In this guest post, Sophie Phelps explores ‘liminal’ Dickensian characters who are not quite children and not quite adults, as she shows with a case study of David Copperfield’s “child-wife” Dora. We think this topic is a fantastic fit for us: questions of characterisation in Dickens’s writing are very dear to the CLiC project. Childhood is also an important theme, as our sister project GLARE investigates the representation of gender in the Corpus of 19th Century Literature (ChiLit), also hosted by CLiC.

Charles Dickens is not an author known for his simplicity. His novels are extremely overpopulated; they are practically bursting at the seams with characters and subplots. I knew I wanted to explore the depths of Dickens’s novels in my PhD, and it quickly became apparent to me that liminality was going to play a significant part in my research. It didn’t seem to matter which novel I picked up, they all included characters that appeared to be caught somewhere in between an adult and a child; they were liminal.

There had to be a reason that these characters were there. Once I had a focal point, I was able to refine my ideas, and this lead to one question: what is the purpose of these characters? From early works such as Oliver Twist (1837-9) with the Artful Dodger who “had about him all the airs and manners of a man” (ch.8, p.66), to much later works such as Our Mutual Friend (1864-5), with Jenny Wren who is a “child in years […] woman in self-reliance and trial” (bk.3, ch.2, p.439), these characters appeared. And it’s not just premature departures from childhood, who can forget the array of adult characters that never achieve maturity – the kindly Mr Dick in David Copperfield (1849-50) for example, or the maddeningly childlike Dora Spenlow in the same novel. The more I studied these characters the clearer it became; liminality signifies subtext. This wasn’t just a trait of Dickens’s writing, it was a narrative technique. He used liminal characters as a way to engage with subject matters that could not so easily be addressed on the surface of the text.

Let’s consider Dora Spenlow. In her book, The Awkward Age in Women’s Popular Fiction, 1850-1900: Girls and the Transition to Womanhood (2004), Sarah Bilston describes Dora as “the notorious child-wife of David Copperfield [who] provided a model of arrested growth and permanent immaturity” (p.47). This is not the first time Dora has received bad press. In her 1963 article for The Dickensian entitled “Child-wives of Dickens”, Jane W. Stedman writes:

In general, Dickens’s child-wives (including such diverse characters as Marcy Pecksniff and Bella Wilfer as well as the archetype Dora Spenlow Copperfield) are pretty, artless, innocent girls, varying in their degrees of unfitness to cope with adult life, but invariably charming (p.113).

Stedman goes on to explain, “Dickens seems frequently to equate innocence with impracticality, intellectual or emotional immaturity, and sexlessness” (p.115). Stedman is right of course, Dora is completely unfit for adult life, but it is Dora’s self-awareness regarding her liminality that I find most interesting, and this is where the CLiC web app became extremely useful.

