Tiffany Olgun is a PhD student at Royal Holloway, University of London, researching the Dickensian dandy. In this post, she explores the language surrounding nineteenth-century English dandyism and the progression of the dandy from his Regency incarnation to his decadent form.

The nineteenth-century English dandy is often portrayed as a man of pure surface and exteriority, whose overdone appearance betrayed an interior that was the exact opposite: hollow and vacuous. The dandy was amoral with a sharp wit; he cut other dandies down in the street with his words and outshone his interlocutors. A stereotypical dandy did not engage in labour; he was a gambler and a gourmand, living and breathing the performance of dandyism until death or debt.

As clothes are vital to the creation of the dandy persona, I used the CLiC Web App (Mahlberg et al. 2020) to investigate clothing associated with the dandy, such as waistcoats and cravats — to piece together a fuller sartorial picture. This process was a part of my initial research for my PhD thesis, Dickens and Dandyism (ongoing).

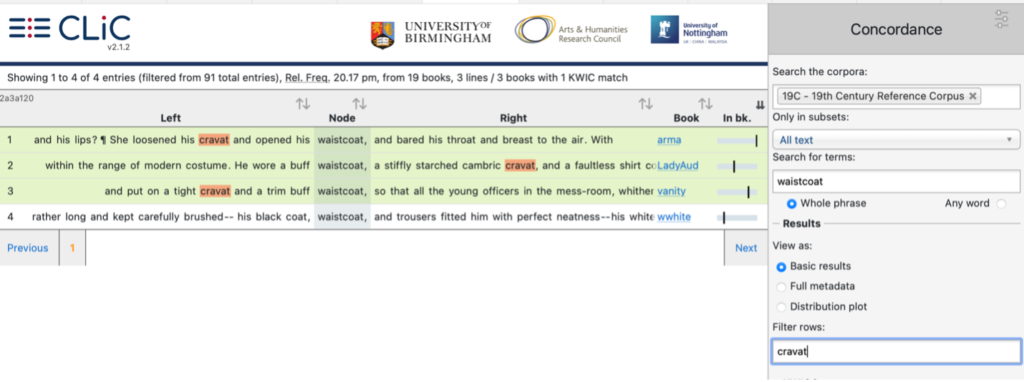

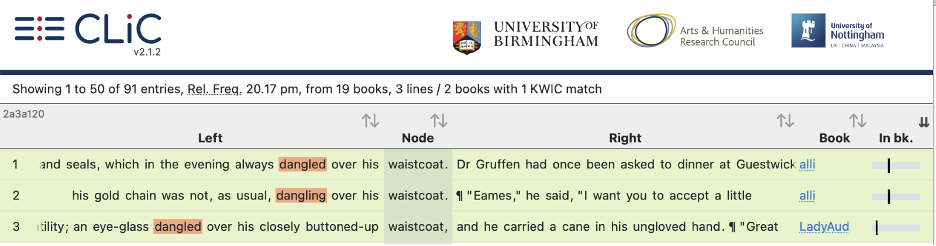

To begin, I ran a concordance search in CLiC’s Nineteenth-Century Reference Corpus, selected “all texts,” and searched for the term waistcoat. I then filtered the rows for “cravat” and other items of clothing that dandies were known to wear. In four instances, I found dandies attired in gold chains alongside a cravat and, in three instances, the gold chains were paired with a waistcoat. I noticed that the verb “dangle” popped up twice to describe the position of a chain or eyeglass in relation to a waistcoat. This verb serves to enhance the image of the dandy as lackadaisical, louche, loose in his morals, and bodily affected by ennui. I then searched dangle* (using CLiC’s * wildcard feature to also find dangles and dangled) with the term dandy.

This linguistic research helped me to develop more complex theories about the figure of the dandy surrounding the manner in which clothes control his signification through ‘sartorial speech’ (109).

Piecing Together the Nineteenth-Century Dandy

The accepted founding father of dandyism is George Bryan Brummell, more popularly known as Beau Brummell. He was not a born gentleman, but his family had enough money to send him to Eton and Oxford, where his penchant for fashion spread far and wide. The Prince Regent (later George IV) took note of him and visited his home to watch him dress, greatly elevating Brummell’s standing in society. Before long, he was made a member at many of London’s most exclusive clubs and soon his dress and lifestyle began to dictate both the dandy dress code as well as its behavioural one (Moers 26).

