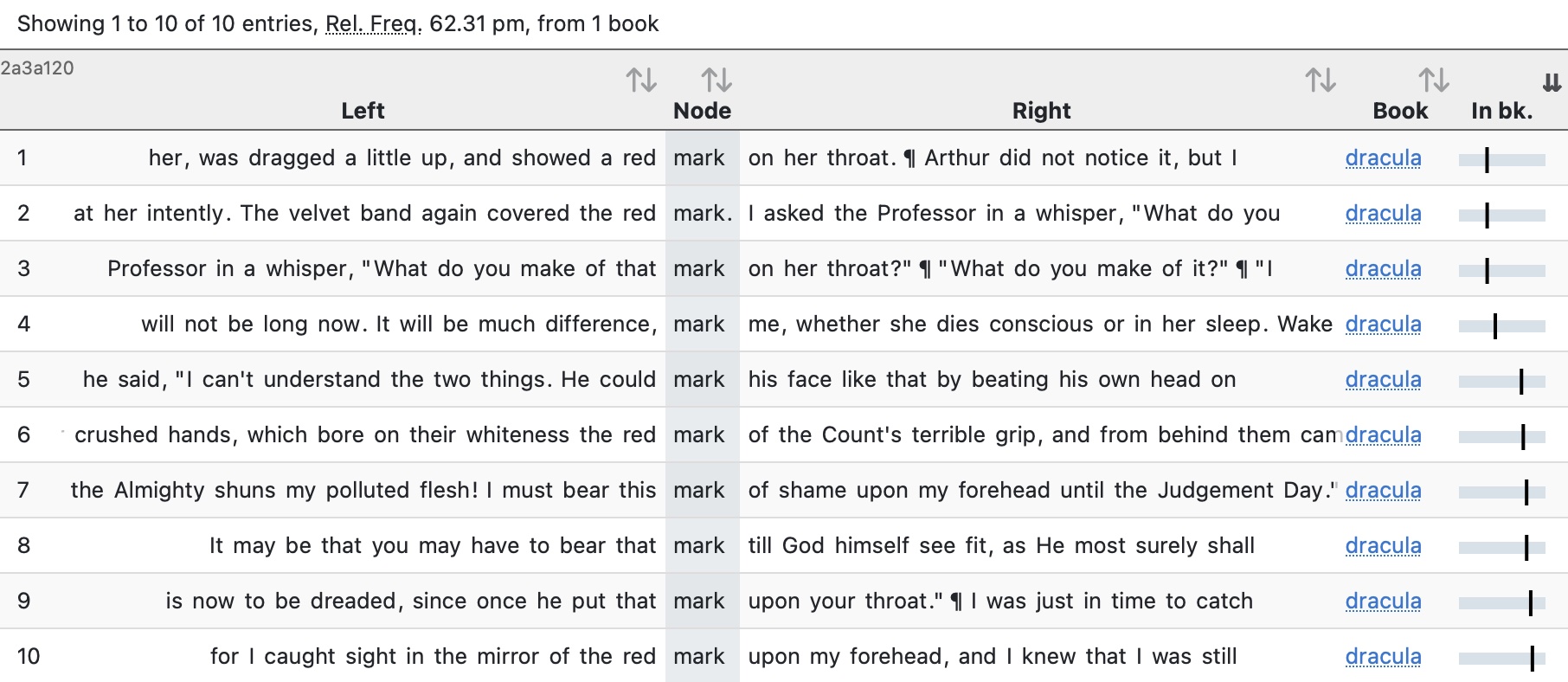

Using the CLiC Web App, I conducted a concordance search for the word ‘mark’ in Dracula. The ten instances of the term ‘mark’ evoke how violent marking is in Dracula. In line 1, Lucy is ‘dragged’ and might ‘die conscious or in her sleep’. In line 5 the vampire hunters speculate that the mentally ill in-patient of Dr Seward, Renfield, has marked himself ‘by beating his own head’ after an encounter with the Count. Mina’s ‘poor crushed hands’ in line 6 bear ‘the terrible mark of the Count’s terrible grip.’ Lines 7 and 10 refer to the mark inflicted by the Count on her forehead, a mark which cannot be hidden — representing the corruption of the vampire on her body and soul.

