To mark the launch of the African American Writers Corpus 1892-1912 (AAW; beta release), this guest post by Dr Jimmy Packham introduces one of the key authors of the AAW corpus, Charles W. Chesnutt. Jimmy is a Lecturer in North American Literature at the University of Birmingham and is a specialist in gothic fiction, including Chesnutt’s early writing.

Charles W. Chesnutt (1858-1932) is one of America’s major writers of the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries. He might readily be seen as a figure bridging the divide between a number of important literary movements from this period: from the substantial gothic tradition evoked by his early fiction, through local colour writing, into literary realism, and engaging at the end of his career with the emergent Harlem Renaissance, with whose activists and advocates he was politically aligned even as his own fiction was seen as old-fashioned and out-of-kilter with predominating trends in African-American writing.

Chesnutt maintained a career-long interest in the social standing of African-Americans in the US South in the wake of the Civil War and the failures of Reconstruction, and the particular modulations he gave to this interest developed alongside his experimentation with new literary modes. Chesnutt’s early gothic-tinged, dialect-heavy fiction—in work collected in The Conjure Woman (1899)—focused principally on the experience of African-Americans who continued to live in the vicinity of the plantations on which they were formerly enslaved, articulating their history through the ghosts and folktales bound-up with these spaces. Chesnutt’s second short-story collection, The Wife of His Youth and Other Stories of the Color Line (1900) and his realist novels moved away from the sites of slavery and turned greater attention to the specific experiences of African-Americans and mixed race individuals in a segregated South—The Marrow of Tradition (1901; now available in CLiC!), for instance, dealt with the rise of white supremacy and the 1898 race riot in Wilmington, North Carolina. (Chesnutt himself was seven-eighths white, but never chose to “pass” as anything other than African-American.)

In this way, we might consider Chesnutt’s interest in the particular forms and linguistics of certain genres as correlated to his developing socio-political interests, seeking new and more suitable forms to suit the particular stories he sought to tell: if a version of the gothic (inflected by an overtly black cultural tradition through the presence of conjure) was the appropriate vehicle to explore the haunting legacy and continued influence of slavery on the lives of those who had been enslaved, realism permitted Chesnutt to locate his critique of the treatment of African-Americans and mixed race people in a more immediate and recognisable time and space.

My research interests in Chesnutt stem foremost from his distinct interest in voice—not simply in the giving voice to groups of people he considered as silent (or silenced) in contemporary literature, but in the careful attention he paid to the representation and description of voice in his works, most significantly through his use of a black vernacular dialect, and further evident in his interest in characters with disorderly voices, in ghostly voices, and, indeed, in those with no voice at all. In Gothic Utterance—the monograph I am completing on voices in American gothic fiction—I argue that, in Chesnutt, storytelling acts as a vehicle for re-embodying, and finding an appropriate speaking subject for, the haunting and ghostly utterances of the dead or strangely metamorphosed slaves that feature in his most gothic tales. The digitisation of Chesnutt’s three major novels as part of CLiC gives us the opportunity to really get to grips with some of the most distinctive cadences of Chesnutt’s representation of voice and speech in his writing. To this end, CLiC should also prove a valuable teaching tool for those of us who read Chesnutt with our students on literature programmes: it allows students to dig into the texts in ways that can help highlight not simply who talks, but how they talk, and how frequently a particular kind of speech (such as dialect) is deployed, and how this compares with similar usage by his American and British contemporaries. An exploration, then, of the presence of dialect in Chesnutt is a good place to begin.

“weighted down with dialect writing”

The initial reception of Chesnutt’s dialect fiction—primarily those tales collected in The Conjure Woman—was positive. Chesnutt was entering into a literary tradition in which dialect so often signified a stereotype: the comic black figure as embodied in the writing of Joel Chandler Harris, who popularised the characters of Uncle Remus and Br’er Rabbit, and Thomas Nelson Page, whose fiction cast a nostalgic look back at the days of southern slavery. In 1899, the New York Mail and Express noted that theirs was an age whose “literature of all kinds is so weighted down with dialect writing” (quoted in Andrews, 1980: 44). Chesnutt’s dialect tales—and his protagonist, Uncle Julius—cuts back against the writing of Harris and Page, deliberately invoking the stereotype to invert or undermine it.

