Anya Eastman is a second-year Technê PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London. Anya’s work explores the memorialisation of Charles Dickens, George Eliot and Oscar Wilde, with an emphasis on heritage and material culture. In addition to her doctoral research Anya is the co-director of Royal Holloway’s Centre for Victorian Studies and she has been on placement at the Charles Dickens Museum, working as a research assistant on the upcoming exhibition ‘To be Read at Dusk: Dickens, Ghosts and the Supernatural’. In this post, Anya explores Dickens’s ghosts using the CLiC corpora and discusses her findings alongside plans for the museum’s exhibition.

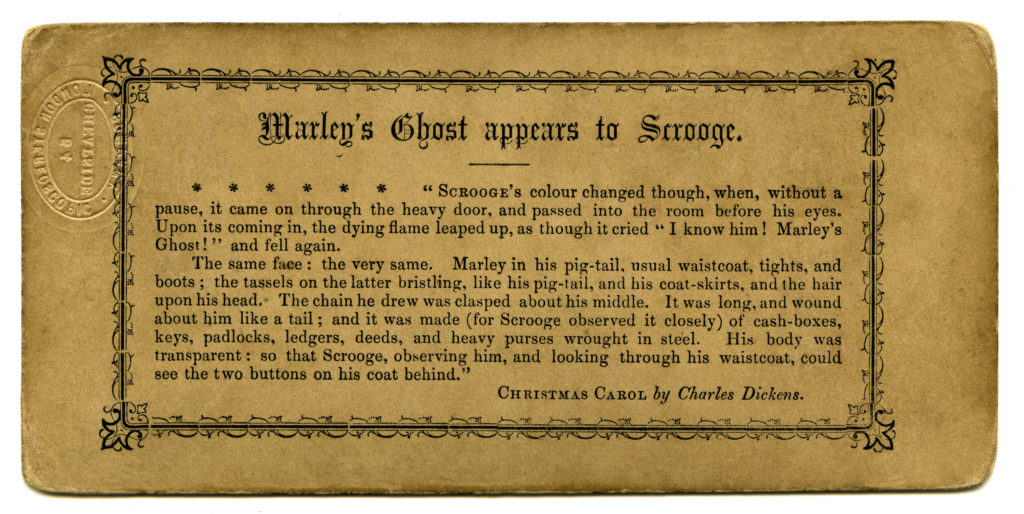

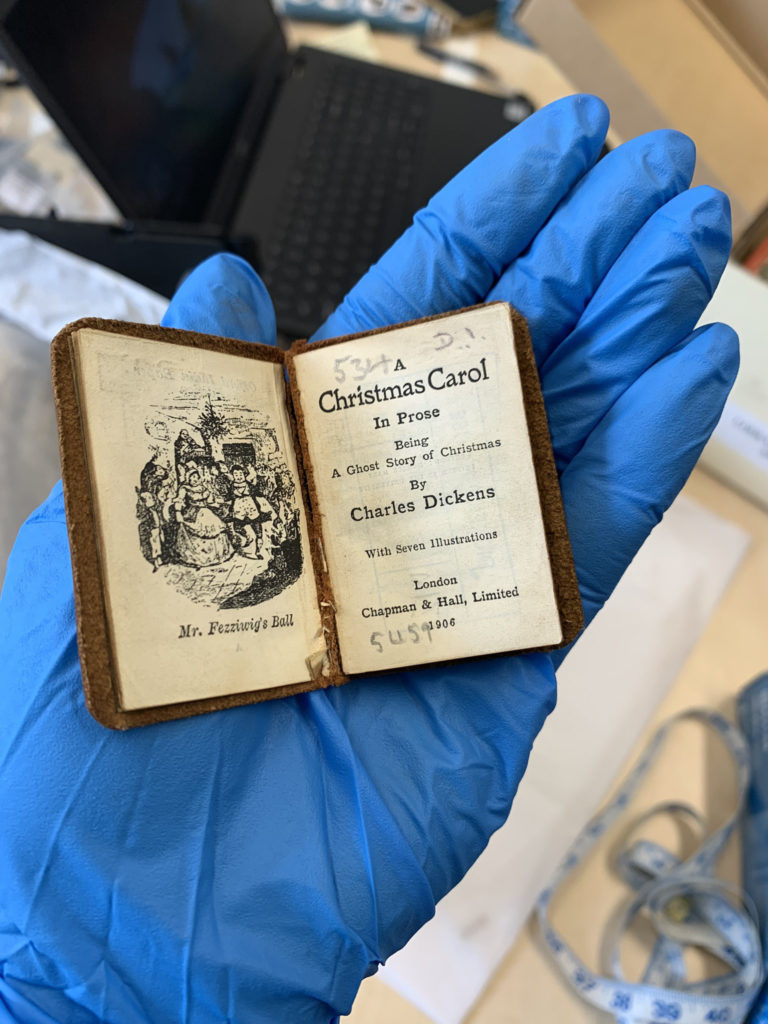

Dickens’s ghost stories have formed a key component of his legacy as a writer, with A Christmas Carol (in its variety of forms: novella, Scrooge, or the Muppets’s adaptation) often serving as an introduction to Dickens’ oeuvre. Today, A Christmas Carol (1843) is on the national curriculum as a GCSE text and, in 2015, the popular video game Assassins Creed included Dickens as a character whose role it was to roam around Victorian London hunting ghosts. In the course of my time working at the Charles Dickens Museum as a Research Assistant on the upcoming exhibition ‘To Be Read at Dusk: Dickens, Ghosts and the Supernatural’, I turned to the CLiC Web App (Mahlberg et al 2020) for an overview of how ghosts figure in Dickens’s corpus. In particular, I sought to ascertain what the relationship was between Dickens’s references to the supernatural, and those of his contemporaries.

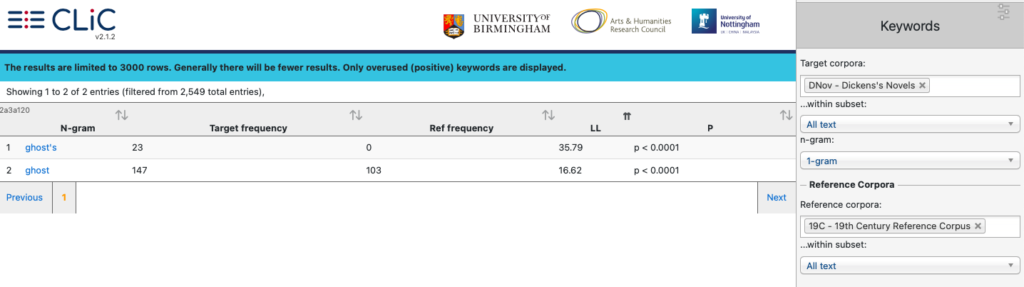

I started by running a keyword test for ghost in Dickens’s novels against the Nineteenth-Century Reference Corpus, allowing me to get a sense of the frequency with which Dickens was referring to ghosts in comparison to his contemporaries. It is important to note that CLiC does not currently include Dickens’s short stories, the form that the majority of his ghost stories take, so the results offered by CLiC are only representative of Dickens’s novels.

