In this guest post, Katherine Jackson (Royal Holloway) demonstrates how searching for items of cutlery in the CLiC corpora can shed a light on the cultural context of 19th century Britain and the gender conventions of the time. If you enjoy this post, also make sure to check out her recent Technecast podcast on her cutlery research!

When considering cutlery in nineteenth-century novels, it would be easy to assume that female characters, because they are so central to ideas of domesticity in this era, would be more interested in knives, forks and spoons than their male counterparts. Readers might expect to read of an angel of the house sat at home fretting over her silver spoons and the correct placement of knives and forks on the table. Yet, this is decidedly not what appears in texts of this period — it is men, and notions of masculinity, that are bound up in cutlery. And, as ideas of masculinity changed over the century, so too did the use of textual cutlery.

Figure 1 demonstrates the relationship between masculinity and cutlery; here, the Prince Regent picks his teeth with a fork. In the right corner of the image, his coat of arms (a sign of his identity) displays a knife and fork crossed. Though dated slightly before the nineteenth century, the image shows how closely connected masculinity and cutlery were in the public imagination.

Gendered Cutlery

I came across this unexpected result while exploring the gendering of cutlery using the CLiC web app. In my first investigation I examined the gender of those who used cutlery in texts across the century. In my study, the terms knife, fork, and spoon were individually searched for in the “Dickens Novels” and “19th Century Reference Corpus”, and, after considering the sex of the character who was using or was aligned with the object, each occurrence was placed into one of five categories: “men”; “women”; “un-gendered/situational”; “men and women”; or “not cutlery”. Due to research constrains, it was not possible to search for all words used that might related to cutlery (i.e. plate, knives, flatware, etc.). Knife, fork, and spoon were used as they provide the broadest and clearest references to the items of cutlery. After removing the “not cutlery” category (this included a range of items like pitch-forks and pen-knives), the results clearly show men to be more connected with cutlery — altogether, cutlery relating to men account for approximately 72.2% of all cutlery used in novels.

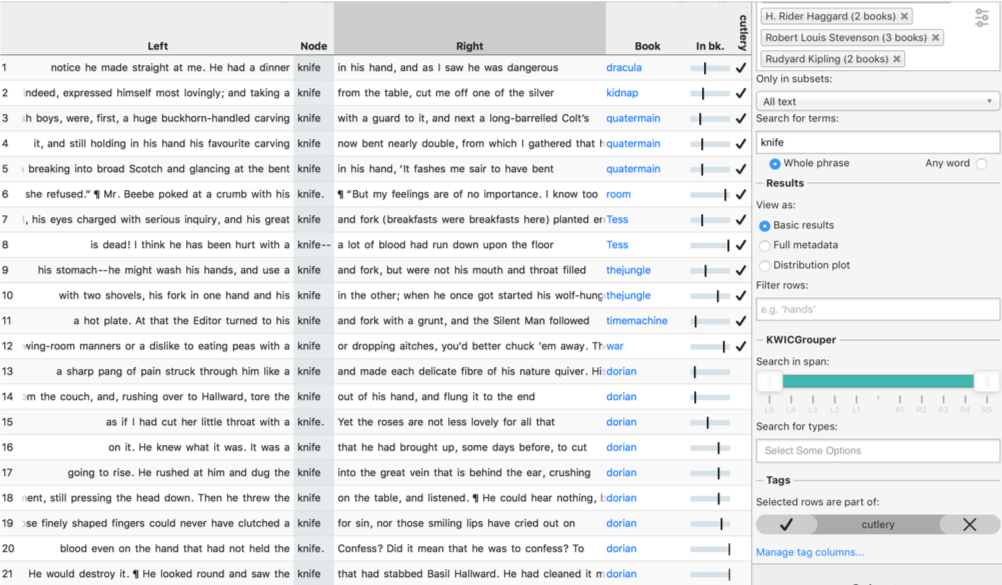

I argue that men’s fascination with cutlery is due to a man’s domestic role in the home — he is the “carver”. For much of the early and middle of the nineteenth century, the most popular dining style was à la Francaise. Broomfield (2007: 102) explains that: “dinner à la Francaise in England simply meant that the host carved the meat, the side dishes were placed on the table so that the guests and family could help themselves, and the meal was done in a series of courses.” As the family’s provider, the carving man dispensed the family’s meat. With all eyes watching, this spectacle was an active demonstration of the masculine householder’s domestic position — as seen in Figure 2, where David Copperfield is attempting to carve, while his wife and friend watch him. Cutlery in novels, then, is commonly used to display a male character’s anxiety about their position in the home.

