This post, penned by Dr Rosalind White (@DrRosalindWhite), will provide an overview of how our CLiC Web App can be used as an innovative historical research tool to cross-reference or verify historical details. This can help writers save time and energy, as well as quickly immerse them in the particulars of their preferred period. You can download this post in handout form here.

As a writer of historical fiction, you might often find yourself wondering if a specific phrase, idiom, or figure of speech would have existed in the cultural vernacular of your chosen era.

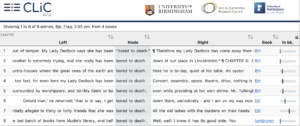

Say your novel is set in the early nineteenth century… you might need to check if the idiom ‘bored to death’ can be uttered by your protagonist.

CLiC can tell you that the answer is yes, and that Lady Deadlock (of Charles Dickens’s Bleak House) was partial to the phrase.

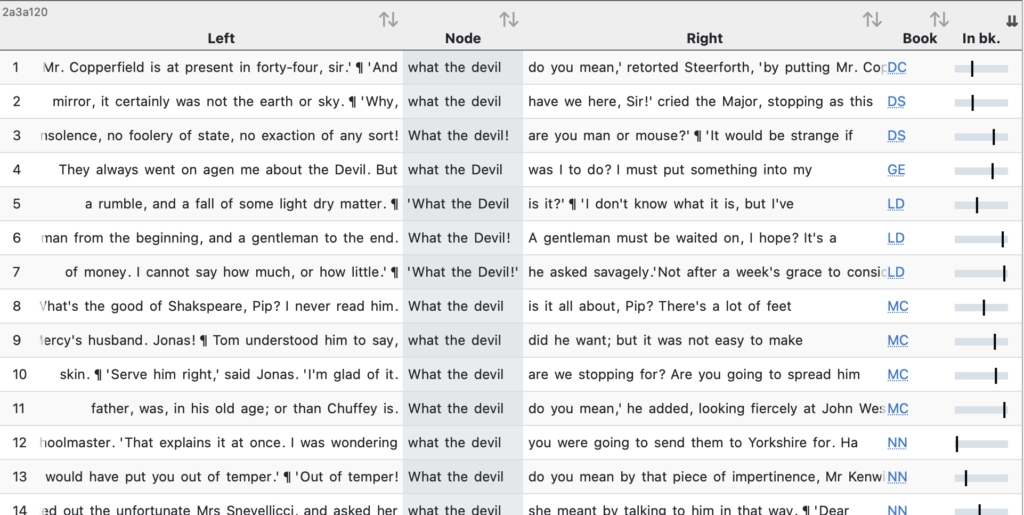

Maybe you need to know if your heroine can exclaim ‘what the devil’?

CLiC can inform you that though the phrase would have been in use, it would have been predominantly used by men.

Perhaps you find yourself wondering the following…

- If your youngest character can refer to their parents as ‘Mum and Dad’? (Yes to Mum, but no to Dad.)

- If your hero would have been termed a ‘scientist’? (No, not in the early nineteenth century).

- If two girls would have dubbed each other ‘best friends’? (Yes).

- If your character could refer to something as ‘cool’? ( Only to indicate temperature, standoffishness, or calmness, or in reference to money — as in ‘a cool hundred a year’ — but not as an expression of admiration or agreement.)

Or maybe you’re looking for a source to learn more about a specific topic, but you’re not sure which Victorian novel will have the answers…

CLiC has you covered:

- An early nineteenth-century novel that discusses the difficulties of courtship? George Eliot’s Middlemarch is your best bet.

- A mid-Victorian novel that heavily features the railway? Turn to Armadale by Wilkie Collins.

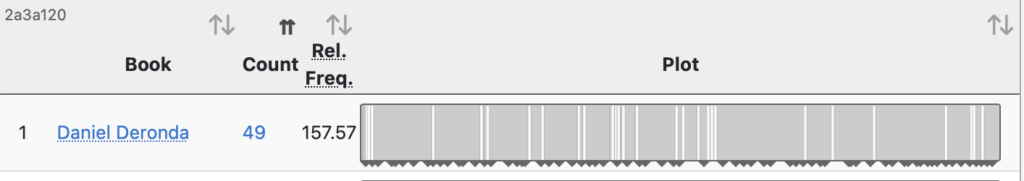

- Or maybe one that contemplates gambling? CLiC recommends, George Eliot’s Daniel Deronda.