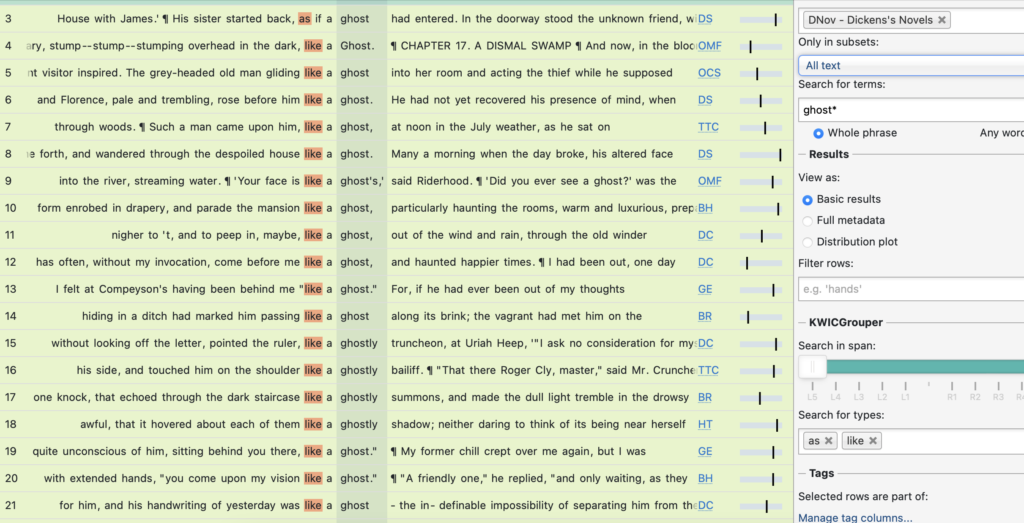

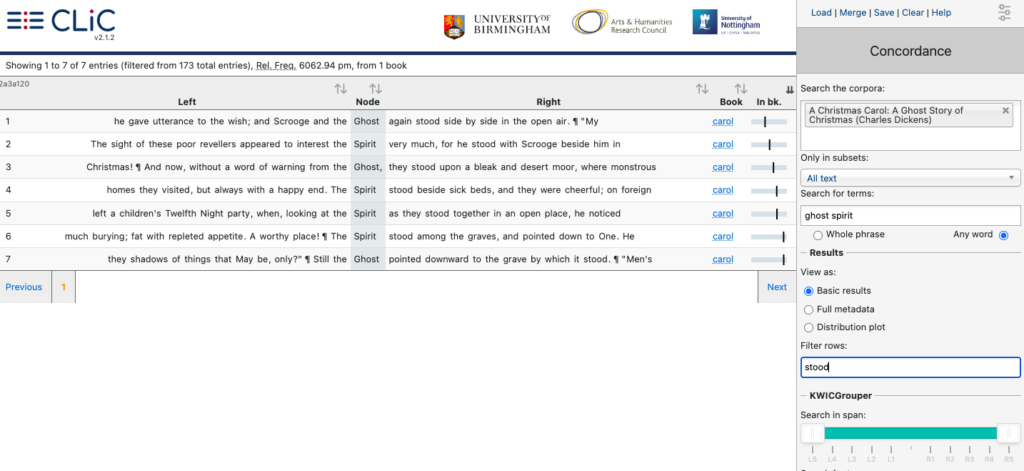

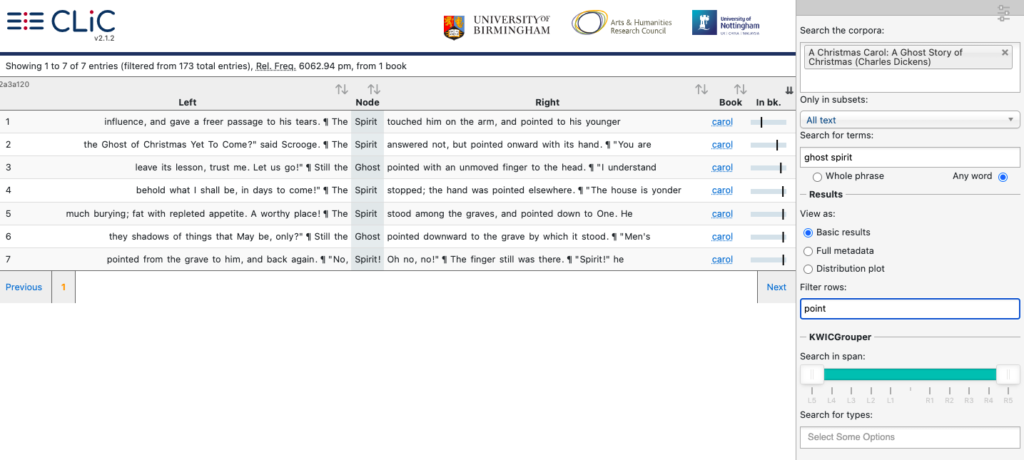

In the novels there are less ‘real’ ghosts, but there are many ghostly spaces and characters. To restrict my search to examples of ghost-like things, I filtered figurative language by using the KWICGrouper to search for ‘like’ or ‘as’ (figure 4).

In the CLiC Nineteenth-Century Reference Corpus, there are three novels by Wilkie Collins and three by Gaskell. This is not to say that there is a direct relationship between ‘The Haunted House’ and the results for ‘ghost’ in the Reference Corpus, but the LL test results show that Dickens is referring to ghosts