Maya Sfeir (@mmsfeir on Twitter) is a Lecturer based in Beirut, Lebanon. Her research interests focus on examining and understanding the literary-linguistic interface. Her blog post was inspired by a conversation about Emily Brontë and anorexia that she had with one of the attendees of the Corpus Linguistics Summer School held at the University of Birmingham in June 2016.

In the satiric article “Every Meal in Wuthering Heights Ranked in Order of Sadness” published in 2016 on the (now-defunct) website The Toast, Daniel Mallory Ortberg described Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights (thereafter WH) as revolving around “a group of people who eat the most miserable meals imaginable, and cannot experience love as a result”. Ortberg amusingly added that “[s]ometimes [the characters] have tea, but more often they are merely offered it, and decide they are too furious to have tea, and die instead”. Ortberg’s humorous and witty comment was not the first to successfully capture the dynamics of (renouncing) eating and drinking in WH—though it remains perhaps the most comical and least scholarly. In fact, numerous academic articles have commented on eating and drinking in Emily Brontë’s gothic romance—contrary to Graeme Tytler’s (2009) claim that “little critical response” is available on food consumption in the novel (p. 57). Almost forty years ago, in their foundational work The Madwoman in the Attic, literary critics Sandra Gilbert and Susan Gubar (1979/2000) traced the powerful images of devouring and starvation in the novel. Some years later, Giulianna Giobbi (1997) argued that Catherine’s anorexia and self-starvation are means to defy patriarchy. Tytler (2009) himself traced the symbolic and psychological significance of the different types of foods and drinks mentioned in the novel.

Keywords

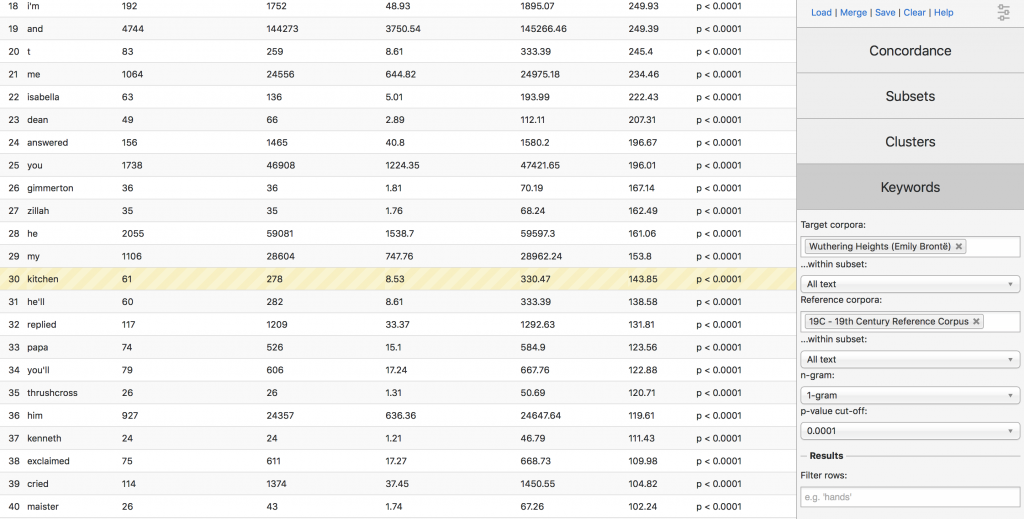

To begin with, an elementary keyword analysis reveals that the kitchen, like the heights and the grange, is a central space in WH. Keywords are by definition words whose occurrence in a text is statistically significantly higher than their occurrence in another reference corpus. Examining keywords can thus bring to light some of the main themes of a literary text and as such can serve as a point of departure for literary analyses (Fischer-Starcke, 2010, p. 65). To analyze keywords in the novel, I selected WH as the target corpus and the 19th Century Reference Corpus (19C) as a reference corpus. Of course, some scholars might disagree with the selection of 19C as a reference corpus given that it also contains WH. However, as Mike Scott and Christopher Tribble (2006) pointed out, “while the choice of reference corpus is important, above a certain size, the procedure throws up a robust core of [keywords] whichever the reference corpus used” (p. 64). In other words, some keywords are constant regardless of the selected reference corpus. I tested the keyword function by choosing the different corpora available on CLiC as a reference corpus: Dickens’s Novels (DNov), 19th Century Children’s Literature Corpus (ChiLit), or Additional Requested Texts (ArTs). The keywords (and later on, key clusters) I discuss in this blog post are common whether 19C, DNov, ChiLit, or ArTs is used as a reference corpus.

Results indicate that the word kitchen is one of the keywords in WH, occurring 61 times in the novel, almost seven times more than expected (see Figure 2). Significantly, the dominance of the kitchen as a space has been briefly described in two of the literary studies that commented on eating and drinking in Brontë’s text. For Graeme Tytler (2009), the kitchen in both the Heights and the Grange has different functions as a servants’ chamber and as a place of punishment and refuge, among others. Tytler also highlighted the fact that some of the novel’s most important scenes take place in the kitchen. In this respect, Gilbert and Gubar (1979/2000) pointed out that it is not a coincidence that Edgar and Heathcliff’s confrontation takes place in the kitchen. Their claims can further be supported by an examination of key clusters in WH.