Concordancing the child-wife

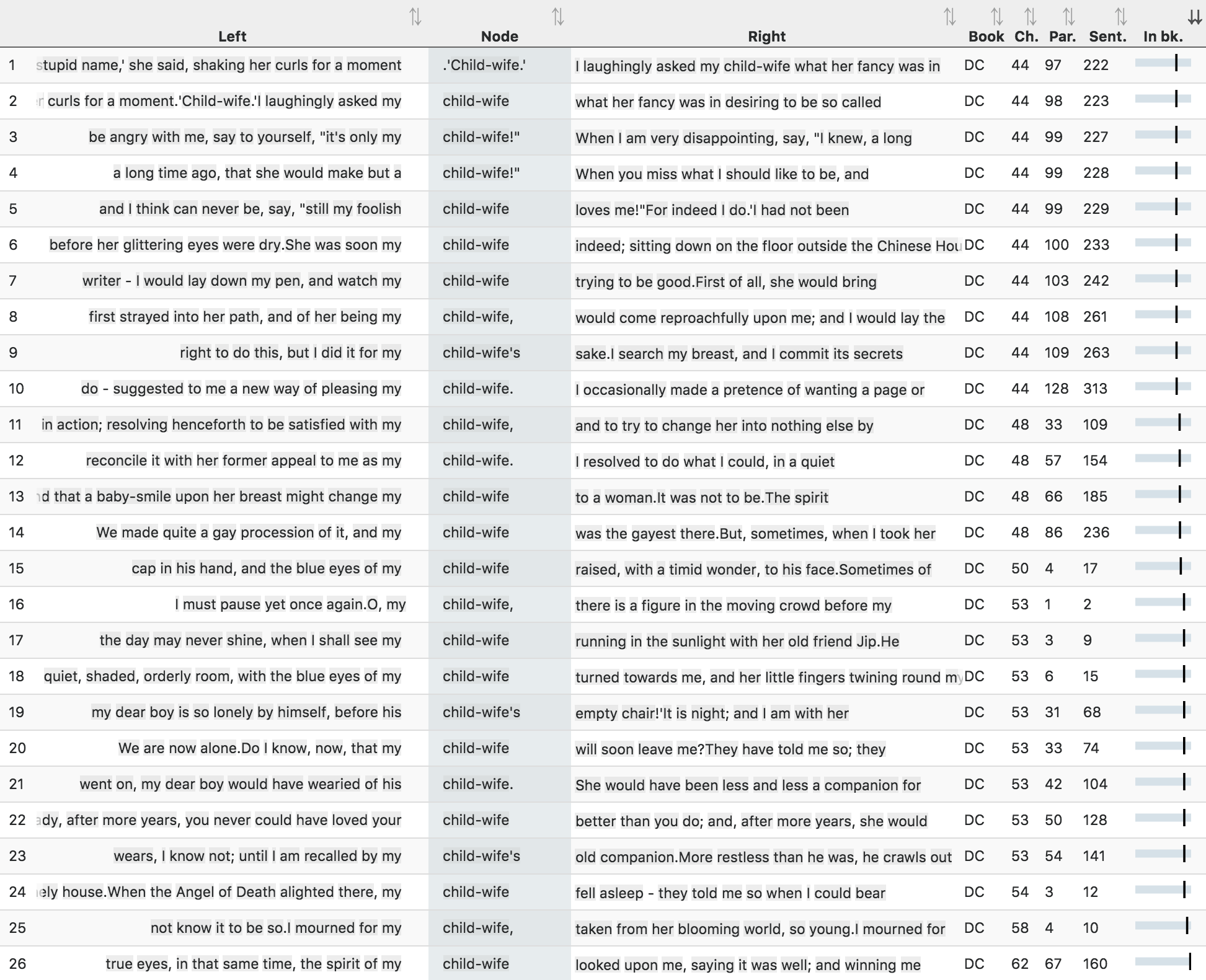

A concordance search for “child-wife” reveals a frequency of 26 instances in David Copperfield, 10 of which appear in Chapter 44 alone (see Figure 1). The concentrated frequency in particular chapters indicated that this phrase was extremely important at certain points during the novel, but I wanted to take this analysis further.