at a marginally increased rate to his contemporaries, speaking to Dickens’s role in the ghost story genre as both writer and influencer.

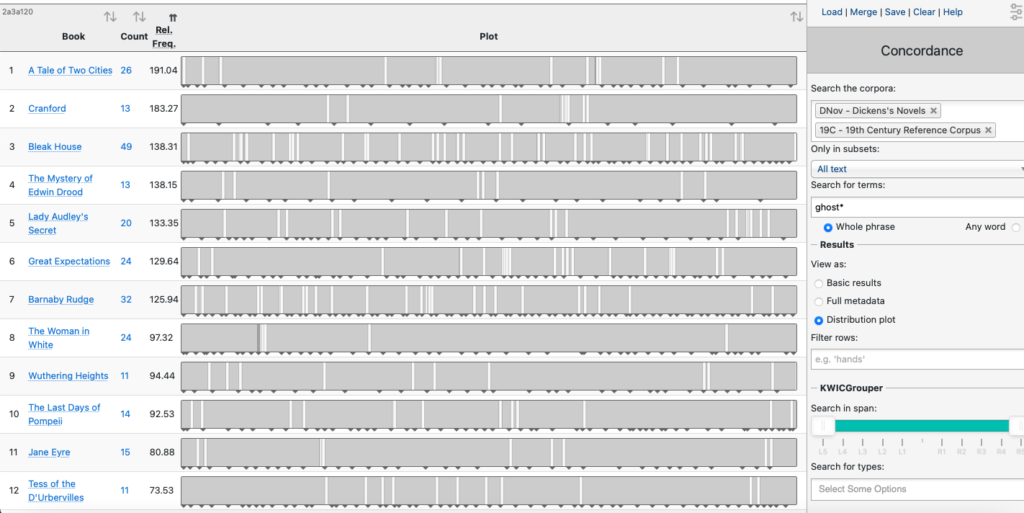

If we compare the distribution of ghost* (the asterisk means that the search will include ghosts and ghostly as well as ghost) across Dickens’s novels, Bleak House (1852), Barnaby Rudge (1841) and A Tale of Two Cities (1859) appear to have the highest concordance count. Bleak House is an unsurprising result, with the ‘Ghost’s Walk’, the ‘ghostly likeness’ of the past and present Dedlocks and the ‘ghostly stories’ that ‘shall be told of the stain upon the floor’ following Mr Tulkinghorn’s murder.

