#CLiCCreative demonstrates how the CLiC Web App can serve as both a creative resource and an innovative research tool for writers of historical fiction. You can find out more about the overarching project here. In this blog post, we’ve provided a keywords guide to our George Eliot Corpus for aspiring writers of historical fiction who want to immerse themselves in the early to mid-19th century. Themes explored include – subjectivity versus objectivity, the clash between tradition and modernity, and the tension between religious beliefs and scientific advancements. This post is also available as a handout.

GEORGE ELIOT (1812-1870)

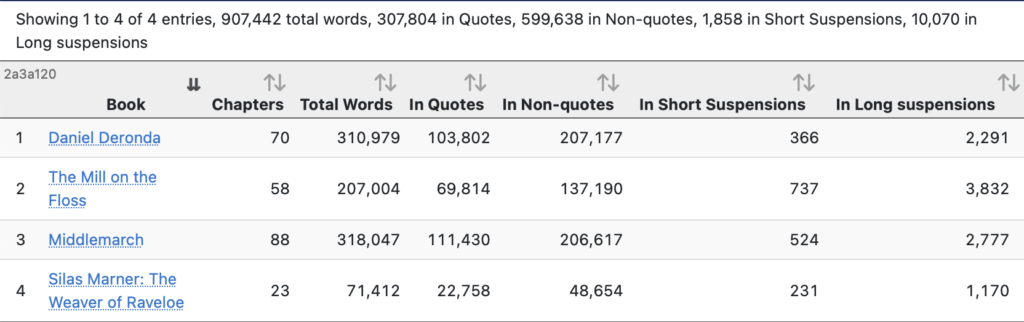

Author of Daniel Deronda (1876), The Mill on the Floss (1860), Middlemarch (1871) and Silas Marner: The Weaver of Raveloe (1861).

Mary Ann Evans, known by her pen name George Eliot, was an English novelist born in Warwickshire. Renowned for her impressive intellect, incisive social observations, and empathetic narrative style, Eliot left an indelible mark on the literary landscape of the nineteenth century.

Serving as a mirror to Victorian society, her novels are peopled by individuals searching for meaning in a rapidly changing world.

Eliot’s hyper-realistic approach to writing allowed her to shed light on the inequalities, injustices, hierarchies, and societal norms of her time. Through this level of detail, Eliot encouraged her readers to practice empathy, question their beliefs and attitudes, appreciate the nuances of daily life, and overall acknowledge the complexity of human psychology.

Her writing traverses a wide range of themes, including – provincial life, the role of women in society, questions of faith and morality and the transformative power of education. These themes are reflected in her lexical choices.

George Eliot Keyword Guide

The ‘keywords‘ tool finds words (and phrases) that are used significantly more often in one corpus compared to another. You can find the full list of keywords in our Eliot corpus (generated using our 19thC reference corpus, excluding Eliot’s texts) here. If you want to learn how to run keywords yourself, please see the keywords section of our CLiC user guide.

The ‘keywords‘ tool finds words (and phrases) that are used significantly more often in one corpus compared to another. You can find the full list of keywords in our Eliot corpus (generated using our 19thC reference corpus, excluding Eliot’s texts) here. If you want to learn how to run keywords yourself, please see the keywords section of our CLiC user guide.

The following paragraphs provide a hyperlinked sample of these keywords, grouped according to theme. If you click on a word, you can run a concordance search for it across George Eliot’s works.

Once you have selected a keyword you can use the ‘filter rows‘ option or the ‘KWICGrouper‘ to tease out or highlight any patterns you come across. Why not print-screen your findings and send them to us on Twitter under the hashtag #CLiCCreative, or by tagging us @CLiC_fiction

Keywords related to internal thoughts and feelings or subjectivity vs objectivity:

Much of Eliot’s works explore the tension between subjectivity and objectivity – the interplay between personal emotions, perceptions, and biases, and the objective reality of the external world. This theme is intricately woven throughout her novels in various ways.