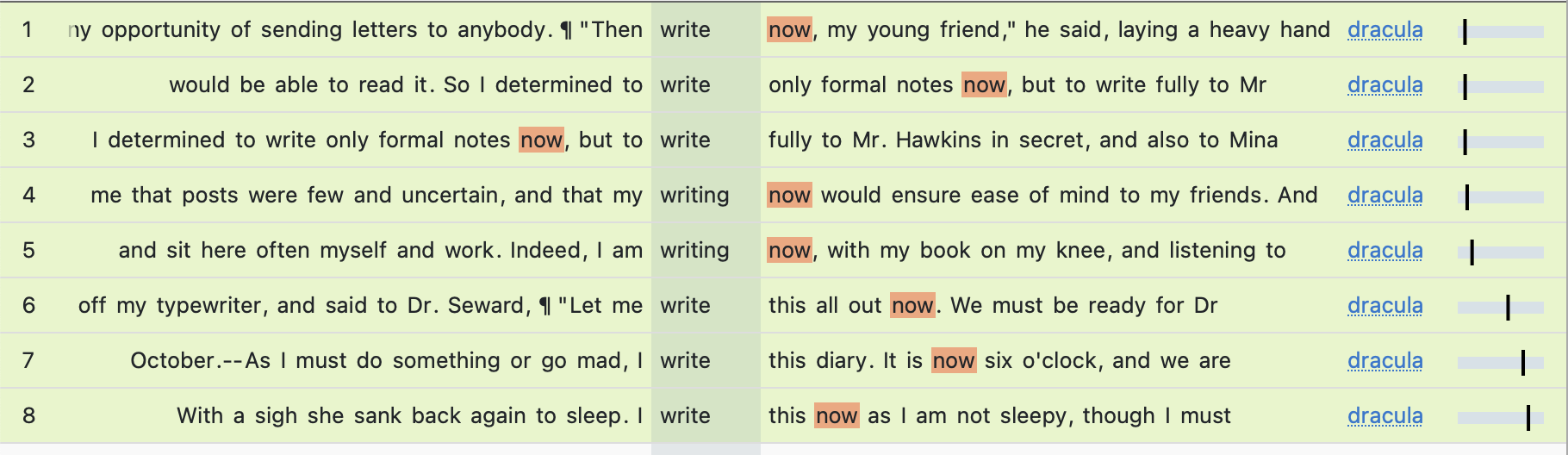

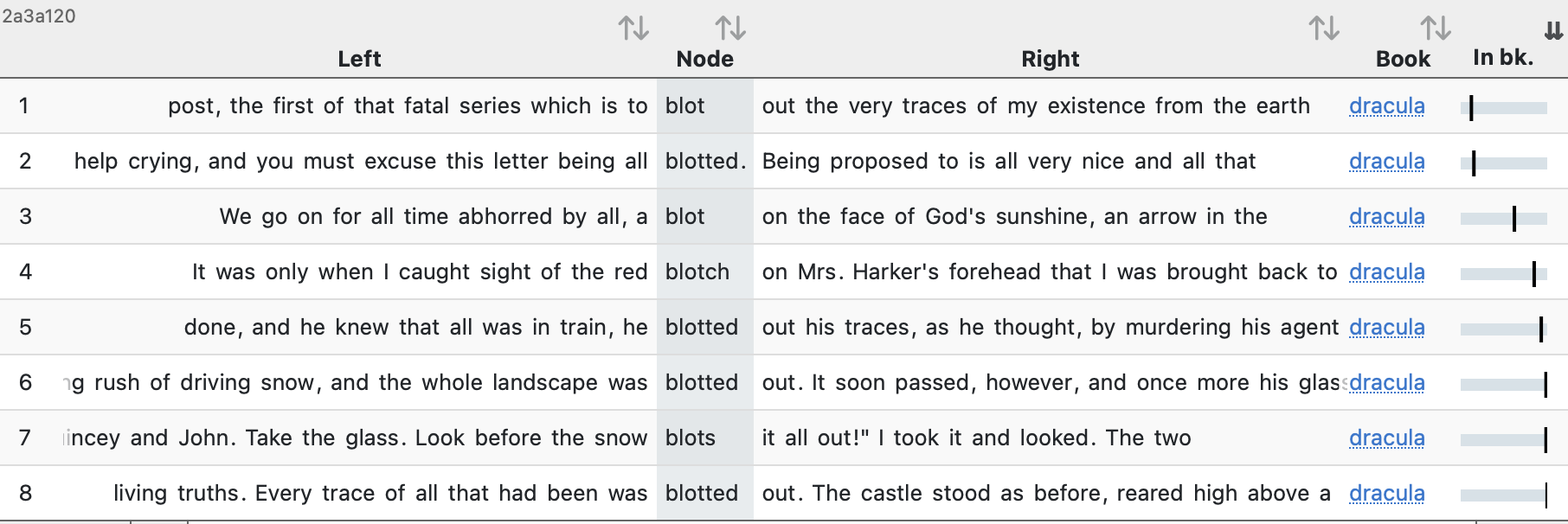

Writing has much urgency here, as it is the site to regain control over the vampire bitemark. Using CLiC’s concordance feature, I conducted a search for ‘writ*’ to identify examples of writing in Dracula, using an asterisk (indicating a wildcard) to capture variations such as ‘write, ‘writing,’ ‘written,’ etc. I then used the KWICGrouper to look for occurrences where the word ‘now’ appeared adjacent to writing indicating a sense of immediacy in the narrative. This analysis revealed eight occurrences where variations of ‘writing’ were accompanied by ‘now,’ intensifying the energy and action of the novel. Moreover, it expresses the power of the palimpsest, that writing over the enemy is of utmost importance.

Notably, ‘record*’ appears in the text 26 times. This underscores the vampire hunters’ desperation to secure an ‘exact record’ of events, reflecting their deep anxiety and preoccupation with documenting their experiences. The concept of their textual productions gives them deep anxiety – they don’t just write about the Count they write about writing about him.

