In this guest post, Miriam Helmers (University College London) draws on how different digital tools and sources to examine the relationship between Dickens’s journalism and his fiction. She reports very interesting insights into the writer’s use of “a fantastic kind of descriptive language”.

Charles Dickens was a reporter before he was a writer of fiction. This would be a truism – if it were true. Strictly speaking, yes, he worked as a parliamentary reporter from 1831-1834 and as a reporter for the Morning and Evening Chronicles from 1834-1836 before launching his career as a novelist. And yes, the detailed descriptions in his fictional work showcase his journalistic training. However, Dickens goes beyond the details in his fiction, and even in his early reporting, he already points to realms of unrealism. As one might expect from the genre, his early journalism does not contain many instances of figurative language; but when Dickens the detailed reporter uncharacteristically states that he cannot describe something, it may be that Dickens the imaginative writer feels that only a fantastic kind of descriptive language would be adequate – and yet would be inappropriate for him to indulge. He finds the outlet for that kind of detail in his fiction.

While I wished that I could have used the CLiC concordance tool (Mahlberg et al. 2016) to sift through barely-legible scanned versions of the newspapers from this period (see Figure 1), I was later able to use CLiC to find several examples from Dickens’s fiction that have confirmed some parts of my hypothesis.

My starting point meanwhile was the British Newspaper Archive (BNA). The BNA is a fantastic resource, containing millions of pages of newspapers dating from 1700. With a subscription, you can view as many articles as you need – although in the British Library Reading Rooms, you have unlimited access to the BNA for free! Certainly one of the perks of living in London. To look for specific articles, you simply enter keywords, or the date, or the newspaper in the advanced search and then continue limiting the search with added filters. This requires a bit of patience.

[Editorial comment: If you don’t have a subscription to the BNA, your institution might have access to other resources. For a recent and very informative overview, see the The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata (Beals & Bell, 2020), an open-access guide to digitised newspapers around the world.]

I examined the scanned versions of the papers to which Dickens contributed as a reporter from 1834-1836, carefully reading each report or review that has been attributed to Dickens (documented in Slater 1996) for examples of figurative language. A “control F” option would have been helpful sometimes, but it did not work so well with the scans or the transcripts provided, which are quite garbled. It was thus a fairly intensive “manual” search that took several hours.

“Impossible to describe”

One clue that I found as I made my way through those scanned newspapers in the BNA are two instances of Dickens stating that something is “impossible to describe” when it seems that the scene in front of him surpasses even his capacity for capturing minute details:

“To describe the bustle and animation and beauty of the city would be impossible.”

(Dickens 17 September 1834, “Report from Edinburgh on Preparations for the Grey Festival,” Morning Chronicle; cited in Slater 1996)

“[T]he imperfect state in which we saw them last night, renders it impossible even to describe one half of the numerous interesting objects which force themselves, in rapid succession, on the spectator’s attention.”

(Dickens 9 July 1835, “The Colosseum,” Morning Chronicle)

But why would he hesitate in those cases to give us all the details when he does not hesitate in other places to show off his powers of observation?

“At this period of the business there came on a tremendous shower of rain, which made the multitude fly in all directions, and which made its way through the hustings, and the temporary shelter provided for the reporters. So heavy a storm was not calculated on, nor guarded against by tarpauling [sic]; and the rain came through the hustings in water-spouts in all directions, leaving no sort of shelter for anyone. The storm continued with inveterate force for half an hour, by which time those on and under the hustings were completely drenched. (…) As to taking notes of the speeches, that was almost wholly out of the question, for as fast as any attempts were made to take notes the torrents were nearly sure to ‘swamp’ them. (…) It rained incessantly (…) and the steam rose in clouds from the saturated clothes of the dense mass in front of the hustings.”

(Dickens 2 May 1835, “Election Report from Exeter,” Morning Chronicle)

This particular report was likely written under great pressure since he wrote it while traveling by express for the piece to be printed the next morning. The pressure certainly did not stop him from dwelling on that glorious description of the downpour. (In the paper clipping in Figure 1, we can also see, with difficulty, examples of that kind of detail.)

