Nat Reeve is a novelist and AHRC-funded PhD candidate at Royal Holloway, University of London. Their debut novel, Nettleblack, is out June 23rd 2022 with Cipher Press, with a sequel forthcoming in 2023. Nat’s PhD project is a queer reading of Elizabeth Siddal’s art and poetry, featuring unruly Books of Hours, tree-person hybrids, sapphic musicians and horrible geese. They were the 2020 Amy P. Goldman Pre-Raphaelite Fellow at the University of Delaware and Delaware Art Museum, and have academic publications forthcoming in Word & Image and Pre-Raphaelite Sisters: Art, Poetry and Female Agency in Victorian Britain, edited by Glenda Youde and Robert Wilkes.

It feels delightfully surreal to begin thus, but the title of this post quotes from my novel – Nettleblack, my queer Neo-Victorian debut, springing forth on June 23rd with Cipher Press. I’ll set that quote in context to lead us into this blog post, which ponders the first-person journal form, as explored by Wilkie Collins and I, by way of the CLiC Web App (Mahlberg et al. 2020).

The quote’s narrator (I ought to say writer; it’s her journal) is anxious Welsh heir/ess Henry Nettleblack. She’s tentatively nonbinary, immensely sapphic, about to run away to escape the looming threat of marriage, and reflecting on her inability to stand up for herself:

This journal, I ought to specify, is in no way representative of my capacity to engage in any manner of verbal sparring – or verbal pleading – or indeed verbal conversation in all of its variants. The world has never received even a sentence of the gumption I write with. I’m far too indelibly sealed in everyone’s minds as a spineless child with incongruously excellent cravats. Not that I intend to let my ineloquence win again in this instance. (Reeve 7)

Henry’s not wrong (mostly). She’s ill-equipped for ‘verbal sparring’ – a stammer, social anxiety and being read as a marriageable young Victorian lady will do that to you. ‘Verbal pleading’ is out too – all the enforced gender roles in ‘the world’ can’t make her better at soft words and helpmeet eyes. But ‘verbal conversation’ is an interesting one. Though she struggles with it in practice, most of the ‘verbal conversation’ in the novel is conveyed via the lens of her journal, hemmed with her editorial thoughts. She chooses which aspects of ‘the world’ get the focus and the platform – as in this deliciously spoiler-free example, where she purposefully blanks a roomful of reactions to focus on the bicycling butch* she’s infatuated with:

I’ve not the faintest what Mr. Adelstein’s orderly face did. I’ve not the faintest whether Nick held his rats, or dropped his rats, or dipped in to nod his agreement. There was quite one thing in my known world, and it was Septimus’s expression. (76)

‘The world’ – too broad, too liable to make the wrong assumptions – has become ‘my known world’, a zooming-in that lets the ‘spineless child’ claim agency at last. The journal form enables, protects, and foregrounds this shift.

Nettleblack evokes the sensational epistolary fiction of the nineteenth century, and Wilkie Collins – one of the many stars in CLiC’s firmament – is a guiding luminary. My novel, following a similar modus operandi to Collins’s The Moonstone (1868) and The Woman in White (1859), sets Henry in a chaotic network of narrators, all of whom are aware of themselves as people writing their own perspectives. Henry, like The Woman in White’s frustrated onlooker Marian Halcombe, combats a straitened social position (for Marian, helplessness in the face of Sir Percival’s scheming) with the power of scribbling in a journal. As with every writing receptacle in Nettleblack, Marian’s journal becomes an embodied resource in Collins’s fictional world; she can refer back to ‘the regularity of the entries’ and ‘the reliability of [her] recollection’ to assuage ‘the perilous uncertainty’ of her and Laura’s plight. Henry’s journalised ‘gumption’ similarly informs the story – but I shan’t say more, because that would be a spoiler.

My own blazing reread through ‘the regularity of the entries’ in Nettleblack (while checking the proof) brought the implications of the form to the forefront of my mind, as well as its potential receptivity to a corpus linguistics mode of analysis. Though I was meant to be fixing my weird authorial tics, it got me thinking – not about my writing habits, but those of my characters. As in The Moonstone, the story of Nettleblack is told ‘in turn – as far as [each narrator’s] personal experience extends’, and thus every part of it is written in first person. The Neo-Victorian first person can be a reparative strategy, as Emma Catan has shown, ‘challeng[ing]’ the ‘silencing effect’ third person can have in depictions of marginalised identities, and ‘restor[ing] agency to non-normative characters’. As my first example shows, the form doesn’t just give ‘non-normative characters’ a (written) voice – it lets them take it for themselves.

