In this post, Marta Palandri (@hardlyanitgirl on Twitter) discusses the symbolism of windows, light and darkness in Bram Stoker’s Dracula. This post is part of the BMI Lockdown Life series, published in collaboration with the Birmingham & Midland Institute blog. Join the conversation at #BMILockDownLife.

“They simply seemed to fade into the rays of the moonlight and pass out through the window, for I could see outside the dim, shadowy forms for a moment before they entirely faded away.” (Stoker, 1997: 71)

As he first catches sight of Castle Dracula, Jonathan Harker’s first impression that he shares with the reader is rather claustrophobic; even from the carriage, he can see “a vast ruined castle, from whose tall black windows came no ray of light, and whose broken battlements showed a jagged line against the sky” (Stoker, 1997: 44).

The windows take up a central role even as the building first manifests itself in our imagination. And it is certainly no coincidence that, moving forward, the apparently insignificant windows become a symbol of particular significance throughout the book.

A lot of the main discoveries that Jonathan makes within the walls of the Count’s home begin with a window. The scene that sees Jonathan witnessing the Count climbing up the outside walls of his own mansion is among the most harrowing, as well as a defining moment for the narrator in the discovery of the very nature of the vampire. Images of windows paint a perfect picture of horror and discomfort throughout the whole novel, enriched by several elements of Gothic imagery.

The Castle as troubled self

The windows in Stoker’s work almost always appear in relation to Castle Dracula itself, and this is no irrelevant connection. The Castle is the place where the story begins and ends.

If we consider the Castle to be an example of a haunted mansion, we can as well consider it a vivid Gothic symbol, an entity that is alive, the mere look of which is troubling for its inhabitants (Aguirre, 1990: 92). It is very much so for Jonathan. The Castle meanders like a snake, its corridors and room inaccessible due to the sheer quantity of its corners. This distortion, so typical of the Gothic mansion, is a reflection of the natural self that aims at confusing the protagonist (Aguirre, 1990: 92), and can often be the beginning of an inward journey, not only within the house but also within the self. In this context the windows are, for the visitor, the only contact with the outside, a breach through the walls of insanity. However, whenever Jonathan looks outside, what he sees is consistently jarring.

Seemingly seeing horrors

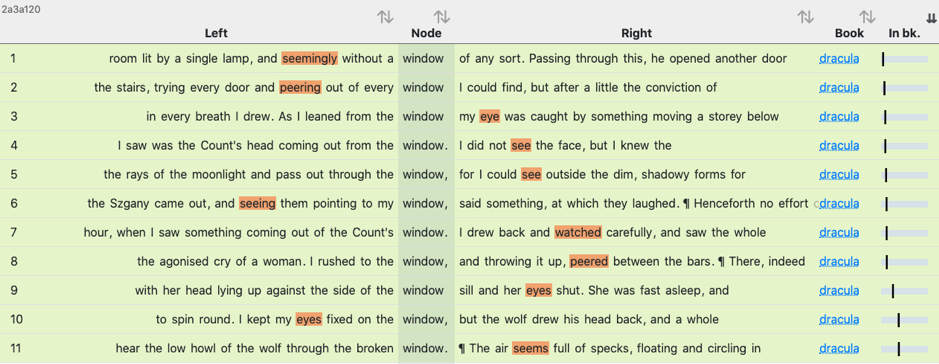

Creating a concordance with CLiC and searching for types using solely words that have to do with vision (seeing, eyes, peered, etc.), an interesting subgroup emerges. It is when a window is mentioned in relation to these words that the horror witnessed by our narrator truly comes to life. If the eyes are the mirror of the soul, they are in this case the reflection of a harrowing outside that shows itself to the viewer. The eyes are in this case the mirror of Jonathan’s soul on a deeper, rather primordial level, where the ugliness and madness of the inside projects themselves onto the outside. (On exploring eye language patterns with CLiC more generally, see Mahlberg et al., in press.)