“Some new language”

One possible explanation for why Dickens held himself back in those previous examples is that when he says something is “impossible to describe” he means that it is impossible to describe in ordinary terms. As we read in The Old Curiosity Shop (1840):

“To describe the changes that passed over Quilp’s face (…) would require some new language: such, for power of expression, as was never written, read, or spoken” (ch. 67).

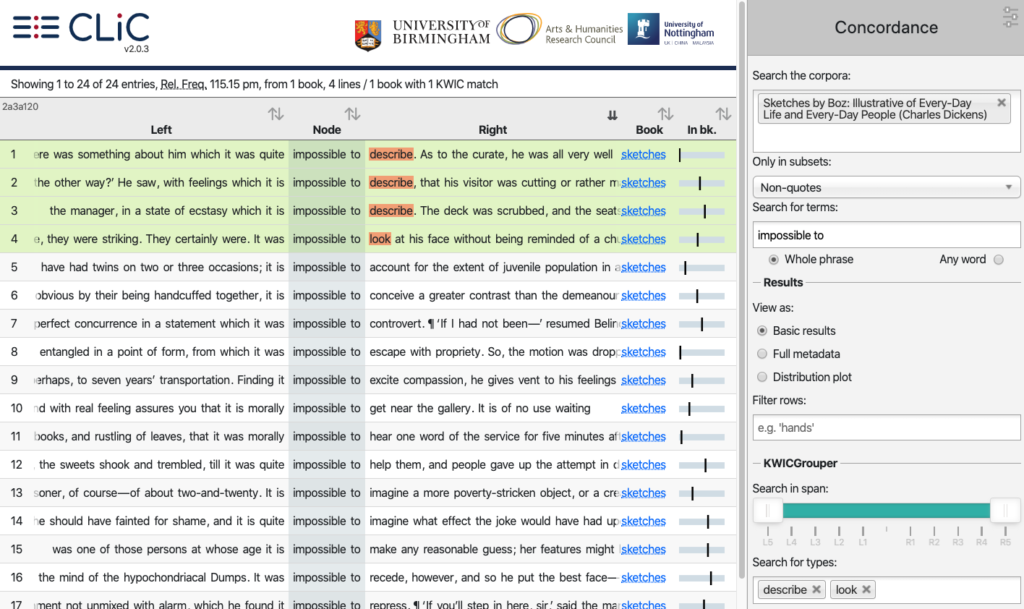

That “new language” includes the imaginative one of figurative comparison that hardly has a place in realistic reporting. Dickens’s early fiction (1833-1836), collected in Sketches by Boz (included in the CLiC ArTs – Additional Requested Texts corpus), was already an outlet for this kind of creativity. Using CLiC, we can isolate some examples of Dicken’s hyperbolic “impossibility” from the Sketches (see Figure 2). Lines 2 and 4 are excerpted below.

“[Mr. Minns] saw, with feelings which it is impossible to describe, that his visitor was cutting or rather maiming the ham, in utter violation of all established rules.”

(First published in the Monthly Magazine Dec 1833 as “A Dinner at Poplar Walk”; later “Mr. Minns and his Cousin” in Sketches – Line 2 in Figure 2)

“It was impossible to look at [Mr. Calton’s] face without being reminded of a chubby street-door knocker, half-lion half-monkey; and the comparison might be extended to his whole character and conversation.”

(First published in the Monthly Magazine, May 1834; later “The Boarding House” in Sketches – Line 4 in Figure 2)

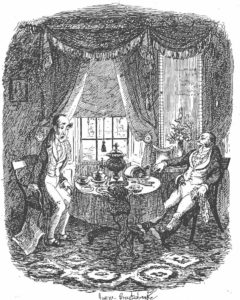

In both cases, Dickens makes the impossible possible with a flight of figurative fancy: it is impossible to describe Mr. Minns’s feelings, except that if his cousin is maiming rather than simply cutting the ham, as if the ham were still living, it is possible to imagine the horror-stricken mind of Minns (see Figure 3). And if it is impossible to see Mr. Calton without thinking of a door-knocker, well, Dickens is the one who has now made it possible for us to see that likeness.