While many reviewers saw Chesnutt as making refreshing use of dialect, Chesnutt himself expressed a pronounced ambivalence towards it in letters from the 1880s and ’90s: “I think I have about used up the old Negro who serves as a mouthpiece, and I shall drop him in future stories, as well as much of the dialect writing” (quoted in Andrews, 1980: 207). Elsewhere, he emphasised that “the dialect story is one of the sort of Southern stories that make me feel it my duty to write a different sort” (H. M. Chesnutt, 1952: 107). As a result of this, Chesnutt’s novels—The House Behind the Cedars (1900), The Marrow of Tradition, and The Colonel’s Dream (1905)—all downplay the prominence of dialect. Nevertheless, running Chesnutt’s novels through CLiC’s keywords search function, with the “19th Century Reference Corpus” as a point of reference, words in dialect continue to feature among Chesnutt’s most common terms—ter (to), suh (sir), and de (the) among the most popular. When compared with the ‘African American Writers 1892-1912’ reference corpus, these dialect terms continue to figure prominently in his keywords. With more data—for instance, adding more late nineteenth century American fiction to the reference corpus—we might take these findings in one of two directions.

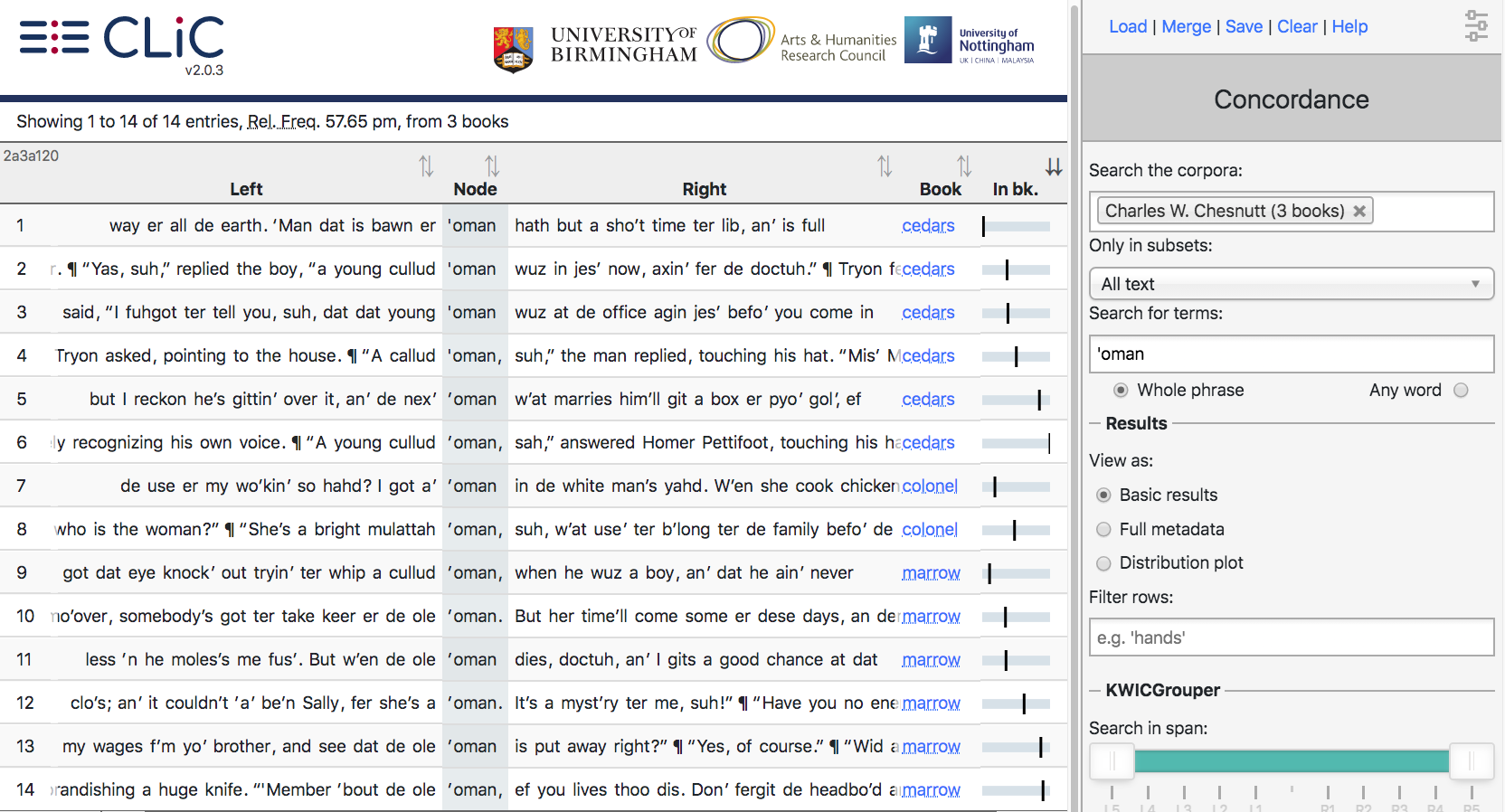

On the one hand, we can consider the importance that continues to attach itself to dialect in Chesnutt’s writing. On the other hand, we might think more broadly about the distinctive features of turn-of-the-century American writing and the place of dialect within this—another of the American books available in CLiC, Huckleberry Finn (1884), is (in)famous for its extended use of dialect and racialised language. It alerts us, too, to the explicit manner in which the markers not just of racial but of class difference heavily inform American writing of the period. Pushing further into Chesnutt’s use of dialogue, we might pursue the presence of a particularly distinctive term through his fiction. By using CLiC’s concordance function to search for a term such as ’oman (woman), we can see that, while Chesnutt seems to be making greater overall usage of dialect writing than many other nineteenth-century writers in the corpora, it appears concentrated in particular places throughout his writing (see Fig. 2). If a type of dialect is appearing in more self-contained sections of his novels, one hypothesis we can raise relates to the establishing of a distinctive site within the text or narrative for the voices of black or mixed race Americans. We might even think of the relationship between form and plot here: do these texts enact a kind of ‘segregation’ at the level of narrative form, echoing the social segregation that informs the action of the plot?