However, if the results are ordered by ‘Relative Frequency’ rather than ‘Count’ (which takes into account the word count of each novel), A Tale of Two Cities moves up to first place, Barnaby Rudge drops from second to fourth, and The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870) moves from thirteenth to third.

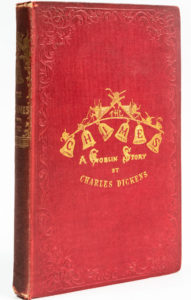

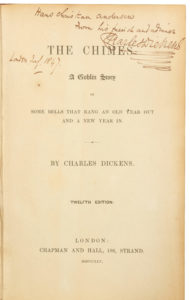

Interestingly, the concordance lines generated for A Tale of Two Cities are mostly referring to an actual ‘ghost’, as opposed to something ghost-like or ghostly. Dickens writes of the ‘Cock-lane ghost’ which ‘had been laid only a round dozen of years, after rapping out its messages, as the spirits of this very year last past (supernaturally deficient in originality) rapped out theirs.’ The inclusion of the ‘Cock-lane ghost’ allows Dickens to — somewhat comically — fictionalise supernatural communication. The Dickens Museum exhibition ‘To Be Read at Dusk: Dickens, Ghosts and the Supernatural’ will explore Dickens’s own feelings about the possibility of tapping into ghostly messages, at a time of huge public interest for séances and spiritualism. This specific reference to a ghost in A Tale of Two Cities provides a fantastic link between Dickens’s fiction and our theories about Dickens’s own thoughts on ghostly rappings.

We can compare these findings again to the reference corpus. When ordered by relative frequency, A Tale of Two Cities still has the highest concordance count, very closely followed by Elizabeth Gaskell’s Cranford (1853), which first appeared as instalments in Household Words. Gaskell writes:

Miss Pole was slightly sceptical, and inclined to think there might be a scientific solution found for even the proceedings of the Witch of Endor. Mrs Forrester believed everything, from ghosts to death-watches. Miss Matty ranged between the two — always convinced by the last speaker.

Here Gaskell portrays three ‘types’ of people: the sceptic, the unwavering believer, and the uncertain (easily influenced) follower. In creating these polarised and undecided characters, Gaskell plays with the concept of supernatural belief, largely as a topic of conversation and entertainment between the women. The concordance lines for ghost* in Cranford demonstrates the oral nature of ghost-story-telling (in this case specifically among women) in the nineteenth century. The Dickens Museum exhibition aims to demonstrate the influence that Dickens had on the ghost story genre, so the idea that Gaskell is also perpetuating ghost stories, the evidence that Cranford has the most (relative frequency) references to ghosts, and the knowledge that this was initially published in Household Words, provides a great starting point to consider the relationship between Dickens, Gaskell and ghost stories.

‘To be Read at Dusk: Dickens, Ghosts and the Supernatural’ will run at the Charles Dickens Museum from the 5th of October 2022 until the 5th of March 2023. The admission fee is covered in the price of general admission to the museum. Advanced tickets can be booked here.

References

*You can test the frequency difference between two corpora using the log-likelihood wizard, created by Paul Rayson.

- Dickens, Charles. (1859). ‘The Haunted House’, All the Year Round.

- Mahlberg, M., Stockwell, P., Wiegand, V., & Lentin, J. (2020). CLiC 2.1. Corpus Linguistics in Context, available at: clic.bham.ac.uk.

- Rayson P., Berridge D. and Francis B. (2004). Extending the Cochran rule for the comparison of word frequencies between corpora. In Volume II of Purnelle G., Fairon C., Dister A. (eds.) Le poids des mots: Proceedings of the 7th International Conference on Statistical analysis of textual data (JADT 2004), Louvain-la-Neuve, Belgium, March 10-12, 2004, Presses universitaires de Louvain, pp. 926 – 936. Available here.

All nineteenth-century novels and novellas were accessed via the CLiC Web App.

Please cite this post as follows: Eastman, A. (2022) ‘To Be Read at Dusk’: Ghost Hunting in the CLiC Corpora [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from [https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2022/07/20/dickensghosts/]

Join the discussion

1 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?Comments