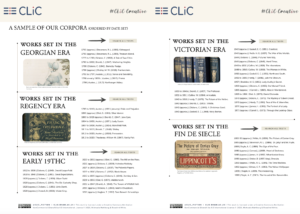

Building Your Corpora

The following handouts will give you an overview of the different periods that make up the long nineteenth century. This is followed by a sample of CLiC’s texts grouped according to era. Please note, this grouping is indicative of when the story is set not when it was penned by the author or when it was published.

If you would like to build your own corpus of texts yourself you can go to clic.bham.ac.uk, click ‘concordance’, and select these texts from the drop-down menu under ‘search the corpora’. If you would prefer to automatically select a sample of texts in a given era you can do so by using the following links or by downloading our handout.

- works set in the Georgian era (1714-1837)

- works set in the Regency era (1811-1820)

- works set in the early nineteenth century (1800-1837)

- works set in the mid-Victorian era (1837-1880)

- works set in the fin de siècle (1880-1900)

‘The time is out of joint; O’ cursed spite! That ever I was born to set it right!’ – Hamlet, Act I, Scene 5.

Research Activity: Checking your Manuscript for Anachronisms

This activity can also be downloaded as a handout here.

An anachronism is a chronological inconsistency: an entity, idea or expression that exists outside of the time in which it belongs. Often, a carelessly deployed idiom can derail an otherwise immersive read. Building up historical precision in smaller details does more than just maintain historical authenticity, it can often help support a writer’s overarching story, by inspiring a new theme or plot point rooted in a forgotten aspect of the past.

From ahistorical hairstyles to curiously present-day parlance, anachronisms have the power to “jar” the reader and shake their suspension of disbelief. You can use anachronisms intentionally to create specific effects (you might be writing a story about time travel!). It’s the unintentional ones that you want to avoid.

In storytelling, “suspension of disbelief” is the act of willingly accepting that which one knows to be imagined. It is an essential step on the path to enjoying any work of fiction. As a genre, historical fiction must balance exactitude with clarity. Readers are liable to disengage if they feel as though you have been careless with historical facts or if they struggle to comprehend the world your characters inhabit.

Tip: an anachronism could be a turn of phrase, a custom, a material, a piece of technology, a cultural debate, or a philosophical idea. When it comes to checking historical facts, leave no stone unturned.

Scan through your manuscript so far, and make a note of every phrase, descriptor or figure of speech that might be anachronistic. Note them down. CLiC is particularly useful when it comes to detecting behavioural cultural, or linguistic anachronisms.

Tip: Sometimes, writers deliberately use anachronisms to help their audience engage more readily with a historical period. While intentional anachronisms can create powerful textual effects too many can prevent readers from immersing themselves in your work.

Armed with your potential anachronisms, employ the CLiC Web App as a cross-referencing tool using the following instructions.

- Go to clic.bham.ac.uk, click ‘concordance’, and select your texts from the drop-down menu under ‘search the corpora’ (according to the time period in which your novel takes place). You can automatically select a sample of texts in each era by using the following links:

- works set in the Georgian era (1714-1837)

- works set in the Regency era (1811-1820)

- works set in the early nineteenth century (1800-1837)

- works set in the mid-Victorian era (1837-1880)

- works set in the fin de siècle (1880-1900)

2. Select ‘all text’ under the subsets option. If your anachronism is likely to occur in dialogue, you can select ‘quotes’. All texts in CLiC have been marked up so that it is possible to focus searches on the direct speech of the fictional characters, we refer to such text as ‘quotes’.

3. Type your potential anachronism under ‘search for terms’ and hit enter. An asterisk can be used as a wildcard – so mum* would also find mums, and best friend* would also find best friends. Make sure you have ‘whole phrase’ selected.

What anachronisms did you detect in your manuscript? Alternately, what phrases or expressions — perhaps surprisingly — proved entirely in keeping with your chosen time period?

You can note down your findings in the handout provided, and, if you’d like, post them on Twitter under the hashtag #CLiCCreative, or by tagging us @CLiC_fiction.

We will shortly be posting several more research and writing activities to guide you, stay tuned!

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?