Key Clusters

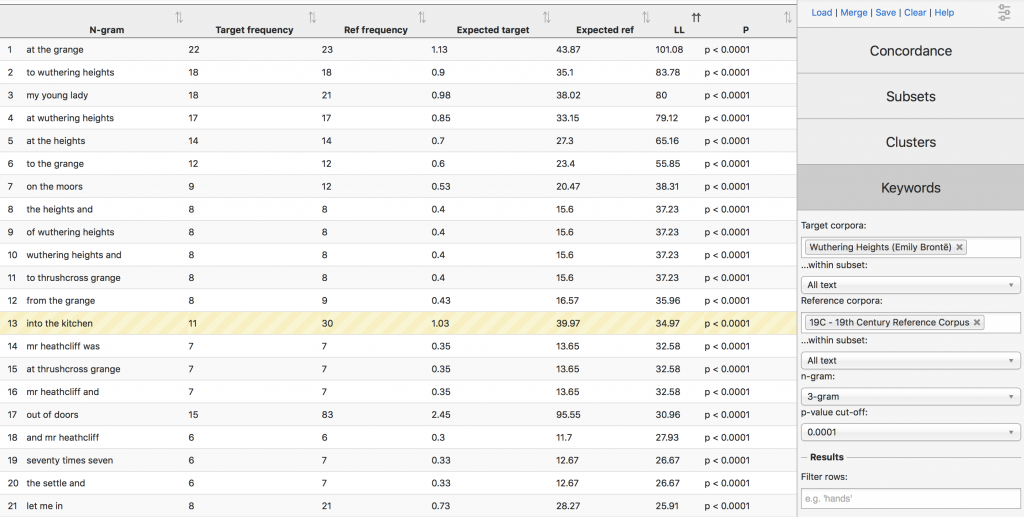

Key clusters in WH also demonstrate the importance of the kitchen. Key clusters are groups of words or phrases that are statistically more salient in a text as compared to a reference corpus. Because WH has a limited number of five-word key clusters, I mainly focused on three-word clusters that emerge when comparing WH to 19C (see Mahlberg (2013, pp. 71-72) for a comparison of the number of five-word clusters across 29 nineteenth-century texts, including WH). The list of three-word key clusters for WH has an abundance of what Mahlberg (2013) called ‘Time and place clusters’ (p. 67). Of these, the key clusters into the kitchen (f=11), of the kitchen (f=7), and in the kitchen (f=10) are of interest to my analysis (see Figure 3). Three of the seven occurrences of the cluster of the kitchen are preceded by out. Hence, we can conclude that being in, moving towards, and moving away from the kitchen space are part of the characters’ dynamics in WH.

Concordances

Concordances of the word kitchen show that characters frequently enter, leave, and pass through the kitchen. I used the “Manage tag columns” function to classify concordance lines pertaining to the word kitchen. Of the 61 occurrences of kitchen in the text, 38 denote a movement towards, out of, in, or across the kitchen. This motion around the kitchen space sets WH apart from other novels by the Brontë sisters, as I will later explain. Like keywords, key clusters and concordances thus offer concrete evidence for the arguments made by literary critics, in particular Tytler’s (2009) claim that characters make their “exits or entrances” through the kitchen (p. 57). As such, while literary critics did underline the prominence of the kitchen space in WH based on their own reading of the novel, using CLiC for corpus analysis has provided empirical textual evidence on the significance of the kitchen space.

