Martin Wynne (@MartinJWynne on Twitter) is a digital research specialist at the University of Oxford. Martin is based in the Bodleian Libraries, where he is responsible for the Oxford Text Archive, which also involves managing the distribution of the British National Corpus (BNC).

From almost the very beginning of the digital era, people have used computers to help them to explore and analyse literature. They worked out ways to represent letters and punctuation with numbers, to enter and store texts on a computer, and then wrote programmes to count words, re-order items, and explore texts in various ways. Pre-digital traditions like Bible concordances and textual exegesis found a natural home on the computer, as did stylometry and authorship attribution studies.

For a long time there were few standards for representing text, and it was difficult to transfer data from one computer to another. For these and other reasons it was very difficult to share resources and build communities of researchers who were working on digital texts. In around 1976 the Oxford Text Archive was set up to provide a repository for digital texts, as well as associated services to create texts, such as scanning and optical character recognition. Staff in Oxford also built analysis tools such as the Oxford Concordance Programme to make it easier to work with the digital texts.

There were other similar initiatives – John Dawson’s electronic text archive at the University of Cambridge, for example – but the OTA is the only one in continuous existence since that time, and is still going strong.

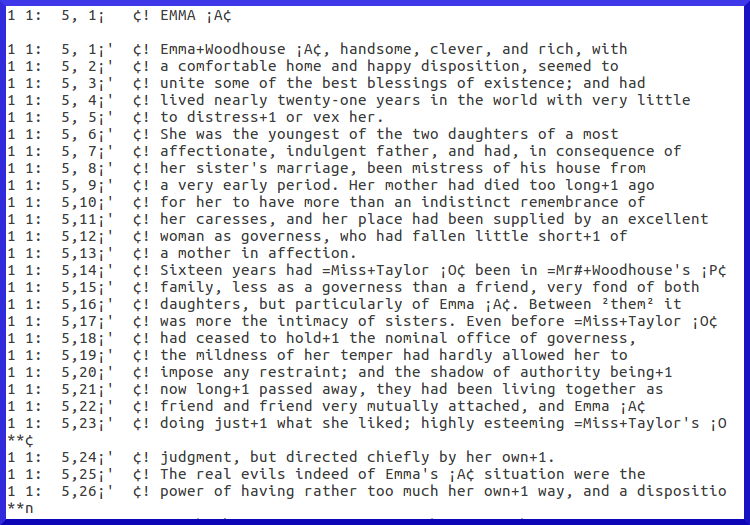

The text of Emma here is an example of a text entered on the computer for use in literary analysis in the 1970s for a stylistic study of Jane Austen’s prose. It’s not designed for reading, but for processing with a specific computer programme, and the encoding reflects a punch card entry method. [1]

