Fe Brewer is an English teacher and Lead Mentor in Leicester. She is the co-author of Succeeding as an English Teacher (Bloomsbury 2021) and blogs and presents on English subject knowledge and education. In this post, she explores how Dickens’ portrayal of children echoes contemporary changes around the concept of childhood.

Talk to young people across the country and – if they’ve ever studied Dickens – they’ll probably be able to tell you something about his childhood. ‘He worked in a factory’, ‘his dad went to prison’ and the like. While we often reference these biographical details as motivations for Dickens’ writing on the poor, we frequently neglect to consider what impact they may have had on his understanding and portrayal of childhood.

Dickens lived at a time when what it meant to be ‘a child’ was changing dramatically. When he was born in 1812, children and young people made up a significant portion of England’s workforce and there were very few restrictions or laws to regulate how or where children worked. In effect, most children were merely seen as small adults. This would have been painfully clear to Dickens, particularly in his pre-teens while working in a blacking factory and trapesing miles across London to visit his father and family in debtors’ gaol.

However, by the time Dickens had found his feet as a writer, and had his own children, the concept of childhood was changing. Far from being miniature adults, children were increasingly seen as something separate from adults, with their own needs and desires. We can see this clearly in the increasing laws around child labour, the growing discussion around children’s schooling, and the emerging market for children’s literature, namely fairy tales. In many ways, the concept of ‘childhood’ as we now know it, was created in the Victorian era.

A more well-known (but closely related) change in the era was the changing concept of Christmas. Both, in many ways, were ushered in unintentionally into public consciousness by the young Queen Victoria and her beloved Prince Albert having a growing family of royal babes – it’s worth noting that legitimate royal children hadn’t been on the scene for many years. Scenes of family Christmases orientated around children, tree-decorating and gift-giving gave Britain’s growing middle classes something to aspire to and recreate with their own families. Here, again, Dickens’ own life offers parallels to Queen Victoria’s: both had rapidly-growing brood of young children, and his increasing wealth meant he could easily adopt new Christmas traditions: sending cards, enjoying a goose, and buying toys for his children (another new trend tapping into an increasing middle-class market).

Dickens’ publishing of A Christmas Carol cannot be ignored in the development of what we now experience as ‘Christmas’. Dickens’ portrayal of Christmas scenes filled with laughter, games, snow, and the all-important family gathering with a goose so splendid its smell might make you delirious (see Stave 3; the Cratchits), Dickens’ images worked almost as a playbook for the masses. Importantly, children formed a large part of the idealised Christmas he created.

Dickens’ Language Around Children

As with Christmas, Dickens was a key driver and champion of the concept of children being separate from adults and being allowed a ‘childhood’. We can see this distinctly in the child characters he creates and invites us to both like and feel sorry for. Oliver Twist and Tiny Tim are, essentially, propaganda for Dickens’ concept of ‘the child’. They are both likeable children, but very vulnerable – two concepts that underpinned the newly emerging perspective of childhood in the nineteenth century.

