In the anniversary week of Charles Dickens’s death, 150 years ago, we are delighted to present you a personal view of Charles Dickens by his great great grandson Gerald Dickens (@DickensShows on Twitter). This post is brought to you as part of the BMI Lockdown Life initiative, in collaboration with the Birmingham & Midland Institute. Join the conversation on Twitter with #BMILockdownLife.

Welcome to a short series of blog posts about the art of adapting the works of Charles Dickens for theatrical performance. I hope that you enjoy them.

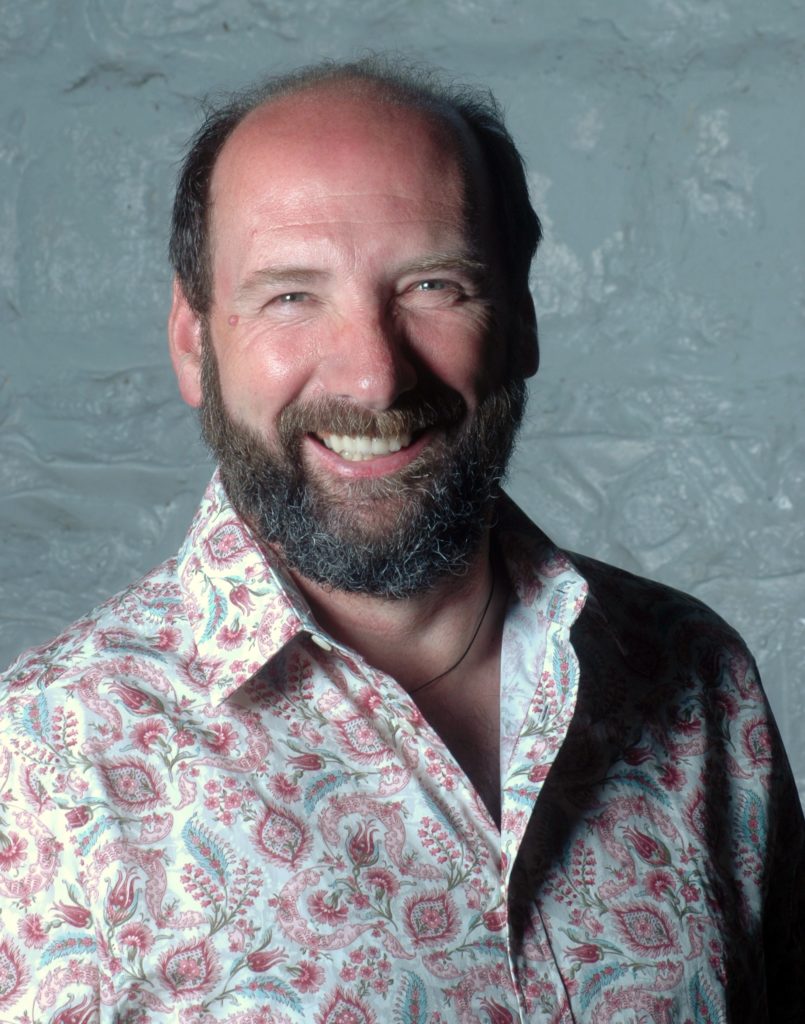

It is my great honour to have been born with the surname Dickens. To fully introduce myself my name is Gerald Dickens, the fourth child of David Dickens who in turn was the third son of Admiral Sir Gerald Dickens. Gerald was the second child to Henry Fielding Dickens, the eighth child of Charles John Huffam Dickens.

The Dickens gene is strong through the family, both physically (I have inherited the family hairline, unfortunately), as is the desire to communicate, educate and entertain. Within our numbers there are many who have turned to journalism, marketing, PR, hospitality and, in my own case, the theatre which was of course a particular love of Charles himself.

Warming up to Charles Dickens’s characters

Up to the age of thirty my theatrical career was spent mainly in the world of corporate entertainment and training, as well as appearing in a few repertory productions and even directing and producing a little, but there was no real shape or direction to my professional life, however that all changed with a phone call in May of 1993 from an enterprising lady who was responsible for raising money for a local charity. December 1993 would mark the 150th anniversary of A Christmas Carol being published, she reminded me, and there was to be a lot of publicity to mark the event. I was an actor. I was related to Charles Dickens. He was an actor. She needed a high-profile event to raise funds. Why didn’t we join forces and recreate one of the lavish public readings for which ‘The Inimitable’ was so well known? To be honest I wasn’t keen as I had shrunk away from the works of my great great grandfather after being tormented by Oliver Twist during my “O” level English classes at school. My coolness had thawed a little in 1980 when the family were invited en masse to watch the Royal Shakespeare Company’s epic eight-hour production of Nicholas Nickleby. I was astounded by the sheer theatricality not only of the performance but the plot itself. The following week I sat down to re-read Oliver Twist and then embarked upon Nickleby. In both cases I discovered not the never-ending dirgy novels that I had expected but exciting, character-filled scripts which rushed from scene to scene as a modern screenplay might do. My epiphany had begun but it would need a much more intimate connection with the words of Charles Dickens to be completed.

