Sauntering through London’s nocturnal neighbourhoods fuelled Charles Dickens’ imagination and provided him with ample material to people his fictional worlds. What can we learn from his immersive exploration of real-world urban landscapes? In the following activities we’ll take a step back in time using the CLiC Web App to journey through Victorian London via Dicken’s oeuvre. Previous #CLiCCreative posts by Dr Rosalind White are available here. This post is also available as a handout.

Perpetually plagued by bouts of insomnia and writer’s block, Charles Dickens spent many hours wandering London’s streets in the dead of night. He famously conceived of the city as a ‘magic lantern’ that invigorated his creative process and ‘supplied something to [his] brain’ (Letters 4: 612).

His contemporaries credit him with a ‘clutching eye’ and ‘a power of observation so enormous that he could photograph almost everything he saw’ (Letters 3: iv).

Dickens would have no doubt been aware he was practicing an art known as ‘Flanerie’. The concept of the flaneur emerged on the scene in mid-nineteenth century France, and describes an urban observer who wanders through a city, taking in its ever-changing sights and sounds.

‘Men have been chained to hideous prison walls and other strange anchors ‘ere now … but few have known such suffering and bitterness at one time or other, as those who have been bound to Pens.’ – Charles Dickens, writing in a letter to Angela Burdett Coutts in 1843. (Letters 3: 500)

Tip: Among all the characters Charles Dickens depicted, none have played as pivotal a role in his literary oeuvre as the city of London itself. How would you characterise the setting of your novel? Is its ‘personality’ as distinct or dynamic as Dickensian London?

‘A day in London sets me up again and starts me. But the toil and labour of writing, day after day, without that magic lantern, is IMMENSE!!! … my f igures seem disposed to stagnate without crowds about them.’ – Charles Dickens, writing in a letter to John Forster in 1846. (Letters 4: 612)

Research Activity: Finding Your Inner Flaneur

This activity can also be downloaded as a handout.

Go to clic.bham.ac.uk, click ‘concordance’, and select several texts from the drop-down menu under ‘search the corpora‘, according to the period in which your novel takes place. See our earlier ‘building your corpora‘ handout for further guidance.

Select ‘all text’ under the subsets option.

Type one of the terms noted below under ‘search for terms’ and hit enter. You can also use a specific location like ‘London’.

city, court, crowd, explore, lane, neighbourhood, public, river, road, run, saunter, street, stride, stroll, suburb, town, walk, wander.

Remember, an asterisk can be used as a wildcard – so street* would also find streets. If you’d like you can type in multiple terms at once by selecting the ‘any word’ option.

You can click the ‘in bk.’ option on the far right of each result to view each quotation as it appears in the source text.

Repeat your search using an alterate term as many times as you need to.

Perhaps the streets of your novel, like those of Dickensian London, are full of ‘dense brown smoke’ or ‘avoided by all decent people’?

Tracing Dickens’ streets through his oeuvre, can be swiftly done using CLiC’s concordance feature. Using the above search terms, we can map London’s metaphorical movement and unpick how Dickens teases the city’s latent phantasmagoria to the surface.

Once you have run a concordance for you search words, you can organise the display according to specific criteria.

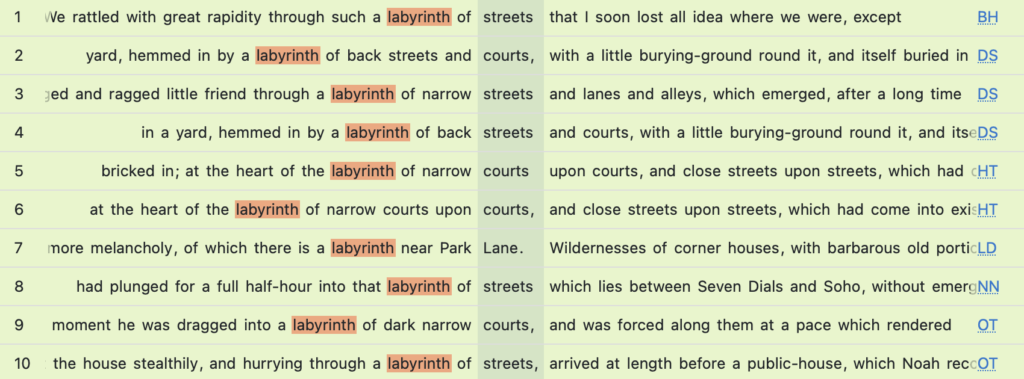

For example, Dickens’ characters can rarely chart a course through the city without being consumed by its labyrinthine streets.

So, if you go to the KWICgrouper and select ‘labyrinth’, CLiC will show you all the lines where your search word occurs together with the word ‘labyrinth’.

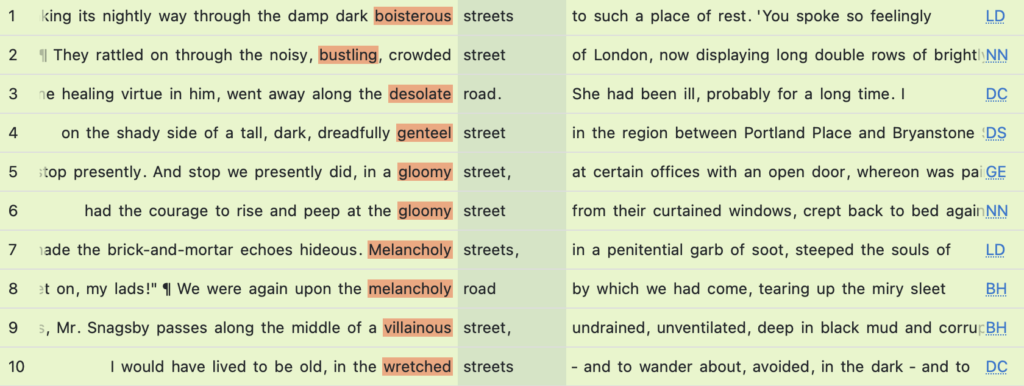

London’s throughfares are often anthropomorphized or endowed with their own emotions. See, for example, Little Dorrit’s ‘melancholy streets, in a in a penitential garb of soot’ (line 7).

