This is the second post of the mini-series “Bringing Dickens to the Stage”, in which actor Gerald Dickens (@DickensShows on Twitter) recounts his personal connection with the works of his great great grandfather, Charles Dickens. The post is brought to you as part of the BMI Lockdown Life initiative, in collaboration with the Birmingham & Midland Institute. Join the conversation on Twitter with #BMILockdownLife.

In my previous blog post I explained how I discovered the delights of performing the works of my great great grandfather Charles Dickens, when I was asked to recreate one of his most famous performances as a fundraiser in 1993. This post gives a brief account of Dickens’ performing career.

Dickens – An actor writing his own scripts

I knew little about the theatrical career of Charles Dickens, but my father had recommended that I read various biographies and it soon became apparent to me that rather than being an author who read from his own works, Dickens was more of an actor who wrote his own scripts. The love of theatre was apparent from his earliest years and in The Uncommercial Traveller he wrote a remembrance of his childhood town (actually Chatham in Kent but rather unkindly fictionalised as ‘Dullborough’) he recalled his early memories of visiting the theatre, remembering how

“Richard the Third, in a very uncomfortable cloak, had first appeared to me there, and had made my heart leap with terror by backing up against the stage-box in which I was posted, while struggling for life against the virtuous Richmond. It was within those walls that I had learnt as from a page of English history, how that wicked King slept in war-time on a sofa much too short for him, and how fearfully his conscience troubled his boots […] Many wondrous secrets of Nature had I come to the knowledge of in that sanctuary: of which not the least terrific were, that the witches in Macbeth bore an awful resemblance to the Thanes and other proper inhabitants of Scotland; and that the good King Duncan couldn’t rest in his grave, but was constantly coming out of it and calling himself somebody else.” (The Uncommercial Traveller, Chapter XII)

As a young man living in London, Charles would continue to indulge his passion for the stage and even took lessons from a professional actor, presumably with the intention of exploring the possibility of making it his career; to that end he even managed to secure an audition at The Covent Garden Theatre, but never made the appointment due to his health. The fact that he never tried again suggests that the reality of a life on the stage did not tally with his desire for a comfortable, even slightly foppish, lifestyle. Dickens was finding success as a journalist which would of course lead to his writing career and wealth way beyond that which he could have achieved by treading the boards of the provincial theatres. The financial aspect is an important one – Dickens wasn’t greedy for money, but his entire outlook was shaped by the memory of his father’s imprisonment for debt and his own humiliating days as a twelve year old slaving in Warren’s Blacking factory to bring a few pennies into the family. Making money was not so much a beacon of success to Charles Dickens, but a signal of triumphing over failure.

From his earliest works theatre featured strongly. In Sketches by Boz, he wrote of ‘Private Theatres’ and in his first novel The Posthumous Papers of the Pickwick Club, one of the first characters we meet is the itinerant, and wholly untrustworthy, actor Mr Jingle.