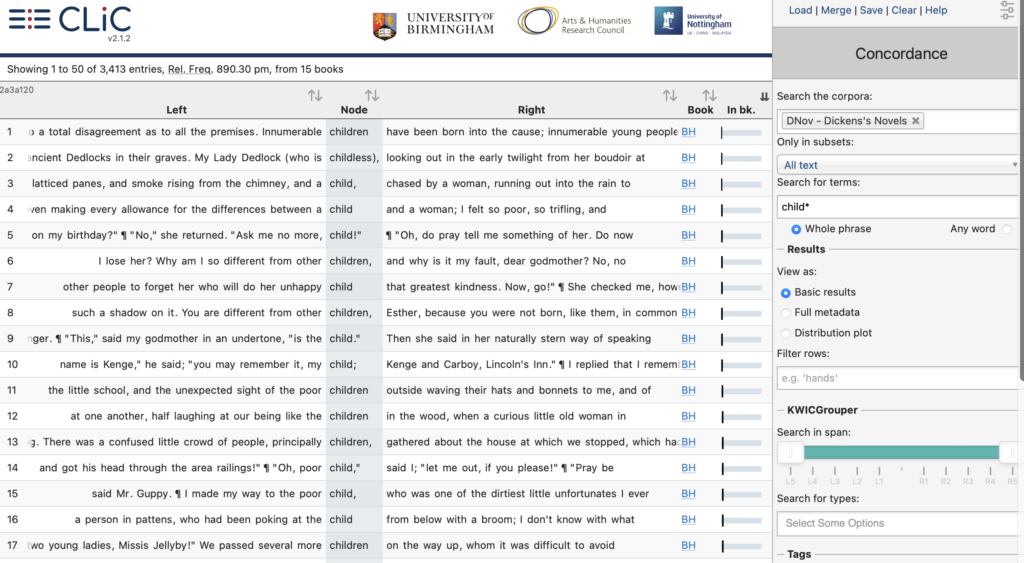

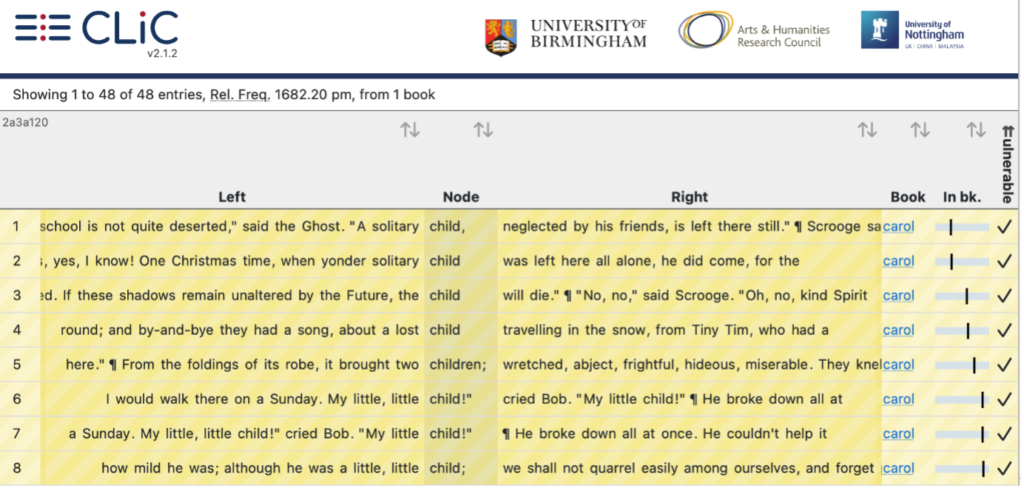

By using the CLiC Web App, (Mahlberg et al. 2020) we can see this through Dickens’ own words. If we run a concordance search for child* (using the * as a wildcard so as to find child and children), and look at the adjectives and phrasing around children, we can see patterns in the adjectives used by Dickens to describe children.

We have adjectives used to describe children who are vulnerable: ‘poor’ (Dickens uses this frequently), ‘mere’, ‘little’, ‘small’, ‘melancholy’, ‘overshadowed’, ‘meagre’. We also have adjectives that portray children as likeable: ‘perfect’, ‘likeable’, ‘dear’, ‘darling’, ‘innocent’, ‘sweet’.

Children in A Christmas Carol

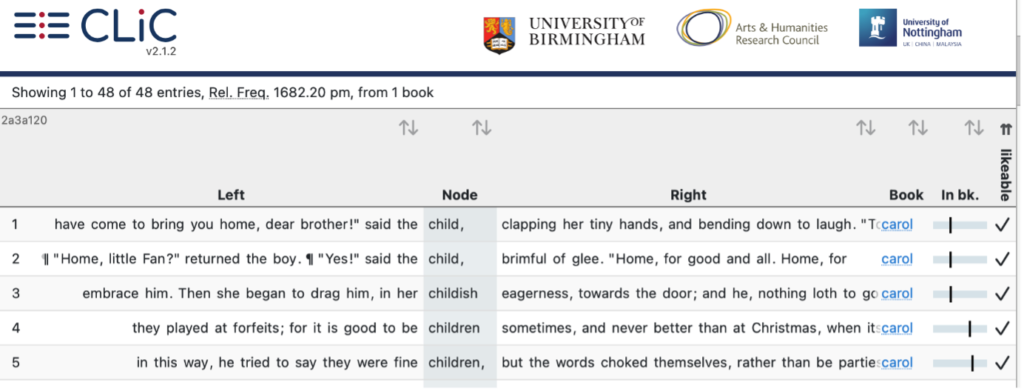

These patterns are even more clear when we focus on A Christmas Carol (1843). Searching child* in A Christmas Carol shows us that Dickens uses the word ‘child’ or ‘children’ 48 times throughout his novella. Given this is twice as often as ‘women/ woman’ and only 18 fewer than ‘man/s’ and ‘men’, we can see that children have a key role to play in the novella.