In this example, words that indicate emotion (known as modifiers) have been observed in a concordance search for ‘court* street* road* lane*’.

In this example, words that indicate emotion (known as modifiers) have been observed in a concordance search for ‘court* street* road* lane*’.

To group such words together, you can again use the KWICGrouper to pick them out.

The tool does not provide the results for you entirely automatically, but once you have an idea of the words you find interesting, you can use it to display them together.

Now think about how you’d find useful examples that are more specific to the activity of flanerie? The word ‘stroll*’ is a good starting point, as this verb describe a kind of leisurely walking.

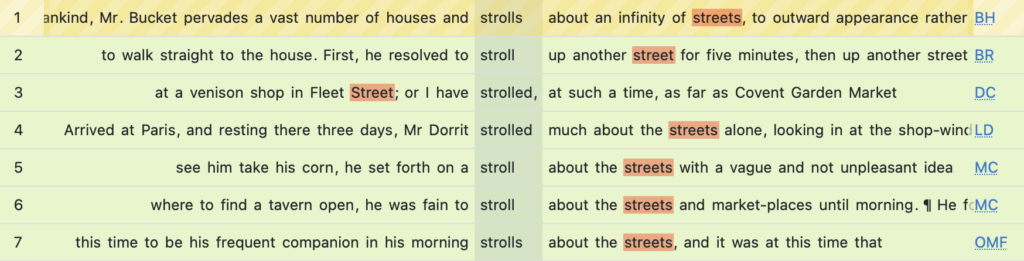

Running a concordance search for ‘stroll*’ across Dickens’ works yields numerous examples of male flânerie.

Mr Bucket, the formidable detective of Dickens’ Bleak House, seems to draw power from London’s streets (line 1), as though the city itself has endowed him with a cosmic understanding of its topography.

David Copperfield takes an aspirational stroll to Covent Garden Market during his lunch break to stare ‘at the pineapples’, then a rare and exotic fruit imported or grown at great expense (line 3).

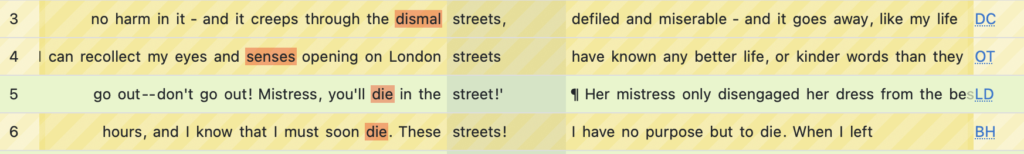

In contrast, feminine movement through Dickens’ urban landscape is fraught with anxiety. In Oliver Twist, Nancy’s ill-fated life begins from the moment she recollects her ‘eyes and senses opening on London streets’ (line 4). Throughout the novel, she is haunted by ‘horrible thoughts of death’ while phantom coffins pass her on the street.

Likewise, in David Copperfield Martha allies the symbiotic pollution of both her and the river Thames with their migration into London: ‘I know that it’s the natural company of such as I am! It comes from country places, where there was once no harm in it and it creeps through the dismal streets, defiled and miserable’ (line 3).

Lady Deadlock (of Dickens’ Bleak House) explicitly charges the streets themselves with her death — her last words scrawled on a piece of paper are ‘I know that I must soon die. These streets! I have no purpose but to die’ (line 6).

OVER TO YOU…

Using the previous examples to guide you, think about what words might be useful starting points for a concordance analysis that captures the city streets. Once you have run your search, look through your results and take note of the impressions that various characters experience while walking. You can record these impressions in your handout the box marked ‘inspiration’.

Does what they see offer a glimpse into the life of another? Do they take special note of certain smells sights or sounds? What is it that captures their attention as they walk? The contents of specific shop windows, the daily routine of passers-by, or perhaps the diversity of the city around them? Do they detect a change in atmosphere, remark on a surprising encounter, or make generalisations about what they observe? How does architecture or transport factor into their impressions? Is the picture “painted” dependent on the weather, season, or time of day?

Use your findings as inspiration to flesh out the world you want your own characters to inhabit. If you were to follow in the footsteps of one of your characters what would you observe? You can note down your ideas in your handout in the box marked ‘application’

Writing Activity: A Step Back in Time

This activity can also be downloaded as a handout.

Using what you have learnt in the previous research activity, take a metaphorical walk around the neighbourhood of your novel. Close your eyes and wander with intention. Have your pen at the ready, as you “stroll” and take a moment to record the impressions that come to you.

Make sure you jot down any relevant sensory information. What would your characters be able to smell? Polishing agents from the local blacking factory? Or perhaps, manure from the many horse- drawn carriages? What would they hear? Church bells? Wiley street vendors touting their wares? How might your impressions shift if you were to “journey” under the cover of darkness?

If you need further inspiration, why not take a leaf out of Charles Dickens’ book and find your own “magic lantern” by strolling around an evocative location?

When you have sufficient material, come back to the twenty-first century and incorporate these impressions into a scene of your own.

Why not post your draft under #CLiCCreative, or by tagging us @CLiC_fiction on Twitter?

Previous #CLiCCreative posts by Dr Rosalind White are available here. You can learn more about the project and download all our resources here.

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?