Chesnutt’s gothic voices

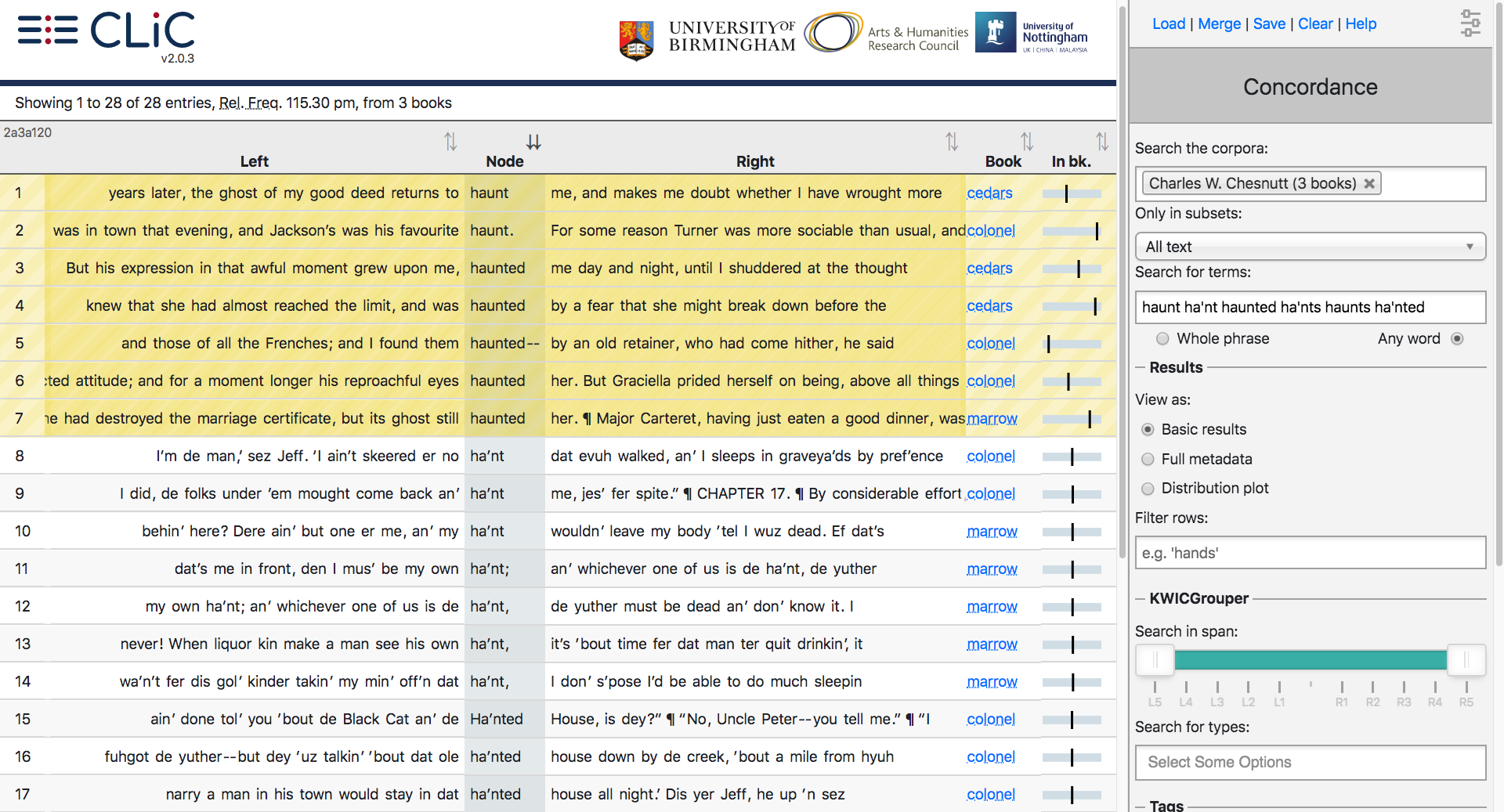

Finally, my own research on Chesnutt explores the gothic qualities of the voices of many of his characters—their haunted voices, their desire to tell ghost stories, and the ways in which voice and utterance function as sites and objects of haunting in their ghost stories. Even if Chesnutt abandons the gothic as a generic form in his long-form fiction, another concordance search on Chesnutt’s novels suggests the language of the gothic continues to operate in productive ways. For instance, a simple gothic term—haunt and haunted—reveals the two different ways in which gothic terminology is functioning in this writing (see Fig. 3). Haunt appears only twice and haunted five times across the three novels, and in every case it refers either to a favoured location—a favourite haunt—or to a figurative haunting, rather than an overtly supernatural occurrence. However, searching the dialect version of the terms—ha’nt and ha’nted—reveals not only its greater frequency but the fact that in every case it refers to the prospect of a supernatural, rather than figurative, haunting. As Uncle Peter explains in The Colonel’s Dream, ha’nts are “sperrits er dead folks, dat comes back an’ hangs roun’ whar dey use’ ter lib” (Chesnutt, 1905/2014: 217).

