In this guest post teacher Claire Stoneman shares her passion for Victorian literature with a case study of servants and agency in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. She emphasises the role of doors in this context – reiterating the importance of doors in this novella, which our Blog readers may remember from Lorraine Adriano’s earlier post.

Claire Stoneman (@stoneman_claire) is a deputy head of a secondary academy in Birmingham, UK. She also teaches English, and has a particular interest in Victorian literature. Claire is a member of the steering group for the Midlands Knowledge Schools Hub, and also works with a grassroots organisation – researchED – to promote the use of research-informed teaching and leading in education. Claire organises an annual regional conference with researchED: researchED Brum. She also likes design, particularly Modernism and Brutalism, and is partial to singing opera.

Teaching beyond the test

One of the areas in education I am most passionate about is teachers relishing, and having time to consider, the delicious specificity of our subjects. Returning to a personally crafted subject tabernacle – the most sacred part of what we love about what we studied at university. If, for whatever reason, we aren’t able to do this, if essentially we only ‘teach to the test’ as we may have done (or indeed may still do), we limit our pupils to “learning around the surface features of the test” (Counsell, 2018). And not only that – we limit ourselves to a life of little subject exhilaration. And who wants that dry husk of a life? We are all experts. We know the joy of our subjects, and the excitement of the specific areas of our subjects that give us full-on life-affirming joy: whether that be the Wars of the Roses, algebra, German lied. And we feel it keenly. Mine is Victorian literature. So this blog post has given me an opportunity to return to that, not in terms of lesson planning, or even in curriculum mapping, necessarily.

Although The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is a GCSE English Literature text, I would return to it anyway like an old friend; it’s a novella I read and loved a long time before I taught it. Initially this blog seemed to me an indulgence; I felt like I ought to be spending time writing something I initially saw as more productive: something more directly linked to an action in the classroom, or a resource, or a plan. But this blog post is a resource in itself, and writing it has made me afford myself the time and the space to reflect, think, and sew my patchwork of ideas together, whilst also giving me much food for thought for when I next teach the novella. Giving time for that subject-joy and subject-thought makes us better teachers, of that I’m convinced.

The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and My Hyde (1886) is a meandering novella, with complex, interwoven passages and bystreets, doors and windows, keys and locks. What I intend to do here is explore tentatively, through my emergent understanding of how to use CLiC (and I am no expert in corpus stylistics!), how servants in the novella are the gatekeepers, the signposters, the unlockers. It is they who move the narrative on; it is they who light the labyrinthine way. There are nearly as many shadowy ‘domestics’ in the novella as there are characters of higher social class: Poole, the maidservant who witnesses the death of Sir Danvers Carew, Lanyon’s butler, Hyde’s female maidservant, and the concerned gathering of servants in Jekyll’s house before Poole and Utterson break down the laboratory door. I am fascinated by the near-invisible proliferation of servants in the novella, and how it could be argued that they represent a fear of the supernatural, or indeed that this ‘supernatural’ symbolises a class-based fear of transition or movement from one social class to another as they invisibly move from house to house, door to door, lock to lock. The servants’ agency represents social leakage and transition.

Some of this is also apparent in, for example, Henry James’s The Turn of the Screw (1898). Although in this novella the Governess only has fragments of language and remnants of memory from Mrs Grose, she actively pieces them together to form her own elliptical narrative about Peter Quint, Miss Jessel, Flora and Miles. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde is different. In this novella, the servants have agency, and my analysis so far has shown they have far more agency than the characters of higher social class. I am interested in how servants are located in very close proximity to those of a higher social class, and how in this novella, they enable the mystery to be understood and unveiled. Utterson, without Poole, is adrift. On his walks with Enfield, Utterson “rambles” (p.6) off course into the “dingy neighbourhood” of Soho (p.6), and is, quite literally, lost. Later in the novella, on another ramble with Enfield, the tempting bystreet leads them to “gaze” (p.35) on the door, but they remain outside. It is the servants who guide, who open the doors, who admit visitors. It is the servants who are the signposts. There is almost an audacity to the servants’, particularly Poole’s, gatekeeping in the novella.

Doors – and who opens them

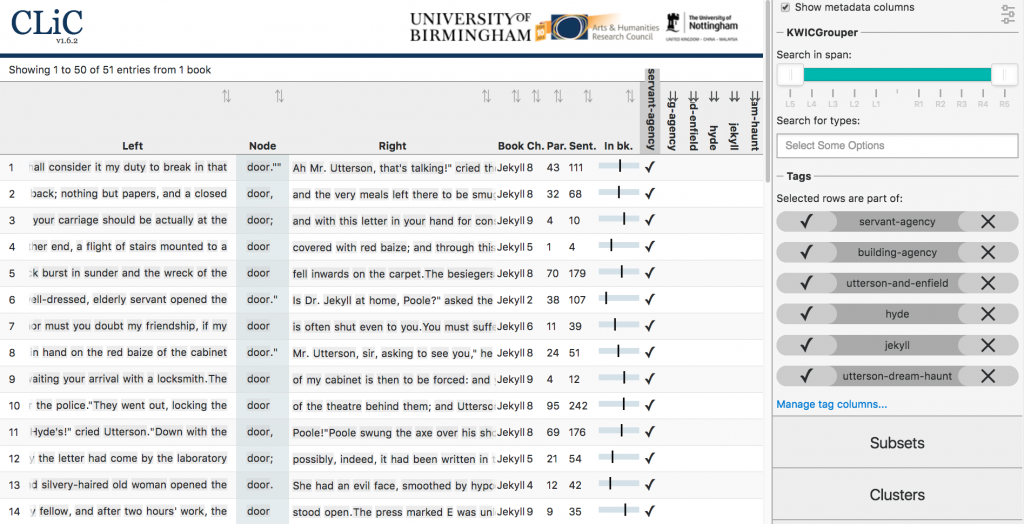

In the screenshot below, I used the ‘tag’ function[1] in CLiC to label the rows. My labels were linked to the context of the door in the sentence, and were as follows:

- Building agency

- Servant agency

- Utterson and Enfield

- Utterson dreams haunts

- Hyde

- Jekyll

It is worth me explaining why I chose these tags. Readers familiar with the novella will know that Hyde’s house is an actively malevolent presence in Chapter 1. Even the verb thrust (“…thrust forwards its gable on the street.” p.6) suggests Hyde, through the building, is actively forcing himself upon London. By the very stamp of the building on the street, Hyde is an imposition, a threat. The door of his house, though, is interestingly a shelter to those from the lower classes, or those without power: “Tramps”, children, the mark of a “school-boy” and other nebulous “random visitors” (p.6). But they only mark the door, and they do not remain. It is the servants who open doors, and remain, in the novella.

So my rationale for the above is that there are specific places in the novella where the building itself seems to have active agency linked to doors, whether it’s Hyde’s door with “neither bell nor knocker” (p.6) or the red baize door of Jekyll’s laboratory. I wanted to identify the context for other instances where doors are mentioned, and analyse the opening, closing, or partial opening or partial closing at that point. My second tag – servant agency – is linked to the many, many instances in the novella where servants open, close or break doors, usher characters through doors, direct characters through doors, or deny other characters entry. I used two tags for Utterson and doors: one with Enfield, and the other where Utterson either dreams about entry, or “haunt(s)” (p.14) Hyde’s door. The final two tags are for instances where Hyde is explicitly linked to a door or where Jekyll is explicitly linked to a door.

My initial examination of the noun door yielded fascinating results. As I thought, most of the occurrences of door at the very start of the novella were initially linked to the building (so, it could be argued, Hyde), and then to Utterson, and partially Enfield. But certainly from Chapter 5 onwards, it is the servants who open doors, close doors, refuse entry (some under their master’s orders, some not). Even in Chapter 8, when Utterson has decided he will break down Jekyll’s laboratory door, he only does so after the encouragement of the butler, Poole. In terms of the frequency of the noun door linked to the tags, here are the results:

- Building agency – 5

- Servant agency – 25

- Utterson and Enfield – 9

- Hyde – 7

- Utterson only (dreams, haunts) – 2

- Jekyll – 3

49% of references to doors in the novella are linked to active servant agency. In a further analysis I will look in detail at the verbs used by Stevenson to illustrate how servants move and act at instances involving doors – these points of transition – and how they demonstrate both control and lack of control. They convey a fear or acknowledgement of social leakage, and that the middle or upper-middle class home was not safe from the ‘supernatural’ agency of the servant.

Thank you for reading. I hope this has been of some interest to you.

References

- Adriano, L. (2018, March 5). CLiC in the Classroom [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2018/03/05/clic-in-the-classroom/

- Counsell, C. (2018, April 12) Senior Curriculum Leadership 1: The indirect manifestation of knowledge: (B) final performance as deceiver and guide [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://thedignityofthethingblog.wordpress.com/2018/04/12/senior-curriculum-leadership-1-the-indirect-manifestation-of-knowledge-b-final-performance-as-deceiver-and-guide/

- James, H. (2011) [1898]. The Turn of the Screw. London: Penguin.

- Stevenson, R. L. (2002) [1886]. The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde. London: Penguin.

[1] By adding tags to concordance lines, you can keep track of your analysis of individual lines and also sort the concordance on the tags you have used. For step-by-step exemplification of how to create tags, see the CLiC Activity Book on ‘user-defined tags’.

***

Please cite this post as follows: Stoneman, C. (2018, June 8). Signposting and gatekeeping the supernatural: Servants and doors in The Strange Case of Dr Jekyll and Mr Hyde [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2018/06/08/signposting-and-gatekeeping-the-supernatural

If you would like to join the conversation please feel free to leave a comment below. Perhaps this post has inspired you to write a post yourself? We are always happy to consider guest posts for the CLiC Dickens Blog; please refer to our simple guidelines and get in touch via Email or Twitter.

Really enjoyed this and am inspired to begin my own research.

To extend your ideas of social leakage, might we also argue that the lower messes are presented as having greater freedom to cross the boundary between good and evil, between their super ego and their Id? As having more awareness of what lies on the other side of morality since they (a) are thrust into more evil realms through their poverty and (b) less repressed than their wealthy counterparts?

Is there a certain degree of envy towards the lower class servant and resentment towards this power reversal, where the higher classes must beg support / assistance from the LC gatekeeper, since the world of animal instincts belongs to them, where survival is more reliant on primal instinct?

Now you have highlighted the prevalence of the servants at the door, I can’t help but see parallels with the Macbeth Porter at hell’s gate. Love this!