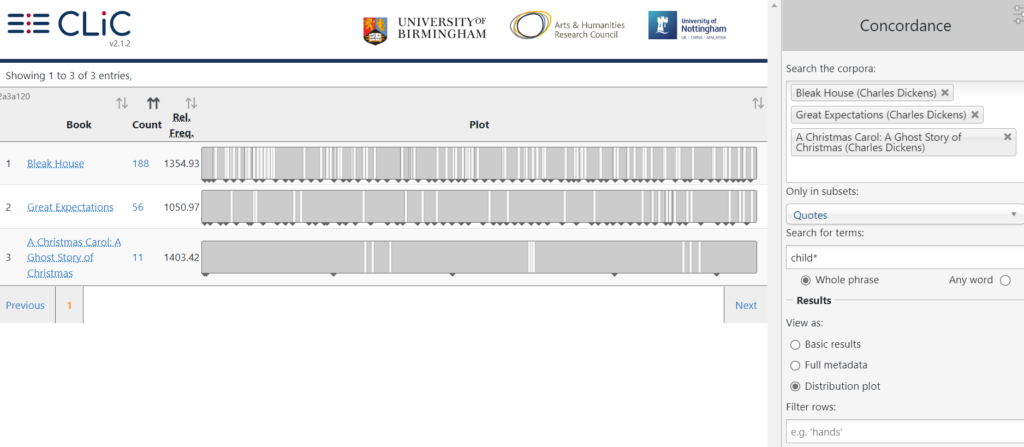

By selecting the Distribution plot feature, we can distinctly see that ‘child/ren’ appears in distinct sections in the novella: at times they are featured, and at times they are not. I found it interesting here, to select different works by Dickens and explore the distribution: while ‘child/ren’ appears frequently throughout Little Dorrit, David Copperfield and Bleak House, its use is far more pronounced in Oliver Twist and Great Expectations.

Focusing on the concordance lines in these novels, however, we can see two distinct patterns again:

Likeable children

Dickens creates his happy children through a range of different word classes: interestingly, when portraying children’s positive qualities, he only once uses an adjective before the word itself. Instead, his portrayal of their likeable qualities often comes after the noun: ‘child, brimful of glee’, ‘child, clapping her hands’; ‘childish eagerness’. In addition, he describes that it is ‘good to be children’, and remarks on some ‘fine children’.

Vulnerable Children

When portraying vulnerable children, Dickens offers different syntax and often places an adjective directly before the word: ‘solitary child’, ‘solitary child, neglected by his friends’, ‘lost child’, ‘little child’, and ‘little, little child’. The reason for this, we can speculate, may be to directly communicate the isolation and fragility of these children, perhaps. As we’d expect from Dickens – who does rather adore a list – he also couples ‘children’ with a list of adjectives when describing Ignorance and Want, the two skeletal children who cling to the cloak of the Ghost of Christmas Present. They are ‘wretched, abject, frightful, hideous, miserable’: for such powerful figures, a single adjective would not suffice.

These child characters are worthy of such a list: they serve as foils who distinctly contrast the joy and light of the other child characters – and the rest of the novella. Together, they embody the consequences of mankind’s actions; their hideousness is a direct result of the sins their names capture, and their youth represents the vulnerable future of man. In his description of them, Dickens indicates what children should be, but also reminds us how humanity’s greed and avarice (embodied by Scrooge) is directly destructive to our own future.

Where graceful youth should have filled their features out, and touched them with its freshest tints, a stale and shrivelled hand, like that of age, had pinched, and twisted them, and pulled them into shreds. Where angels might have sat enthroned, devils lurked, and glared out menacing.

(Stave III, A Christmas Carol)

The clauses at the start of each sentence connect childhood with the purity, grace, and health that Dickens portrays through his likeable children. By establishing this as the natural state of children, Dickens is able to ascribe anything less than vitality to mankind’s neglect and abuse, giving those with the power to take action against child poverty little room to make excuses.

Another child who is vulnerable is, of course, Tiny Tim. In contrast to Ignorance and Want, he has maintained his angelic features through the deep affections of his family. However, this is not enough to protect him from mankind’s neglect. In his speech, the Ghost of Christmas Present states to Scrooge that, if things do not change, ‘the child will die’. Dickens’ repeated use of ‘child’, —rather than naming Tiny Tim (‘you are more worthless and less fit to live than millions more like this poor man’s child’) — is a strategic choice. By referring to Tiny Tim as ‘child’ rather than individually naming him, Dickens positions him as one of many, rather than an exceptionally individual. Moreover, Dickens firmly portrays Scrooge, and his choices, as the key to Tiny Tim’s fate — a moment of allegory that directly associates the actions of the rich with the precarious mortality of the poor.

Concluding Remarks

Perhaps the most poignant instance of the word ‘child’ is this: ‘Bob held [Tiny Tim’s] withered hand in his as if he loved the child and wished to keep him by his side and dreaded that he might be taken from him.’ Here we have an intertwining of Dickens’ two concepts of childhood: a child that is vulnerable, but also valuable; who is loved but could be lost.

References

- Mahlberg, M., Stockwell, P., Wiegand, V. and Lentin, J. (2020) CLiC 2.1. Corpus Linguistics in Context, Available at: https://clic.bham.ac.uk/

- ‘Child Labour’. The National Archives Citizenship Exhibition, https://www.nationalarchives.gov.uk/pathways/citizenship/struggle_democracy/childlabour.htm#:~:text=Further%20legislation%20limiting%20child%20labour,such%20legislation%20was%20not%20foolproof. Accessed 31 July 2022.

- ‘Victorian Christmas Traditions’. English Heritage, https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/christmas/victorian-christmas-traditions/ Accessed 5 August 2022.

Please cite this post as follows: Brewer, F. (2022) Innocence and Ignorance: Concepts of Childhood Reflected in Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from [https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2022/08/08/childhoodaca/]

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?