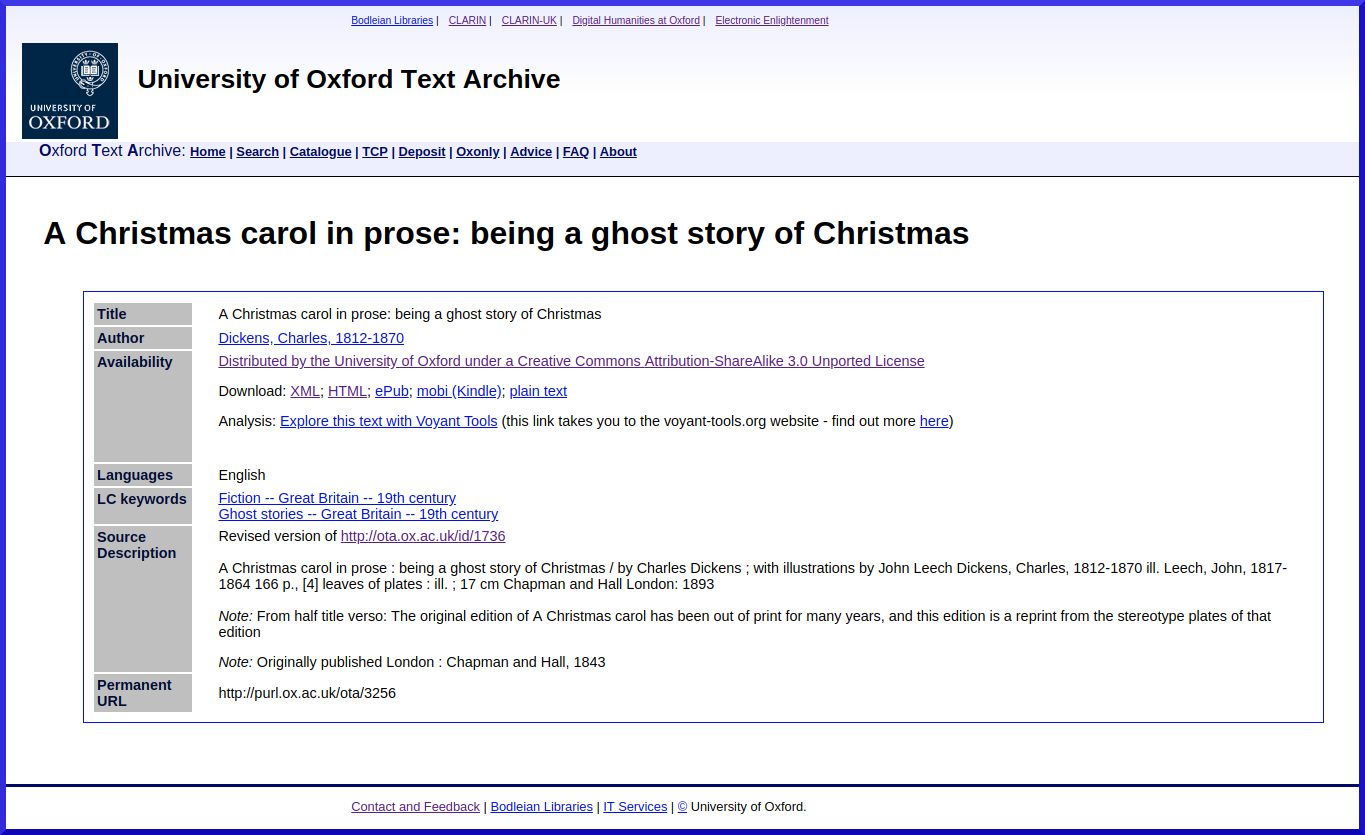

There are numerous Dickens texts in the OTA, free to download, in various formats, including ones for reading in the browser and on an e-book reader, as well as ones for computer processing. [2]

There came a time in the 1990s when digital editions of literary works on CD were popular, but these could be expensive and difficult to use. [3][4] They were not necessarily based on authoritative editions, and you couldn’t correct, or otherwise edit or update the text. Some of the texts on CD had hyperlinks to other material such as contextual information and historic documents. These disks were only available at a fairly high cost, for use on specific high-end desktop computers, only worked for a short time before becoming obsolete, and the links to other online materials are now all broken. Another problem with the CDs was that you were tied to the software on the disk. In practice, all you could really do with the texts on CD was search for quotations (although this should not be underestimated, as it could be a real time-saver!).

Texts are now, of course, available not on disks, but online, usually for free if they are out of copyright,[5] and a wealth of contextual information can usually easily be accessed online, for example on Wikipedia.

Digital texts have made new forms of research possible. As an example, a substantial study of patterns of words distribution and co-occurrence in Dickens’s prose was carried out by Masahiro Hori and published in 2004. This work could not have been carried out without digital texts and computer processing. Thanks to analysis on the computer, Hori is able to show that the word ‘very’ occurs in close proximity to the word ‘gentleman’ significantly more frequently in the novels of Dickens than in a reference corpus of contemporary texts, a statistical fact which he is able to cite as evidence to indicate a tendency to exaggerated descriptions of appearance and behaviour in characters described as ‘gentleman’. The computational analysis helps to identify and explain a stylistic tendency in Dickens’s prose. [6]

The output of Hori’s research is a printed book, which rather painstakingly explains the statistical results of word frequency and word co-occurrence analysis, with an accompanying discussion of the stylistic effects created by the distribution patterns. The book might be in your library if you are lucky, but currently costs £96 on Amazon. The texts and software that Hori used are not made available as outputs of the research project, making it difficult to try to reproduce or extend the research. As a result, access to Hori’s findings is limited in a number of ways.

