What can historical fiction do for today’s society? The award-winning actor Paterson Joseph’s The Secret Diaries of Charles Ignatius Sancho tells the story of Charles Ignatius Sancho writer, composer, respected ‘man of letters’ and the first known Black person to have voted in a British election. As Paterson writes in the opening pages of his debut novel, his goal was to depict the Black presence on the British Isles, in the form in which he first met Oliver Twist, David Copperfield and Jane Eyre: ‘personally and movingly’.

In this episode of the Life and Language Podcast (available via Spotify and Apple) we talk about Black presence in history, the challenges of writing historical fiction, and seeing the world through narratives (on the page, on the stage or in films). Paterson Joseph tells us about his personal experience of becoming an actor and a writer, and shares his thoughts on the writing of history as performance.

‘If you adopt the rule of writing every evening your remarks on the past day, it will be a kind of friendly tête-a-tête between you and yourself, wherein you may sometimes happily become your own Monitor; and hereafter those little notes will afford you a rich fund, whenever you shall be inclined to retrace past times and places.’ – Charles Ignatius Sancho 1729–1780

Words are Not as Memorable as Image

‘Words are brilliant but they’re not as memorable as image.’

For Paterson, words, while powerful are not as memorable as images. Storytelling sticks when it conjures up an image so vivid it cannot help but linger in one’s memory. The intensity of the scene in which Oliver asks for more in Dickens’s Oliver Twist has the power to set the emotional tone for the rest of the novel.

A useful strategy for conjuring up such images is, in Paterson’s words, to ask yourself what your protagonist ‘saw, smelt and felt’.

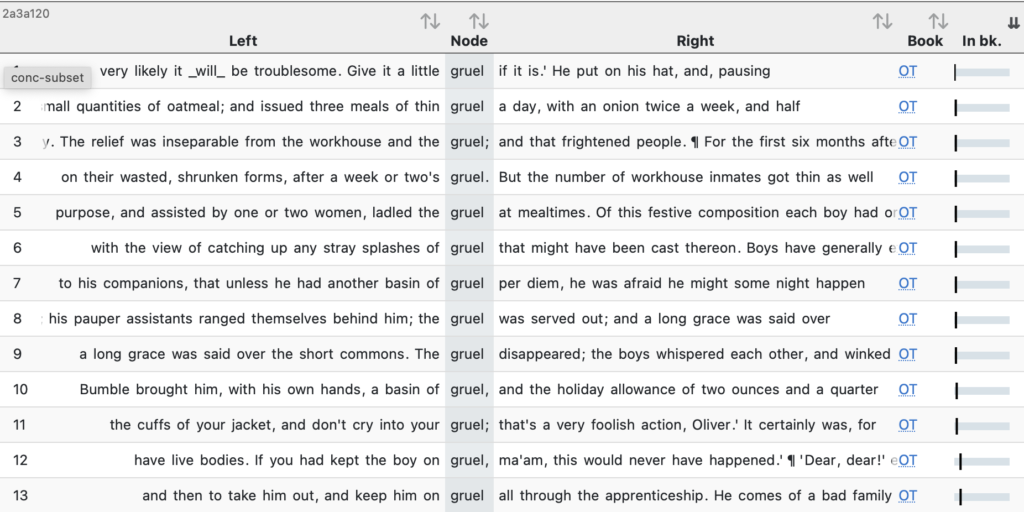

Charles Dickens was a master of sensory storytelling. The CLiC Web App serves as a fantastic tool for mapping his methodology. Dickens famously included vivid descriptions of food in his novels, from Oliver’s grim diet of gruel to the lavish banquets and feasts enjoyed by the wealthy.

If you’d like to gain a more comprehensive understanding of how Dickens expresses and represents sensory experiences, then you can run concordance searches for various words related to the senses of sight, sound, touch, taste, and smell. Here is a list of terms to get you started in your concordance searching:

see, saw, look, observe, watch, glimpse, view, notice, behold, hear, heard, listen, sound, noise, melody, pitch, tone, smell, smelt, aroma, fragrance, odor, scent, stench, taste, savor, flavor, palate, delicious, bitter, sweet, touch, feel, caress, stroke, tactile, sensation.

What patterns can you find?

History as Performance

As Michaela and Paterson discuss, the act of narrating history is, in essence, a performance. Scholars take a particular stance, presenting it in historical form, whether in a textbook or another medium and this “performance”, laden with attitude, becomes part of the historical discourse. In other words, within the historical record there exists a spectrum of truth, interpretation, and outright falsehood. Much of history should be approached with the understanding that our knowledge remains incomplete, that large segments of society have been overlooked, especially in the context of black British history. For Paterson, acknowledging this uncertainty is crucial.

Treating history as a performance can help you infuse emotion and engagement into your narratives, so that ultimately you craft stories that resonate with readers on a visceral level. It is an approach that can add depth and complexity to your characters.

Equally, acknowledging that history is a performance prompts a writer to explore different perspectives and biases and helps them avoid one-dimensional representation of history.

Remember: just like an actor brings their own nuanced interpretation to a role, alternating historical figures would have interpreted the events occurring around them in a myriad of different ways.

As Paterson’s vivid retelling of Charles Ignatius Sancho demonstrates, this freedom allows for imaginative storytelling through the exploration of “what if” scenarios.

Charles Dickens was known for his dramatic and theatrical readings of passages from his own works. He frequently performed excerpts from his novels, drawing large audiences eager to hear him bring his characters to life. These readings were not mere recitations; Dickens imbued them with energy, enthusiasm, and even adopted distinctive voices for alternating characters.