That’s all the more important when almost every Nettleblack narrator is very, very queer. This is part of why I’m drawn to Marian, and to The Moonstone’s Ezra Jennings. These two characters, who solve everything with intense journal entries, are immensely queer and have been frequently read as such. In Queer Others in Victorian Gothic, Ardel Haefele-Thomas sees Marian and Ezra as demonstrating ‘that queer people […] can have a crucial role in society’, albeit one which does not have the ‘privilege of working completely outside the bounds of heteronormative social structures’ (Haefele-Thomas 12). Marian and Ezra, ‘exist[ing] on the margins’, can ‘see beyond the facades of “normal” and “reality” and instead perceive less conventional underlying truths’ – and then spoon-feed those ‘truths’ (literally, in Ezra’s case) to their flailing cis-heteronormative companions (11-12).

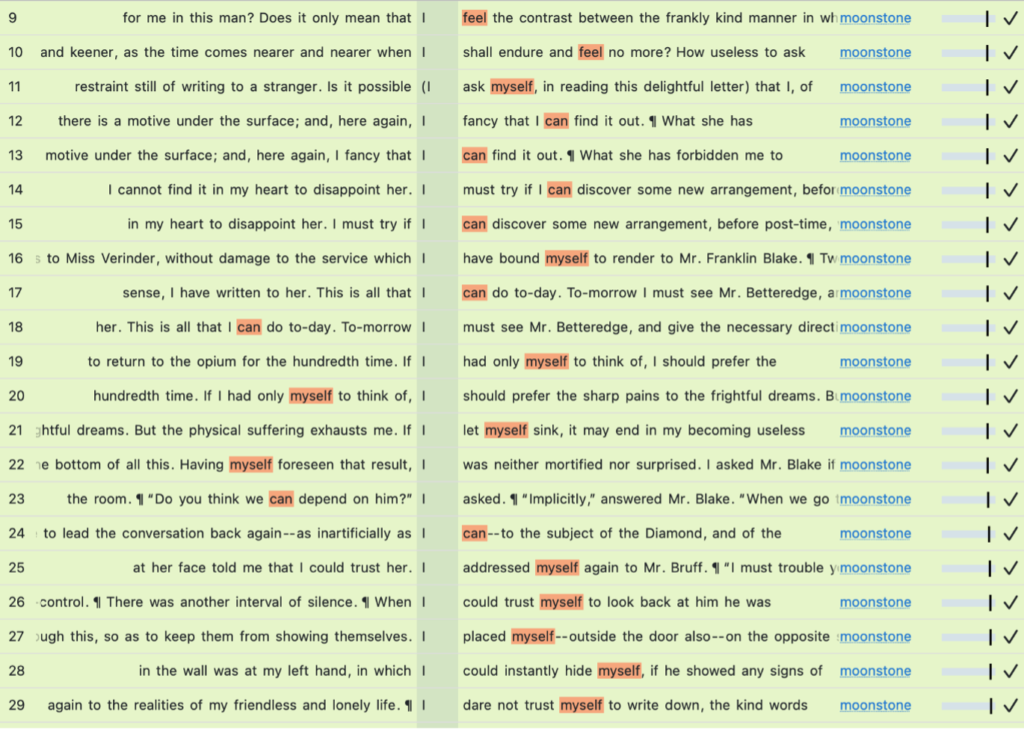

Ezra is well-suited to ‘perceiv[ing] less conventional underlying truths’. Highly concentrated observation and self-reflection, enabled by the form, is very much his modus operandi — if you look at where ‘I’ appears (and what it’s surrounded by) in his journal. A concordance search on CLiC for ‘I’ in The Moonstone brings out moments of critical introspection that are linguistically signposted (Fig. 2). To get at this, I limited my subset to ‘non-quotes’ to exclude dialogue, avoided the other ten narrators by filtering the concordance lines by their location in the novel (‘in bk.’ on the upper right of the screen), and ‘tagged’ the lines included with Ezra’s journal as ‘Ezra’. Then I used the KWICGrouper to highlight words that collocate with ‘I’ within a given span – in this case, ‘can’, ‘feel’, ‘myself’ and ‘think’:

Haefele-Thomas observes that, unlike The Moonstone’s other first-person contributions, Ezra’s journal is not written after the event to fit the compiler’s heteronormative wishes. Though Ezra serves the marriage plot, he writes to and for himself. You can see this perspective in line 11 of figure 2 (‘I ask myself’) – and in instances where ‘I’ appears twice in quick succession as in lines 12, 13, 14, 15, 19 and 20 (‘I think I’, ‘I fancy that I’ etc.). Ezra’s journal may play a ‘crucial role in society’ in retrospect, but his immediate writerly ruminations are their own society, a prism of multiple ‘I’s which ‘find […] out’ answers. Though his interactions with ‘the world’ he describes are (like Henry’s) repeatedly met with scorn and hostility, the insightful potential of his writerly agency is resolutely apparent.