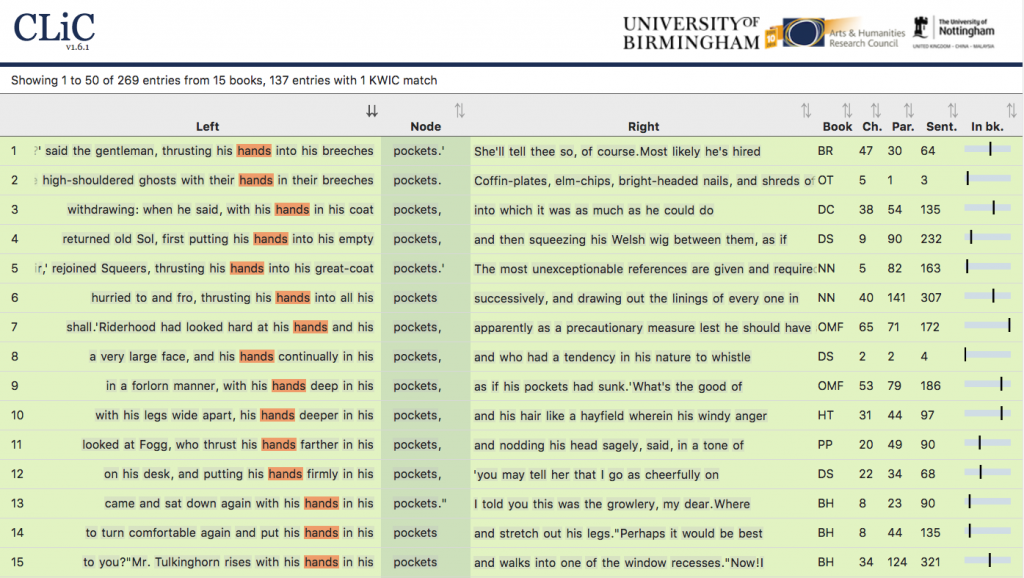

In this context, CLiC is a big step forward, because it allows anyone who can get online to explore for themselves the text, word frequency lists, clusters of words, collocations, ‘suspensions’, reported speech, etc. And this can be done not only from a desktop computer, but from a mobile device as well.

This allows researchers and other enthusiasts to do more than what was possible with the different digital editions of the past. While it is possible to search the online and downloadable electronic versions, for example from Project Gutenberg, with CLiC you can do much more. Thanks to the annotations that have been added to the text for suspensions and quoted speech, for example, you explore the ways in which the narrative is constructed in sophisticated ways. The work that has gone into building the interface means that you can do a lot more than searching for individual word forms in a single text.

However, not all of the problems of sustainability and interoperability have gone away. In ten years’ time, there is a chance that interactive websites like this will be like the CD-ROMs of today. And researchers are still restricted to the texts which the CLiC research team have put into their collection. It would be good if you could do these types of searches with a much wider range of texts from different authors. It would be good if a wider range of search and analysis functions were available to use on these and other texts. So there is plenty of work to do to keep updating, expanding, and maintaining CLiC, but at the moment, it represents the state of the art in online interfaces for digital literary research.

Please cite this blog post as follows: Wynne, M. (2018, February 6). Dickens and the History of Literary and Linguistic Computing – a (very) short retrospective [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2018/02/06/dickens-and-the-history-of-literary-and-linguistic-computing

References

- [1] Emma http://purl.ox.ac.uk/ota/0012

- [2] A Christmas carol in prose: being a ghost story of Christmas http://purl.ox.ac.uk/ota/3256

- [3] The Dickens Web http://www.eastgate.com/catalog/Dickens.html

- [4] Review: Dickens on Disk https://www.jstor.org/stable/30200426

- [5] Project Gutenberg: Books by Dickens, Charles http://www.gutenberg.org/ebooks/author/37

- [6] Hori, Masahiro (2004), Investigating Dickens’ Style: A Collocational Analysis, Palgrave Macmillan.

Join the discussion

1 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?Comments