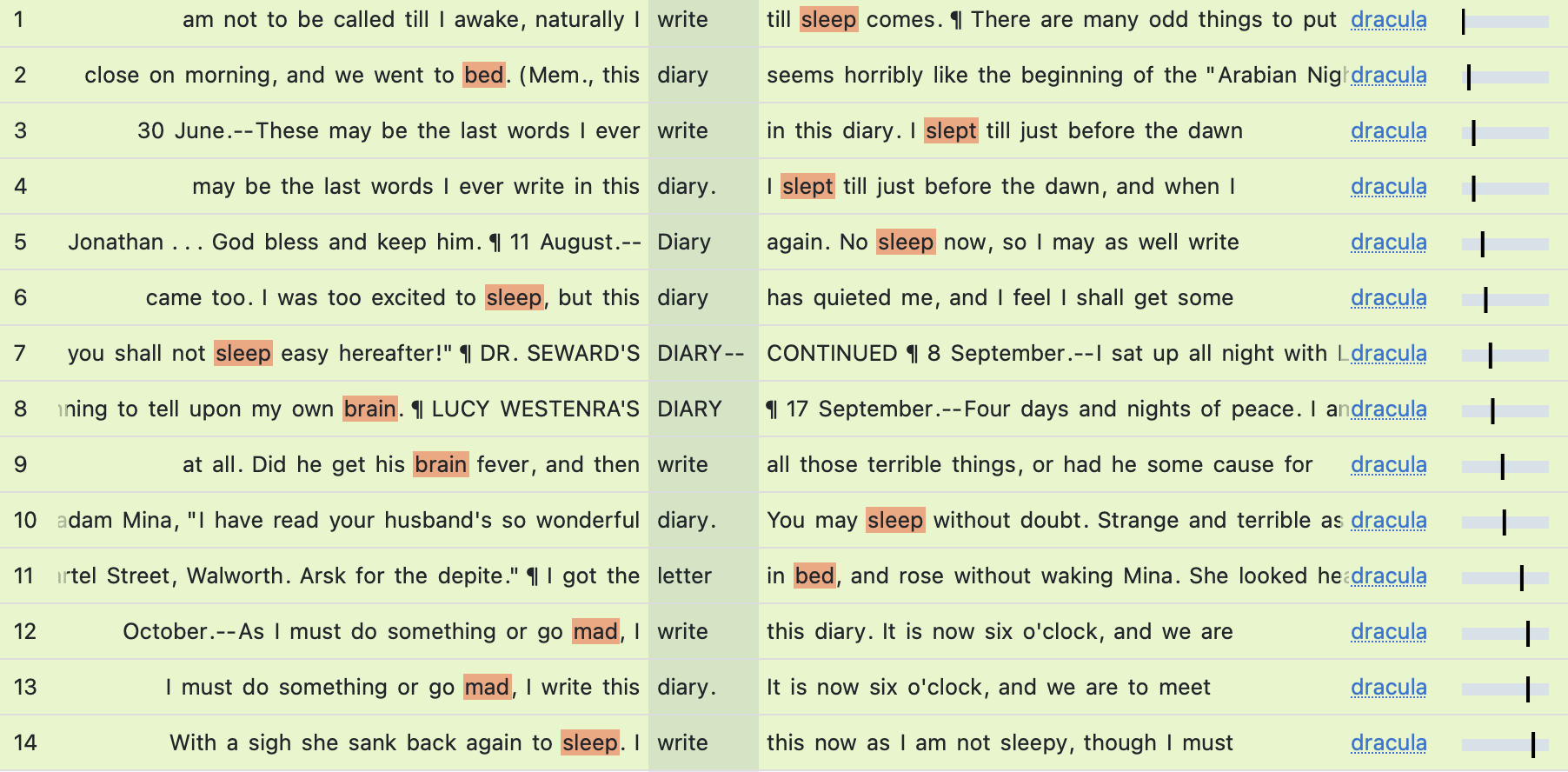

Despite the characters’ quest for accuracy and authenticity, further analysis reveals a challenge to their belief that text can offer an ‘exact record’. Running a concordance search for both ‘letter*’, ‘diar*’ and ‘writ*’ (and selecting the ´any word´ option) a pattern emerges in which writing is intimately associated with sleep, madness and dreams (see figure 5).

Further examination of terms used to discuss textual production provokes questions about the meaning of the novel itself. In the climactic finale of the narrative the Count dies, having been overcome by the group of vampire hunters who ‘mark’ him by stabbing him with a knife. This event underscores the notion that text is a battleground in Dracula, as the hunters succeed in ensuring that the mark of the vampire is erased — the ‘red blotch’ upon Mina’s forehead vanishes forever after the Count has been vanquished. In the conclusion of the novel, Jonathan notes that ‘every trace of all that had been was blotted out’ (p402). Jonathan has his revenge on the Count who wrote over him and tried to designate his Death Day by marking him, and it is his wife, Mina, who writes up the Count’s Death Day in her own diary (dated the 6th November). The polyphonic narration of the novel is determined by the vampire hunters, those who were once written over, and marked. Through their collective efforts, they seize control of the narrative by constructing a new body of evidence — the series of documents that make up the novel itself. In doing so, they effectively overwrite the mark of the vampire, triumphantly reclaiming agency and reshaping the course of events. Thus, the work of fiction we have known as Dracula emerges as a palimpsest, with the victory of the vampire hunters imprinted on its pages.

References

Pope, R. A. (1990). Writing and biting in Dracula. Lit: Literature Interpretation Theory, 1(3), 199–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/10436929008580030

Please cite this post as follows: Jean, T. (2024) ‘Nothing but a Mass of Typewriting’: Dracula as Palimpsest [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from [https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2024/03/21/dracula-writing]

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?