Collectively, these keywords reflect a range of psychological, emotional, and cognitive elements that contribute to the complexity of human thought and behaviour. What does running a concordance search on them tell you about how to present the subjective experience of alternating characters? How does Eliot use these words to highlight the interpretive nature of human experience? See, for example, ‘seemed’, ‘something’, ‘reasons’, ‘if’ and ‘resolve’.

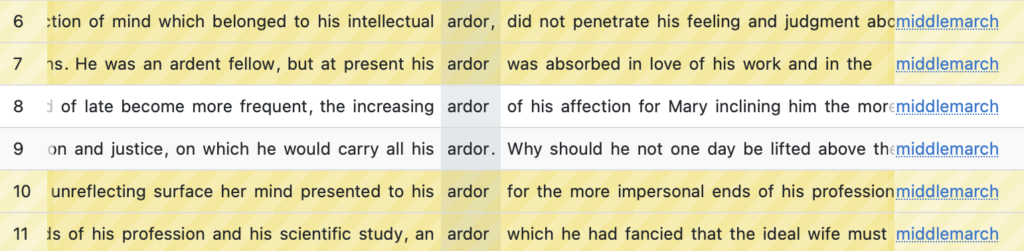

What surprises do you run into along the way? Take the word ‘ardor‘, for example. In Middlemarch this word is frequently used by Lydgate, not to refer to his romantic inclinations but in reference to his medical career.

What does running a concordance search for words like ‘self’, ‘egoism,’ ‘memories’, ‘life,’ ‘inwardly,’ and ‘notion’ tell you about how the concept of selfhood and identity may have differed from its modern equivalent?

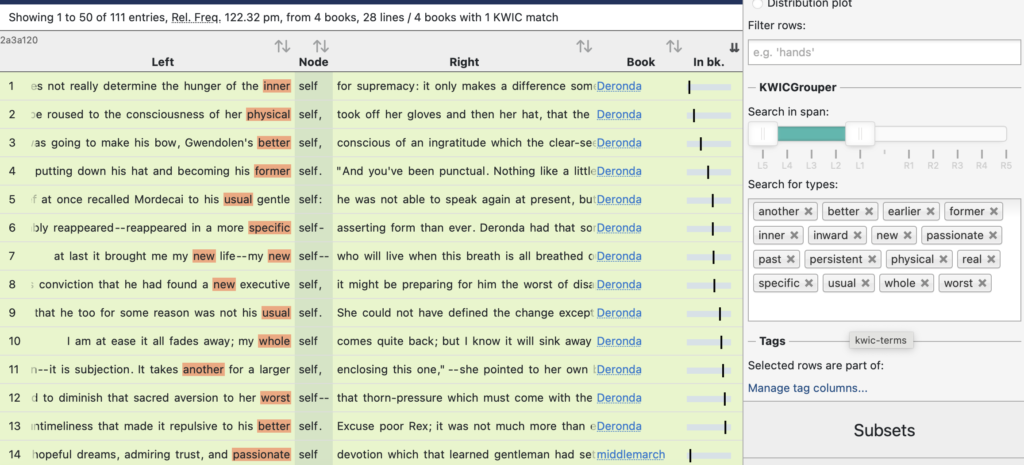

See, for example, the words that preface ‘self’: collocates like the and that indicate existential concern; others introduce a temporal dimension (past, earlier, former); emphasise a sense of authenticity (specific, real); introduce a comparative element (better, worse, worst); or bring a character’s emotions to the fore (passionate, ardent).

Most noticeable in Eliot’s works are collocates of self that differentiate between an internal and external self (inward, inner, persistent); imply a holistic or definitive view of the self (whole, complete); or emphasise moral evolution (another, new, different).

What can you glean from these concordance searches regarding how individuals in the past many have conceptualised their own identities?

You can group these words together using the KWICGrouper.

Keywords related to religion vs science and / or tradition vs modernity:

new, fact, hospital, spiritual, knowledge, medical, judgment, vicar, belief, ideas, rector, religion, clergyman.

In her works, Eliot often delved into the tension between tradition and modernity, as well as the clash between religion and science, most notably in Middlemarch which explores the changing economic landscape of England during the Industrial Revolution.