We might be attentive here to the specific notion of the ha’nt, as opposed to a haunt/ing, in a southern black tradition. The ha’nt that “hangs roun’ whar dey use’ ter lib” is a means to articulate a location associated with a particular trauma or traumatic event, and many of Chesnutt’s plantation tales use the ha’nt as a literalised metaphor for the ongoing traumas of slavery. As Andrew Silver (2006: 134) further notes, Chesnutt makes use of the ha’nt in order to “carve out areas of African American ownership within white spaces, providing a home for African American culture and empowerment”. This concordance search through Chesnutt’s novels, then, suggests the ways in which the writer is not simply finding a space for black or mixed race voices in his writing, but how, through his considered use of dialect terms like ha’nt, he is giving voice to a distinctive southern cultural tradition.

References

- Andrews, W. L. (1980). The Literary Career of Charles W. Chesnutt. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.

- Chesnutt, C. (1905/2014).The Colonel’s Dream, ed. by R. J. Ellis. Morgantown, WV: West Virginia University Press.

- Chesnutt, H. M. (1952). Charles Waddell Chesnutt: Pioneer of the Color Line. Chapel Hill, NC: University of North Carolina Press.

- Silver, A. (2006). Minstrelsy and Murder: The Crisis of Southern Humor, 1835-1925. Baton Rouge, LA: Louisiana State University Press.

Please cite this post as follows: Packham, J. (2019, October 14). Dialect and the dead: Charles W. Chesnutt and the voices of the US South [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2019/10/14/dialect-and-the-dead

Join the discussion

1 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?Comments