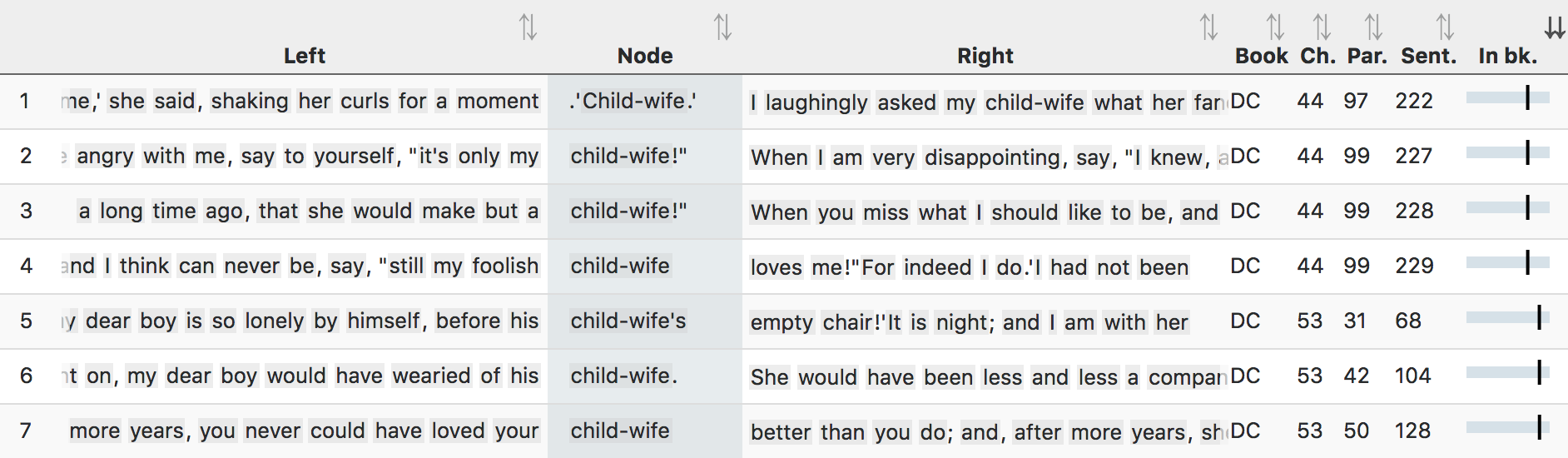

What I wanted to know was how many times Dora used the phrase herself. In order to do this, I changed the subset to “Quotes” and it revealed the concordance shown in Figure 2.

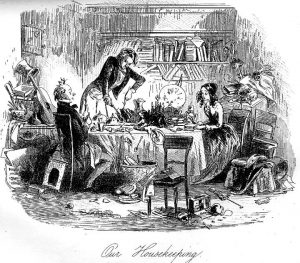

No less than seven times does Dora refer to herself as a “child-wife” throughout the novel, and again the phrase appears most frequently in Chapter 44. What this search revealed to me was that in order to fully understand Dora’s liminality, I needed to focus my attention on this chapter in particular; because it is at this point in the novel that Dora is most desperate for David to acknowledge her liminality. She is painfully aware that she has not transitioned into an adult, despite assuming the role of his wife, and therefore, being acknowledged as liminal validates her inability to cope with adult life. The illustration by Phiz in Chapter 44 of David and Dora in their marital home further highlights the discomfort Dora feels at being inadequate.

The chaos of the marital home is portrayed to the extreme in this illustration, with nothing being in its rightful place, even the books on the bookshelf having been placed there in a hap-hazard fashion. But what is key are the facial expressions worn by David and Dora. David looks positively angry as he attempts to carve the mutton, his frown indicates he is completely out of patience with the state of his marital home. Dora meanwhile, appears to be very aware of her unsuccessful home-making, and with her eyes being cast downwards, it seems that she cannot bring herself to look at her dissatisfied husband.

So why does Dickens present us with Dora, the unsuccessful house-wife, desperate to be acknowledge as liminal? It is my opinion that Dora is to be understood as a warning to all about the expectations of middle-class women in a patriarchal society. If society treats women like children, they will remain as children. When discussing the nineteenth century in her book Precocious Children and Childish Adults (2012), Claudia Nelson states that “Victorian society was ordered in such a way as to keep its females perpetual children, sexually innocent, financially dependent, adorably helpless” (p.72). Dora is all the things that Nelson lists, and what Dickens is doing through Dora is exposing to the reader how damaging such a society can be. Through her liminality, Dickens reveals the painful position women find themselves in when they are expected to make the sudden transition from child to wife.

The CLiC web app has revolutionised the way I am able to analyse Dickens’s novels. I have only discussed a basic function of the CLiC web app, but my aim was to show how even the basic functions have allowed me to be more specific with my analysis of the text. Phrases such as “Dickens repeatedly uses…” have been replaced with a reference to the exact number of times a word or phrase appears and where it is most prevalent. As a result, I am confident that when I claim a particular phrase is important, I have the tools necessary to fully support my claim.

Bibliography

- Bilston, S., 2004. The Awkward Age in Women’s Popular Fiction, 1850-1900: Girls and the Transition into Womanhood. Oxford: Oxford University Press

- Browne, H. K., 1850. Our Housekeeping. [image online, scanned by Allingham, P. V.] Retrieved from the Victorian Web.

- Dickens, C., 1849-50 [2004]. David Copperfield. London: Penguin Group.

- Dickens, C.,1837-39 [1994]. Oliver Twist. London: Penguin Group.

- Dickens, C., 1864-65 [1998]. Our Mutual Friend. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Nelson, C., 2012. Precocious Children and Childish Adults: Age Inversion in Victorian Literature. Baltimore: John Hopkins University Press.

- Steadman, J. 1963. Child-Wives of Dickens. The Dickensian. 59, pp.112-119. London: The Dickens Fellowship.

Please cite this blog post as follows: Phelps, S. (2018, November 16). Liminality in David Copperfield [Blog post]. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2018/11/16/liminality-in-david-copperfield/.

Join the discussion

2 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?Comments