How does Eliot present a nuanced exploration of the interplay between tradition and modernity, and religion and science?

What can you learn about how individuals may have grappled with these issues in the past?

Think about the ways in which certain words are used – how do they reflect the complexity of the societal changes occurring?

Take note, for example, of what different collocates of the word ‘religion’ imply.

Your, my, his, and her indicate a sense of ownership or individual relationship with one’s faith; father’s points to the generational nature of religious identity; while national, our and people’s link religion to a sense of communal or cultural identity.

Words like, no, other, Jew’s, Hebrew, and high, on the other hand emphasise the distinctions and tensions between different religious beliefs, while adjectives like fundamental, purified, spiritual, true, and vital can give us insight into the perceived qualities of religion itself during this time.

You can group these words together using the KWICGrouper.

Keywords related to patterns of speech:

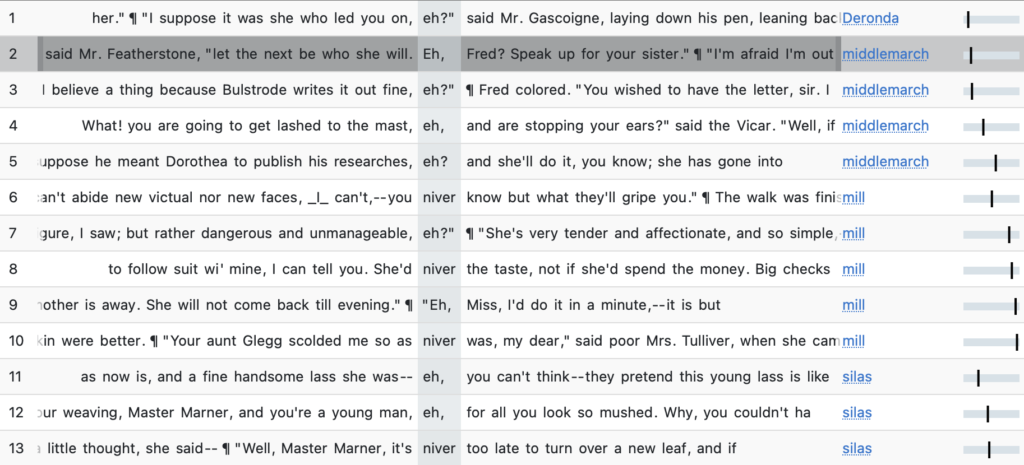

allays, rather, bit, might, hinder, beforehand, seemed, something, should, niver, chiefly, eh, lest.

What can you learn from running a concordance search on the above terms and examining the context in which they were used? Does this inform how you might use the term yourself?

Words such as ‘rather,’ ‘bit,’ and ‘might’, for example, introduce a level of uncertainty or reservation to a conversation, indicating that the speaker is not expressing something definitively. Likewise, words like ‘might,’ ‘should’ and ‘lest’ introduce a conditional aspect in which one’s opinions or statements are contingent on certain conditions or possibilities.

You can use the CLiC Web App to run a concordance search to trace how these keywords are used in conversation by selecting the subset ‘quotes’. In CLiC, quotes represent the passages of text enclosed within quotation marks, indicating direct speech by fictional characters. Can you detect differing patterns of speech according to a character’s gender, age, marital status, occupation or social class?

Note for example, which characters tend to use qualifiers like ‘rather’, ‘bit’ and ‘might’ or how Eliot makes use of regional or colloquial expressions like ‘niver’ and ‘eh’. How might you go about making such linguistic differentiations in your own writing?

A full list of keywords in our Eliot corpus (generated using our 19thC reference corpus, excluding Eliot’s texts) is available here.

—-

You can note down your findings in the handout provided, and, if you’d like, post them on X (formerly Twitter) under the hashtag #CLiCCreative, or by tagging us @CLiC_fiction.

Please cite this post as follows: White, R. (2024) #CLiCCreative George Eliot Keywords Guide [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from [https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2024/02/26/eliotkeywords/]

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?