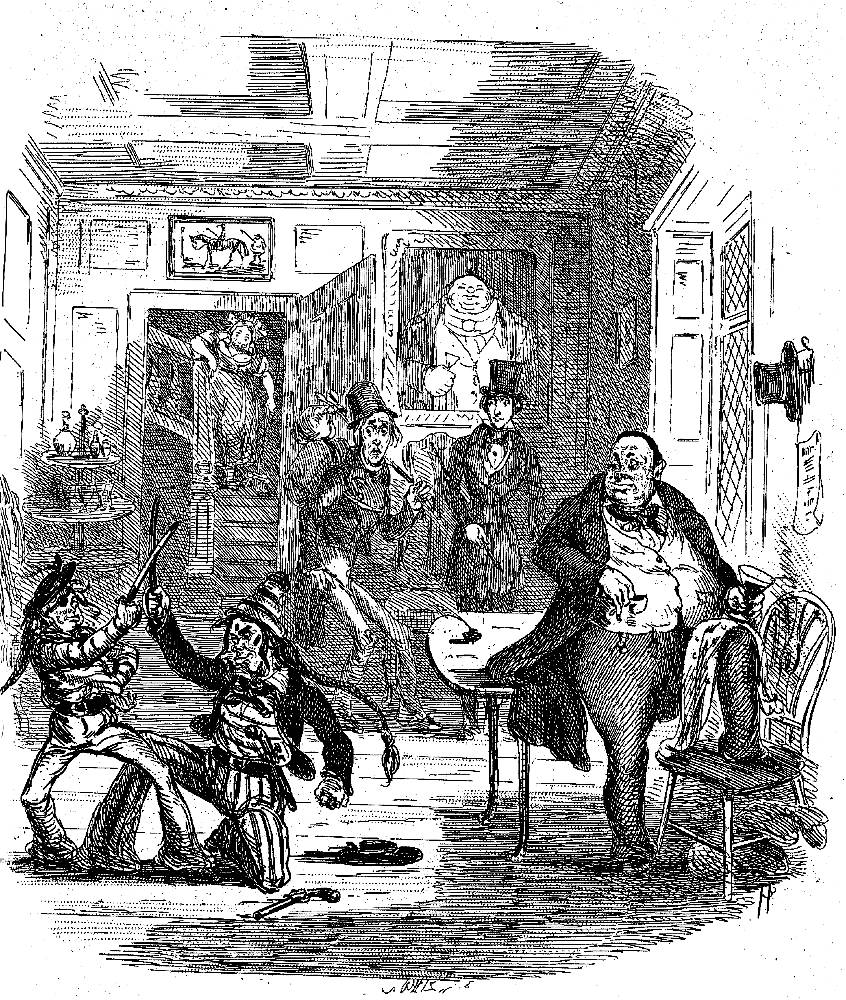

It was in his third novel, however, that Dickens really brought the stage to his literature. In Nicholas Nickleby our hero accompanied his ever-trusting companion Smike, set out to walk from London to Portsmouth in the hope that they may find employment onboard a ship. During their journey they find themselves at a roadside inn where they meet Mr Vincent Crummles and his theatrical troupe. The scenes that follow are among the funniest in Dickens’ work and the love of his subject clearly shines through.

Dickens, the celebrity, taking to the stage

As the young anonymous author Boz morphed into Charles Dickens the celebrity, so he was able to surround himself with likeminded folk and take to the stage more seriously. Dickens and others in his circle formed an organisation called The Guild of Literature and Art which was ostensibly created to assist the families of artists who were left in poverty. The group, made up of notable names from the fields of literature, theatre and the visual arts would stage great theatrical events in order to raise money; of course, besides its philanthropic ideals, it was also a splendid excuse for Dickens to become an actor manager and indulge his passion.

Over the years the troupe performed plays such as Ben Johnson’s Every Man and his Humour, and Elizabeth Inchbald’s farce Animal Magnetism, whilst Edward Bulwer-Lytton, another founder member of the Guild, wrote Not So Bad As We Seem which was performed in his ancestral home Knebworth House. What all these productions had in common was the name of Charles Dickens at the head of the cast list. He was supported by such luminaries as fellow author Wilkie Collins, the artist Augustus Egg and Mark Lemon, the editor of Punch magazine.

In 1856 Dickens suggested to Collins that they collaborate on a brand-new play which would be performed in Charles’ own home in Tavistock Square the following January and which was called The Frozen Deep.

Charles Dickens threw himself into the project with huge verve. He began to convert his home into a theatre which would hold around 93 guests, at least ten of whom “will neither hear nor see!” His letters during the weeks prior to the performances were a flurry of preparation. He spoke of a great lighting effect that would open the show:

“I should very much like you only to see a Sunset – far better than anything that has ever been done at the Diorama or any such place. There is a Rehearsal to night (no one here but the company), and this Sunset, which begins the play, will be visible at a quarter before 8: lasting ten minutes.” (letter to Mrs Brown, 2 January 1857)

Scenery had to be completed and he had enlisted a great artist to work on the backdrops: Clarkson Stanfield, a Royal Academician, was creating a splendid arctic vista for the final act, but Dickens wrote to him as if he were a stage hand at one of the London theatres, “My Dear Stanny…I forgot that there are all those Icicles to be made. Could you manage to come tomorrow afternoon – direct that operation before dinner – take your mutton with us – and then take the Rehearsal? Do if you can.” (1 January 1857). The entire cast, which included members of his own family, were rigorously rehearsed to a strict timetable until the day of the first performance arrived.