Dickens was a keen observer of the injustices of his time. It is likely no coincidence that his characters, like actors in a play, often portray distinct, larger-than-life roles that reflect upon the broader historical context in which he lived. He was acutely aware of the power of public perception and of the often-performative nature of human interactions. His novels, in many ways, served as a stage to critique or comment upon the societal wrongs he saw around him.

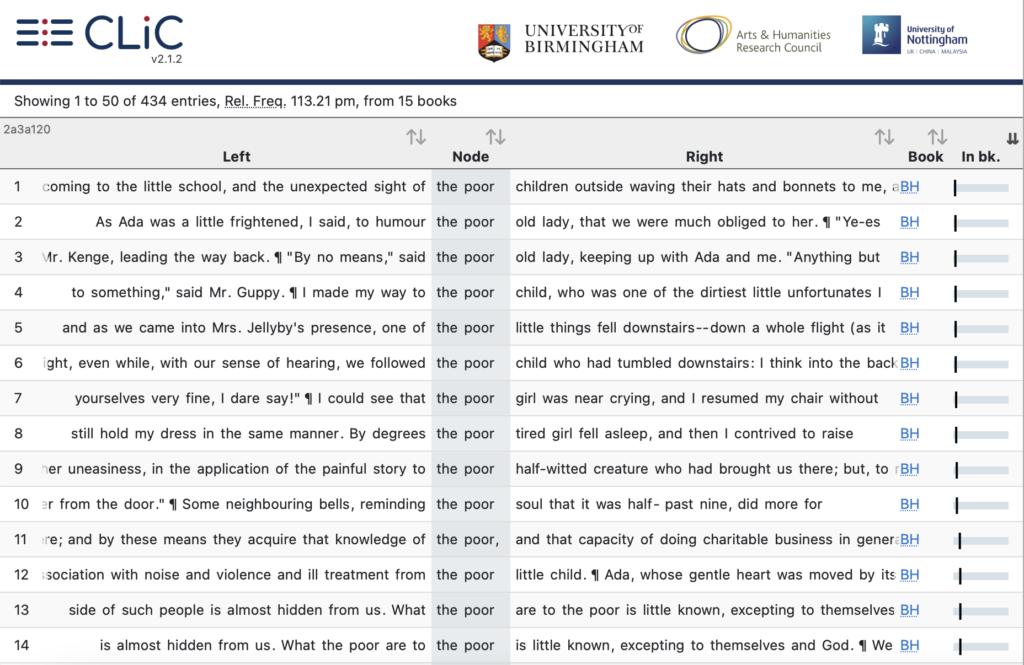

You can trace Dickens multifaceted portrayal of the poor in Victorian England using the CLiC Web App. Consider how his writing effectively evokes sympathy for their struggles and criticises the wider structures and institutions that perpetuated their suffering.

Constructing Around the Bare Bones of the Archive

Remember, research is a subjective enterprise that can be creative as well as academic. In his conversation with Michaela, Paterson cites the writing methodology of writer and historian Dr Sadiya Hartman, a specialist in trans-Atlantic slavery. Dubbed “critical fabulation”, this is a tool Hartman uses to make productive sense of the gaps and silences in the archive. As she puts forth in her book Wayward Lives, Beautiful Experiments (2019), Critical fabulation involves a form of speculative storytelling and imaginative reconstruction of the lives of individuals who are often marginalized or whose stories have been silenced or overlooked in historical archives.

Engaging in critical fabulation can enable one to disrupt traditional historical narratives that may perpetuate oppression or overlook the complexities of the lives of marginalized individuals. It is an approach that involves a creative and speculative engagement with historical fragments and archives, filling in gaps with empathetic reconstructions that consider the emotional and subjective dimensions of the lives being explored.

For Paterson’s research on Charles Ignatius Sancho this meant ‘taking the paucity of the archive and infusing it with cross references from other bits of other people’s lives’, noting where individuals were similar to the person that he was investigating and then using his imagination and empathy to ‘look at the world through their eyes,’ and ‘breathe life into them’.

Sancho and Me for One Night Only

‘Charles Ignatius Sancho’s inspirational story demonstrates the absolute and continuing need for equal access to education and the arts. Through ‘Sancho and Me’, Paterson Joseph reveals the limitless potential the arts have in transforming lives and changing history’. – Dr Caroline Radcliffe, Reader in Drama and Performance at the University of Birmingham.

To mark Black History Month, the Department of Drama and Theatre Arts at the University of Birmingham hosted two free performances of Paterson’s new show, which immortalises the life of Charles Ignatius Sancho – the first man of African Heritage to vote in Britain almost 250 years ago.

The performance explored ideas of belonging, language, education, slavery, commerce, violence, threat, politics, music and love – and where these themes intersect with Paterson’s own story of being Black and British.

The performances took place on 10 and 11 October 2023 at George Cadbury Hall.

#CLiCCreative demonstrates how the CLiC Web App can serve as both a creative resource and an innovative research tool for writers of historical fiction. You can find out more about the overarching project here. If you’ve enjoyed this post then please share it on X (formerly Twitter) under the hashtag #CLiCCreative, or by tagging us @CLiC_fiction. You can listen to Professor Michaela Mahlberg and Paterson Joseph’s conversation in its entirety by listening to the Life and Language Podcast.

Please cite this post as follows: White, R. (2024) #CLiCCreative Lessons from Paterson Joseph on the Writing of History as Performance [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from [https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2024/01/25/paterson/]

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?