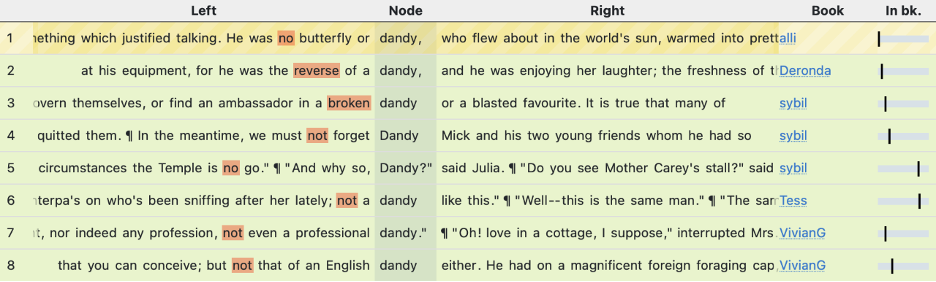

To further enhance my understanding of dandies and dandyism across the nineteenth century, I searched dandy in the Nineteenth-Century Reference Corpus and examined all the concordance lines in which the word appeared. This enabled me to corroborate the dandy’s literary image with the research I had found in nineteenth-century journals and across the critical field. The image produced was not a flattering one: the dandy reads as violent, vulgar, careless, impertinent, and without responsibility; one who exploited the newly elastic concept of the “gentleman” by dressing the part but behaving disgracefully. Two particularly useful results from CLiC came from William Makepeace Thackery’s Vanity Fair (1847).

“Cuff, on the contrary, was the great chief and dandy of the Swishtail Seminary. He smuggled wine. He fought the town-boys … He had a gold repeater; and took snuff … He had been to the Opera … He could knock you off forty Latin verses in an hour. He could make French poetry.” — Vanity Fair (1847)

This first quote reinforced the idea of the dandy that I had come to build through my research. The second passage, quoted below, introduced me to the idea of dandyism as linked to the East, — a decadent iteration of the dandy explored by Oscar Wilde through The Picture of Dorian Gray (1890) (Dorian visits opium dens, to name just one example). There is a need for the dandy to experience all things mysterious, exotic, and, in this particular case, veiled to Western eyes.

“Young Bedwin Sands, then an elegant dandy and Eastern traveller, was manager of the revels. An Eastern traveller was somebody in those days, and the adventurous Bedwin, who had published his quarto and passed some months under the tents in the desert, was a personage of no small importance. In his volume there were several pictures of Sands in various oriental costumes.” — Vanity Fair (1847)

The Dickensian Dandy

As my work centres mainly on the Dickensian dandy and Charles Dickens’ attitude towards dandyism, I ran a concordance search for dandy* in the Dickens Corpus. Though there are many dandies and dandy-like characters scattered across Dickens’s text, only Bleak House contains explicit mention of dandies or dandyism. The passage, however, is significant in that it is a narratorial interjection on behalf of Dickens.

Dandyism? There is no King George the Fourth now (more’s the pity) to set the dandy fashion; there are no clear-starched jack-towel neckcloths, no short-waisted coats, no false calves, no stays. There are no caricatures, now, of effeminate exquisites so arrayed, swooning in opera boxes with excess of delight and being revived by other dainty creatures poking long-necked scent-bottles at their noses. There is no beau whom it takes four men at once to shake into his buckskins, or who goes to see all the executions, or who is troubled with the self-reproach of having once consumed a pea. But is there dandyism in the brilliant and distinguished circle notwithstanding, dandyism of a more mischievous sort, that has got below the surface and is doing less harmless things than jack-towelling itself and stopping its own digestion, to which no rational person need particularly object? — Bleak House (1852)

It is long and accusatory: a tirade against the social consequences of dandyism. Mid-century dandyism, for Dickens, had gone beyond destroying the self: it also corrupted government, religion, philanthropy, and other institutions meant to uphold society. Dandyism is a parallel disease of the text – the other being smallpox – which, like any true infectious disease, had ‘got below the surface.’ Dickens thus noted a dangerous shift from Regency dandyism, parasitic but harmless as it mainly focused on clothes, to a more decadent kind. He feared that art had become uncoupled from ethics and that the dandy and the fashionable elite, longing to turn themselves into works of art, had become senseless to reality. Dickens further explored this state of complete artificiality through the Veneerings in Our Mutual Friend (1865), who dine in a room in which all the walls are mirrors. They are all surface and are the best representation of Dickens’s fear that surface would triumph over depth and that society would approach something akin to post-humanity. In this way, Dickens pre-empts the decadent dandy, who emerges later in the decade and is most famously known through The Picture of Dorian Gray.