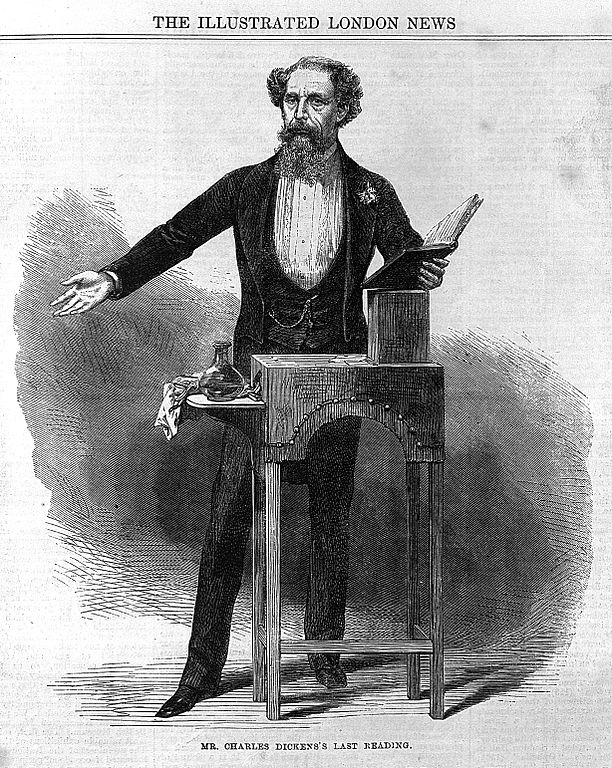

The performance was the talk of the town and The Illustrated London News reported that Dickens’ role of Richard Wardour “required the consummate acting of a well-practised performer. Too much praise cannot be bestowed on the artistic interpretation that it received from him. It was a fervid, powerful and distinct individuality, thoroughly made out in all its details.” His talents as an actor were not in doubt. But he was restless and wanted more, in fact he wanted much more: he wanted all of the applause – not a share of it. Charles Dickens was about to embark on his new career, that of a professional reader.

As was natural for a man of Dickens’ standing, he had been called upon to read from his own works by various charitable organisations and these performances had been well received by all who witnessed them and soon he realised that there was quite a lucrative opportunity in performing for his own benefit. From the very start Charles went to great lengths to not only read a passage from a book but to use his theatrical experiences to create a carefully produced script. Scenes were cut back to their basics, devoid of description, because the performer could create a face, an atmosphere, a scene purely by changing his expression, stance and demeanour.

As for his physical surroundings Dickens created a set which was simple and carefully considered. The reading desk, covered in maroon fabric and trimmed with gold braid, was slender so that it didn’t mask too much of the performer’s body. Rather than being a tall lectern, the desk was quite short but there was a small box which sat on the top for the reader to rest his hand on, meaning that when he referred to the book his face was not in shadow. To one side of the desk there was a little shelf which held a carafe of water and a handkerchief. The desk wasn’t purely a physical necessity but became a prop in its own right; for example during Fezziwig’s party in A Christmas Carol, Dickens would drum his long fingers on the table thereby creating a puppetry representation of the old man dancing to Sir Roger de Coverley.

A skilled and talented performer

At first the public filled the halls out of a sense of curiosity, to see the great Dickens who had enriched their lives with his stories. In those early days Charles could probably just have read a list of characters and the audience would have gone home happy, but the fact that he was such a skilled and talented performer created a unique art form and the shows became the hottest ticket in town.

Charles, or ‘The Inimitable’ as he called himself, never took his eye off the ball and went to great lengths to make the readings perfect: he created a gas lighting rig that bathed him in bright light so that no facial expression was lost, and to complement that he erected a huge maroon-coloured screen behind him so that his pale features stood out clearly. The screen was not made of curtain but of a solid material meaning that it also acted as a sounding-board, a necessity in auditoria that sometimes held up to 3,000 people.

A true theatrical man, Dickens left nothing to chance in bringing his works to the stage.

In my next post I will look at the gestation of one of his notorious performances: Sikes and Nancy.

Further reading

- Dickens, C. (1995). The British Academy/The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens: Volume 8: 1856-1858 (G. Storey & K. Tillotson, Eds.). Oxford, New York: Oxford University Press.

- Dickens, G. (2020, June). Bringing Dickens to the Stage. Part One: A Christmas Carol. [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog.

- Killeen, M. (2018, March 12). ‘High prices, big posters, and great confidence … Town very much excited on the subject’: Charles Dickens on the Birmingham stage in 1848 [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog.

- Radcliffe, C. (2020, June). Sikes and Nancy: Dickens and audience [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog.

This is fantastic. I am enjoying reading these posts and getting a better understanding of Charles Dickens.