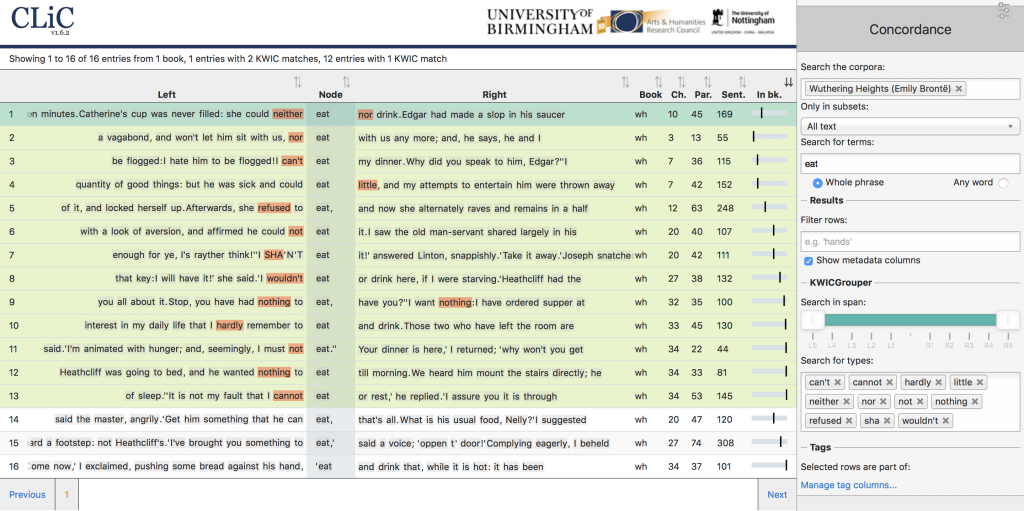

Investigating concordance lines of the words eat and drink sheds light on the significance of eating and drinking—or rather not eating and drinking—in WH. A simple concordance analysis of the verb eat in the present tense showed that out of the 16 occurrences of the verb, 13 are associated with negatives or scarcity (see Figure 4). The KWICGrouper function was used to highlight these negatives. Analyzing concordances of the word drink similarly revealed that seven out of the 14 instances are in the negative. These findings are notable because they add a new dimension to literary analyses of eating and drinking in WH. While the different literary articles on eating and drinking confirmed that the novel is replete with the “all-pervasive motif of self-starvation” (Gilbert & Gubar, 1979/2000, p. 282), and many main characters “abstain from food” (Tytler, 2009, p. 63), none of them pointed out that a vast majority of the occurrences of the verb eat and at least half of the occurrences of the verb drink in the present tense are linked to negatives.

Comparability

A main advantage of CLiC is that researchers can use it to compare their findings to other literary works. I thus examined concordances of the words kitchen, eat, and drink in other novels by the Brontë sisters that were available on CLiC Dickens: Charlotte Brontë’s Jane Eyre and The Professor, and Anne Brontë’s Agnes Grey and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall. When I inspected concordance lines of the word kitchen (f=28) in Jane Eyre, for instance, I noticed primarily a movement towards the kitchen and a presence in it (f=13). However, in The Professor, Agnes Grey, and The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, the kitchen is of no particular importance. Additionally, the verb eat occurs 26 times in Jane Eyre, but only 12—a bit less than half—denote refusal or unwillingness to eat. In The Tenant of Wildfell Hall, the verb drink occurs 16 times as noun and verb, a fact which is not surprising given that drinking problems are at the very heart of the work. [Editorial note: When comparing frequencies across different texts, it is best to use relative frequencies; this will be part of a future release in the CLiC development pipeline.] Thus, the same procedure used to examine kitchens, eating, and drinking in WH can thus be replicated on other works available on CLiC.

Conclusion

In this blog post, I have shown how CLiC can be used not only to reinforce but also to extend literary claims made by literary critics concerning (not) eating and drinking in WH. In particular, I have shown how a simple analysis of keywords, key clusters, and concordances reveals how the kitchen space dominates WH. My analysis has not only confirmed the findings of literary critics that the kitchen is important to the novel and that characters frequently enter and exit it, but has also revealed that the way characters move around the kitchen space in WH sets it apart from other Brontë novels. While readers and scholars might assume that the action in WH develops in the heights, the moors, and the outdoors, my analysis has shown that the interior domestic kitchen space is crucial. Likewise, while readers and literary critics have noticed that characters rarely eat or drink in the novel, my analysis has shown that, indeed, the verbs eat and drink are associated with negatives and scarcity. As such, a corpus analysis enhances our ways of reading and analyzing nineteenth-century novels and stories. Not only can a tool like CLiC confirm previous literary claims, but it also increases their comparability and paves the way for making new literary and linguistic claims.

Please cite this post as follows: Sfeir, M. (2018, May 18). On Kitchens, Keywords, Key Clusters, and Concordances: Re-examining Eating and Drinking in Emily Brontë’s Wuthering Heights [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2018/05/18/on-kitchens-keywords-key-clusters-and-concordances

References

- Fischer-Starcke, B. (2010). Corpus linguistics in literary analysis: Jane Austen and her contemporaries. London, England: Continuum.

- Gilbert, S., & Gubar, S. (2000). The madwoman in the attic: The woman writer and the nineteenth-century literary imagination. New Have, CT: Yale University Press.

- Giobbi, G. (1997). ‘No bread will feed my hungry soul’: Anorexic heroines in female fiction – from the example of Emily Brontë; as mirrored by Anita Brookner, Gianna Schelotto and Alessandra Arachi [PDF, 1200KB]. Journal of European Studies, 27, 73-92.

- Mahlberg, M. (2013). Corpus stylistics and Dickens’s fiction. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Ortberg, M. (2016, March 22). Every meal in Wuthering Heights ranked in order of sadness. The Toast.

- Scott, M., & Tribble, C. (2006). Textual patterns: Keyword and corpus analysis in language education. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Benjamins.

- Tytler, G. (2009). Eating and drinking in Wuthering Heights. Brontë Studies, 34(1), 57-66. Doi: 10.1179/147489309X427877

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?