Changing Times: Changing Cutlery

However, by the end of the century, modes of masculinity had changed; Tosh (1999: 172) has examined how, in the late Victorian period, there was a growing reluctance from men to marry and live a domestic life. Tosh (1999: 174) correlates this change with the rise of a new genre of adventure fiction, where the “heroes are fighters, hunters and frontiersmen [are] distinguished by their daring and resourcefulness”. I wanted to test this in terms of cutlery — can this decline in domestic masculinity be proved through cutlery in novels? Therefore, in my next CLiC study, I searched for the same terms (knife, fork, and spoon) in the “19th Century Reference Corpus”and in works by Kipling, Haggard, and Robert Louis Stevenson, but this time I limited my search to the texts published between 1880 and 1910 (18 texts in total).

I did not use the whole children’s corpus. Kipling, Haggard, and Robert Louis Stevenson’s texts were particularly important adventure fiction novels and are not solely children’s novels. In the last years of the nineteenth century, cutlery evaporated from novels almost completely. In the eighteen books included (after cutting all the non-cutlery) there were a total of 36 references, with seven of the texts having no cutlery in them at all. Considering that the mid-century novel David Copperfield (1850) has 47 references to these words alone, it is clear that by the 1880s, cutlery had ceased to be a significant part of object-relations in fiction. When cutlery is used, it is used in such a way so as to highlight the lack of domesticity that pervades these later texts. For instance, in Allan Quatermain (1887) and Dracula (1897) cutlery is used only as a weapon (see results 1, 3, 4, 5 in Figure 3); a carving-knife and table-knife, respectively, are used by men (one of which is a vampire) to attack others, thus signalling a very different kind of masculinity to the mid-century domestic provider.

Particularly interesting is H.G. Wells’s use of cutlery, which, though infrequent, is utilised to highlight the differences between the domestic past and the adventure (and danger) of the future. For instance, in War of the Worlds (1897), the loss of domesticity is signalled early in the novel when the narrator notes the objects “people had dropped — a clock, a slipper, a silver spoon and the like poor valuables” (Book 1, Chapter 12). Each dropped object hints at the destruction of the past era: the clock suggests that humanity’s time has come to an end; the slipper is a sign of the destruction of the home and hearth; and, finally, the silver spoon suggests that the values of the past — ideas of domestic practice, good manners, and class — have been discarded. Later in the text, the narrator meets with an artilleryman who tells the him that if he is concerned by a lack of “drawing-room manners or a dislike to eating peas with a knife” (Book 2, Chapter 7), he will not survive in the post-Martian world. In this conversation the artilleryman describes the new human order under the Martians — it is at this point that the narrator fully realises that domesticity and the fine manners of the past are over.

Late nineteenth-century fiction rewrites the man as an adventurer; no longer is he the domestic ruler concerned with the knives, forks, and spoons of the home, but, rather, he has become a man of action, living a life of danger and excitement. On the rare occasion that cutlery does creep into a novel, these items are used to recall the soft domestic ideas of the past, only to make clear that these are soon to vanish — perhaps forever.

References

- Broomfield, A. (2007). Food and Cooking in Victorian England: A History. Santa Barbara: Praeger.

- Tosh, J. (1999). The Flight from Domesticity. A Man’s Place. Connecticut: Yale University Press.

Please cite this blog post as follows: Jackson, K. (2019, July 26). The Decline and Fall of Cutlery and the Domestic Man [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2019/07/26/the-decline-and-fall-of-cutlery-and-the-domestic-man/

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?