Dickensian advice

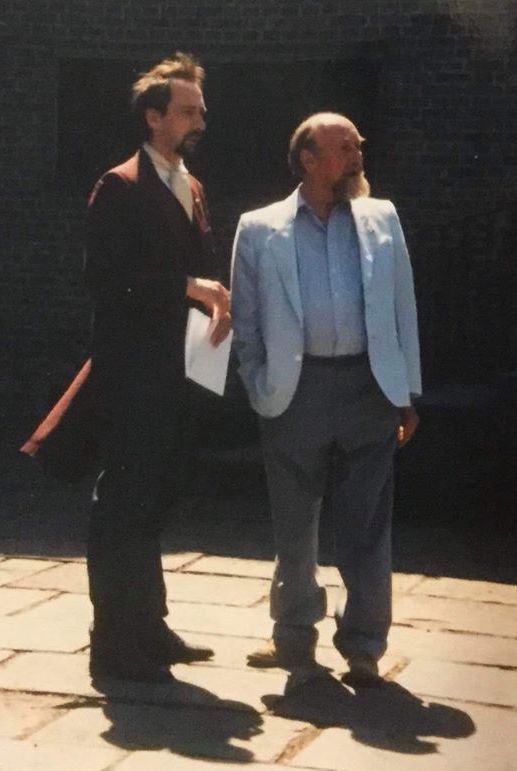

As 1993 moved on I rather put the invitation to perform a Christmas Carol to the back of my mind until it was brought back to me in November with another call reminding me that the event was coming up soon and was everything ok? I panicked a little, realising I had no knowledge of Dickens’s reading career, or how to hold an audience’s attention for almost two hours. I decided to approach the finest Dickensian mind I could think of for advice; the individual in question was a huge fan of the author as well as a superbly read scholar: my Dad.

My father had superbly restrained himself over the years by not forcing his love of Dickens onto his children. He encouraged us all to follow our dreams and passion, to do whatever we wanted to do with verve and enthusiasm, and above all to do it to the very best of our abilities. He supported us and gave us advice when it was needed. He loved theatre and was very proud that he had once played Portia in his school’s production of The Merchant of Venice, his carefully marked script was one of his proudest possessions. His happy memories of treading the boards meant that he often accompanied me to rehearsals for the plays I was involved in as a boy and during one such when I was gabbling my lines to an extent that nobody could hear what I was actually saying, he took me aside and gave me a piece of advice that any top drama school would have been proud of, he simply said “always finish one word before you begin the next one.” Brilliant!

When I approached him in ’93, his excitement that I was moving into the world of Dickens was palpable, indeed he almost exploded with enthusiasm. He told me all about the Dickens readings, how ladies had fainted with the emotion of the performance, he showed me pictures of Charles Dickens at his reading desk (we would need to build one of those), he told me which biographies to read, and most importantly he gave me a copy of the actual script that Charles Dickens had created for his performances. Having done all that my dad went on to do the best thing that he could have possibly done: he left me to create my own show. Before I was let loose however he gave me one enigmatic piece of advice which would become central to the performance:

“Remember,” he said, “that Dickens has done all of the work for you”.

At home I set up the script on a stand to replicate the original desk and began reading. “MARLEY was dead: to begin with. …”. It was important to me to put my own mark on the show, so I had decided to use my vocal and physical talents to bring each of the characters to life, but how would I create each one? Where would their personalities spring from?

I read on and arrived at the first description of Ebenezer Scrooge:

Oh! But he was a tight-fisted hand at the grind-stone, Scrooge! a squeezing, wrenching, grasping, scraping, clutching, covetous, old sinner! Hard and sharp as flint, from which no steel had ever struck out generous fire; secret, and self-contained, and solitary as an oyster. The cold within him froze his old features, nipped his pointed nose, shrivelled his cheek, stiffened his gait; made his eyes red, his thin lips blue; and spoke out shrewdly in his grating voice. (Stave I)

By the end of the paragraph I had transformed into Scrooge: my body was contorted, my face was shrivelled, my hands were arthritic and claw-like, whilst from my mouth came a harsh biting voice. As an actor I had done nothing specific but, as my father had so shrewdly pointed out, Dickens had done the work for me.

Discovering the joy of performing Dickens

In that short period of rehearsal, I discovered the joy of performing Dickens. Each of the characters had been endowed with a complete personality which is introduced to the modern reader from the moment we learn their names, for example how could Mr Fezziwig be anything but cheerful and generous of spirit? During my preparation I found a distinct voice for each individual: Bob Cratchit became a softly spoken clerk from Cornwall because the gentle lilt contrasted nicely with the bark of Ebenezer, thereby permitting a rapid-fire conversation between the two without the need for sundry confirmations as to who is speaking. The charity collector who solicits Scrooge on Christmas Eve was based on Margaret Thatcher’s head-tilting “we are a grandmother” announcement, whilst The Ghost of Christmas Present was a bluff, hearty Yorkshire giant. Everything fell perfectly into place to the extent that I am still performing the piece 27 years later and the voices haven’t changed at all.

My first foray into the world of performing Charles Dickens was an exciting one and opened up a whole new ocean of experience for me to swim in. In the intervening years I have performed many of the readings that Charles prepared for his own repertoire and every time I settle down to begin my preparation I remember and follow the advice of my father: “Dickens has done all of the work for you.” It is advice that has served me well.

In my next post I will go into more detail about Charles’ own performing career and continue the story of my own.

Suggested citation: Dickens, G. (2020, June). Bringing Dickens to the Stage. Part One: A Christmas Carol. [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog. https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2020/06/10/bringing-dickens-to-the-stage-part-one:-a-christmas-carol/

Enjoyed this post? The Birmingham & Midland Institute has set up a fundraising campaign to “offset the income which would usually keep the BMI running as the social and cultural hub that it should be, and encourage you to donate to what is an important lifeline for many older people in our society.” Check out their fundraiser here.

I believe in each performance Dickens takes over your very body and soul. I know. I have seen it happen twice at Christmas time in Minneapolis. I only wish you would come here again so I could bring this Christmas gift to my grandchildren. At the conclusion of your performance it suddenly truly feels like Christmas.

I very much enjoyed this history of how Dickens came to be of such importance to you as he always was to your father. Your father sounds very wise. I look forward to continuing to read and enjoy your informative blogs.