The Butterfly

How pleasant, then, to be bound to no particular chairs and tables, but to sport like a butterfly among all the furniture on hire, and to flit from rosewood to mahogany, and from mahogany to walnut, and from this shape to that, as the humour took one! — Bleak House (1852)

A one Mr. Bailey is described in Fraser’s Magazine (1837) as follows:

“[a] Dandy of the butterfly order: he was a patron of bright colours — light-blue coats, coloured silk cravats, fancy waistcoats — and was a warm supporter of nankeen trousers.”

Flowers

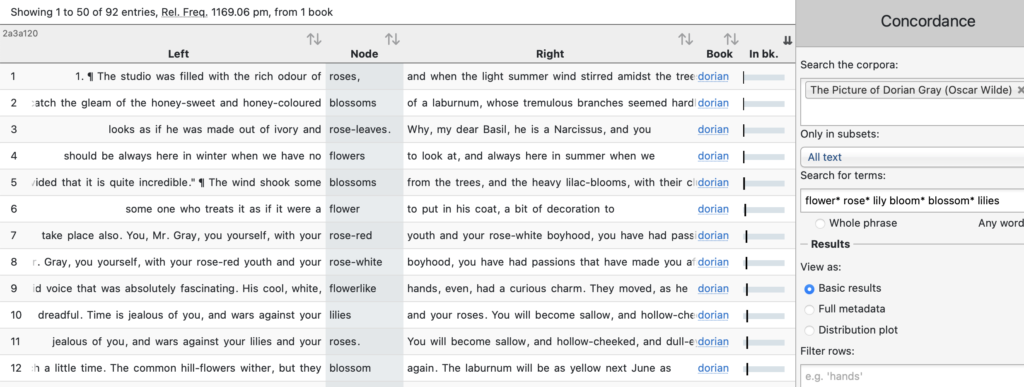

Oscar Wilde is also often connected to flowers. Like the butterfly, the flower is delicate and ephemeral, but it does not move. In its stillness, it is a living breathing work of art, much like Dorian Gray himself. As a concordance search shows, the pages of the novel are diffuse with the scent of flowers, all the stronger as they approach death and decay.

Oscar Wilde was famously known to wear a green carnation in his lapel, a symbol many understood as representative of his homosexuality. Because of the dandy’s rejection of women – he more so competed with them than for them – and also because of Oscar Wilde’s personal life, the dandy is often believed to harbor an interest in men. The stereotypical dandy typically rejects love as it is too messy (both physically and mentally) and causes one to be at the mercy of another. Dandyism, at its core, is entirely about the self: self-creation and self-performance.

Concluding Remarks

CLiC has been extremely useful in helping me find patterns amongst texts and to determine how similarly or dissimilarly different authors portrayed the nineteenth-century dandy, and to note how the descriptions of dandies changed as the years progressed. I did not have to read each and every silver-fork novel or fashionable novel to get the gist of what the dandy was like at this particular point in history.

References

- Dickens, Charles. Bleak House. Edited by George Ford and Sylvere Monod, W.W. Norton & Company, 1977.

- Evans, Brad. Ephemeral Bibelots: How an International Fad Buried American Modernism. John Hopkins University Press, 2019.

- Fraser’s Magazine for Town and Country, Volume 15, (1837).

- Mahlberg, M. Stockwell, P., Wiegand, V. and Lentin, J. (2020). CLiC 2.1. Corpus Linguistics in Context, Available at: https://clic.bham.ac.uk/

- Moers, Ellen. The Dandy: Brummell to Beerbohm. The Viking Press, 1960.

- Stanton, Domna C. The Aristocrat as Art. Columbia University Press, 1980.

- Thackery, William Makepeace. Vanity Fair. Penguin Classics, 2003.

Please cite this post as follows: Olgun, T. (2022) Decadence and Debauchery: Undressing the Dandy Using the CLiC Web App [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from [https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2022/09/17/dandyclic/]

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?