The concordance in Figure 2 shows that Jonathan watches, peers, and his eyes are caught by all sorts of images that create a sense of confusion and contribute to the creation of what really catches the reader’s attention in Dracula (“…the stairs, trying every door and peering out of every window I could find, but after a little the conviction of…” in line 2, “…the Szgany came out, and seeing them pointing to my window, said something, at which they laughed.” in line 6, and “…with her head lying up against the side of the window sill and her eyes shut.” in line 9): not the vampire itself as much as his context, and what he represents of our very nature – the Uncanny:

“‘The Uncanny’ [implies] that the supernatural and madness are interchangeable, meaning that uncanny, supernatural phenomena and mental processes can be seen as directly related, even as the same thing” (Craig, 2012: 59).

One could say that the narrator’s realization goes in parallel with the development of his journey into madness provoked by his distressing discoveries.

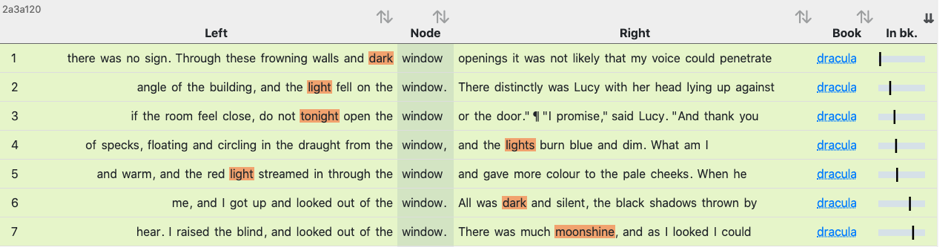

Light and darkness in the Castle

Interesting dichotomies emerge when looking at the data with yet a different choice of words. Images of darkness and light compose troubling scenarios through the use of the classic opposition of good and evil in the concordance lines shown in Figure 3: “Through these frowning walls and dark window openings it was not likely that my voice could penetrate…” (line 1), “…light fell on the window. There distinctly was Lucy with her head lying…” (line 2), “…the red light streamed in through the window and gave more colour to the pale cheeks.” (line 5), and “I got up and looked out of the window. All was dark and silent…” (line 6). (For an analysis of words related to light in Conrad’s Heart of Darkness, see Mastropierro’s post on this blog.) Confusion and madness versus sanity are once again protagonists of the narrator’s perception. It is the perennial battle between the real world and the fantastic and horrific, the agony of the individual trapped between two states of mind. The windows in the Count’s Castle become this way openings that allow sanity to come in in small doses to fight the darkness within. It is after all the prerogative of the Gothic novel to shed light onto the darkness surrounding the human state. The windows in Stoker’s Dracula are therefore not solely the eyes of the beholder of such horrors within a vampire’s home, but also a glimmer of hope that forces the narrator to take action against the evil that resides within the universal self.

References

- Aguirre, M. (1990). The Closed Space: Horror Literature and Western Symbolism. Manchester University Press.

- Craig, S. F. (2012). Ghosts of the mind: The supernatural and madness in Victorian Gothic Literature. Honors Theses. 99. https://aquila.usm.edu/honors_theses/99

- Mahlberg, M., Wiegand, V., & Hennessey, A. (in press). Eye language – body part collocations and textual contexts in the nineteenth-century novel. In L. Fesenmeier & I. Novakova (Eds.), Phraseology and Stylistics of Literary Language/Phraséologie et Stylistique de la Langue Littéraire (pp. 143–176). Peter Lang.

- Mastropierro, L. (2018, February 20). Is there light in the heart of darkness? [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2018/02/20/is-there-light-in-the-heart-of-darkness

- Stoker, B. (1997). Dracula. Edited by Glennis Byron. Broadview Press.

Suggested citation: Palandri, M. (2020, June). Looking through the windows in Stoker’s Dracula [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog.

Enjoyed this post? The Birmingham & Midland Institute has set up a fundraising campaign to “offset the income which would usually keep the BMI running as the social and cultural hub that it should be, and encourage you to donate to what is an important lifeline for many older people in our society.” Check out their fundraiser here.

This is a captivating exploration of the symbolism of windows in Stoker’s Dracula! Marta Palandri’s analysis beautifully highlights how windows serve as both literal and metaphorical thresholds between the known and the unknown. The connection between light and darkness through these openings adds a rich layer of meaning, illustrating Jonathan Harker’s internal struggle and descent into madness. I particularly appreciate the integration of Gothic imagery and the notion of windows as fragile links to sanity amidst chaos. This post not only deepens our understanding of Dracula but also invites us to reflect on the broader implications of perception and reality in Gothic literature. Great job!