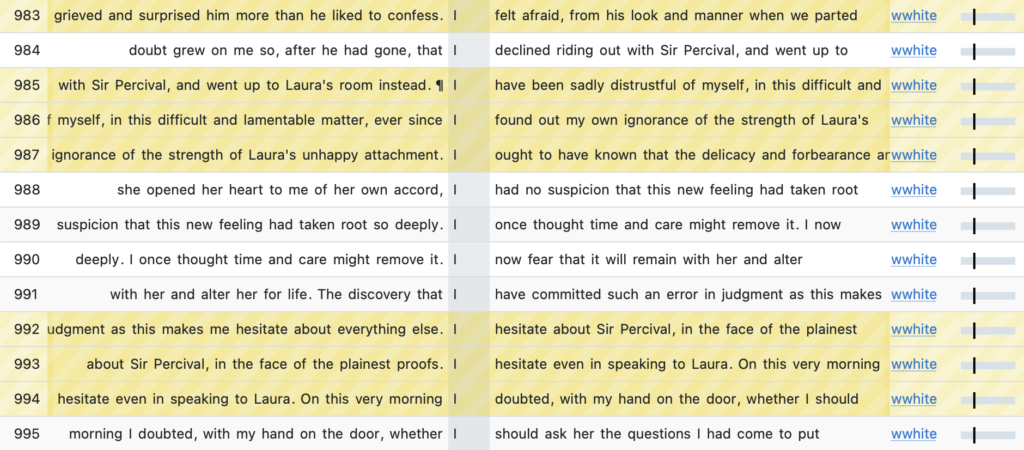

Exploring the same idea with Marian’s journal in Collins’s The Woman in White reveals a surprising parallel between her self-representation and the Nettleblack quote I started with. Marian Halcombe and Henry Nettleblack are ostensibly not much alike: Marian’s practical, self-assured and an excellent conversationalist, whilst Henry is chaotic, inarticulate, terrified of everything and utterly devoid of self-esteem. Returning to Marian’s journal via the CLiC Web App, I expected this contrast to shine forth. But here’s what happens when you start scrolling through Marian’s ‘I’s:

Though other narrators portray Marian as a no-nonsense font of wisdom, Marian’s writing tells a different story, one far more akin to Henry’s. Like Henry, Marian’s journal starts in the immediate aftermath of a major social setback – in Marian’s case, not realising how attached Walter and Laura have become. Marian’s writing offers another collision of agency (holding the pen, guiding the perspective) and panic. ‘I felt afraid’ begins the journal with unabashed vulnerability; ‘I hesitate’ appears repeatedly; other results foreground Henry-esque self-reproach (‘I have been sadly distrustful of myself’, ‘I found out my own ignorance’, ‘I ought to have known’, ‘I doubted’). The version of Marian ‘indelibly sealed in everyone’s minds’ by Walter Hartright’s voyeuristic gawping is as remote from the character’s written self-expression as Henry’s social ‘ineloquence’ and scribbled ‘gumption’.

The first-person journal form lets Collins – like me – play with paradoxes, in which an anxious marginalised character can claim a voice on their own terms, without having to give up their depth and complexity to ‘the world’’s inaccurate perceptions of them as a ‘spineless child’ or unshakeable idol. In the laborious endeavour of correcting ‘the world’ when it gets you wrong, as Marian, Ezra and Henry are very much aware, a bit of first-person journalising is an invaluable strategy.

I’m very grateful to Dr Rosalind White for inviting me to contribute to the CLiC Blog, and for coaxing me into the possibilities of digital humanities.

And if you, sweet reader, are inclined to discover more, Nettleblack is available to order from Cipher Press’s website here.

References

* Butch is a type of queer identity that is explained in more detail here.

- Catan, Emma. ‘Challenging Cis-Heteronormativity in The Night Brother’, Alluvium (6 September 2021), https://www.alluvium-journal.org/2021/09/06/challenging-cis-heteronormativity-in-the-night-brother/ [accessed 6 June 2022].

- Mahlberg, M., Stockwell, P., Wiegand, V. and Lentin, J. (2020) CLiC 2.1. Corpus Linguistics in Context, Available at: https://clic.bham.ac.uk/ [accessed 6 June 2022]

- Haefele-Thomas, Ardel. Queer Others in Victorian Gothic: Transgressing Monstrosity. University of Wales Press, 2012.

- Reeve, Nat. Nettleblack, Cipher Press, 2022.

- Wilkie Collins’s The Moonstone and The Woman in White were both accessed via the CLiC Web App.

Please cite this post as follows: Reeve, N. (2022) ‘The Gumption I Write With’: The Chaotic Journals of (Neo)Victorian Characters [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from [https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2022/06/09/chaoticjournals/]

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?