Everything “CLiCs“

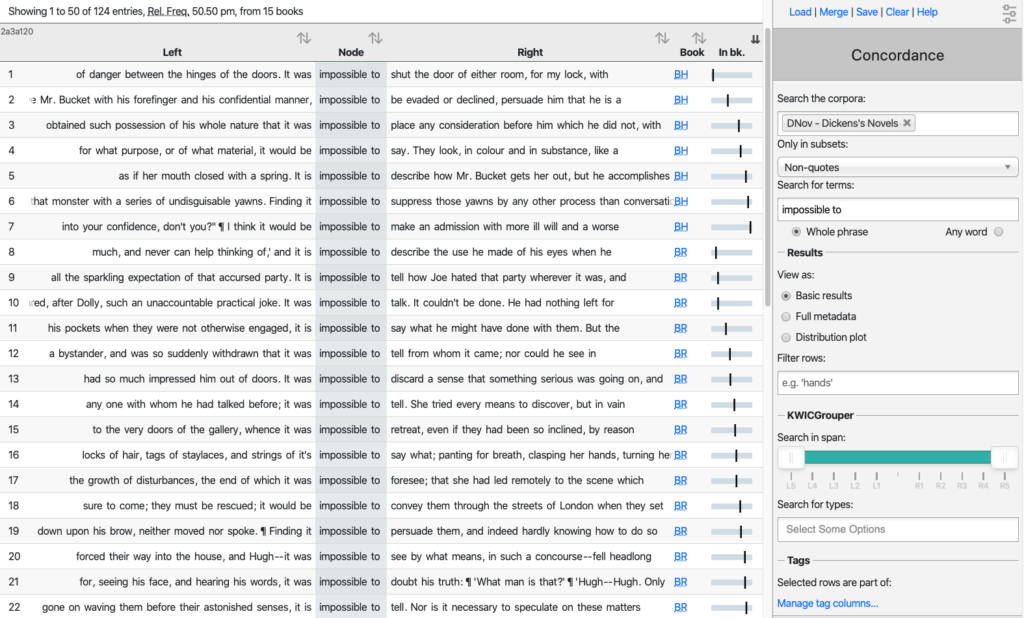

Taking a look at his later fiction, the CLiC concordance tool reveals 365 examples of Dickens’s use of the word impossible in his novels. When narrowed to only narrative text (excluding dialogue, so searching in the “non-quote” subset), and clusters of impossible to, the search reveals many examples of situations, people, and objects that are “impossible” to describe in some way (see Figure 4).

With many of these, Dickens settles for defeat (even he can find no words); but with many others, Dickens finds that “new language” to describe what would otherwise be impossible to describe, as in this passage from Bleak House (1853) where we see Jo the crossing-sweeper boy:

“He shades his face with his ragged elbow as he passes on the other side of the way, and goes shrinking and creeping on with his anxious hand before him and his shapeless clothes hanging in shreds. Clothes made for what purpose, or of what material, it would be impossible to say. They look, in colour and in substance, like a bundle of rank leaves of swampy growth that rotted long ago.”

(Dickens 1853, Bleak House, ch. 46)

The comparison is not realistic, but that is (surprisingly) how we are perfectly able to imagine the state of the poor boy’s clothes. From the same novel, we see Mr. Bucket escorting Hortense, the French maid, into custody:

“It is impossible to describe how Mr. Bucket gets her out, but he accomplishes that feat in a manner so peculiar to himself, enfolding and pervading her like a cloud, and hovering away with her as if he were a homely Jupiter and she the object of his affections.”

(Dickens 1853, Bleak House, ch. 54)

The figurative comparison can be a homely Jupiter, as in Bucket’s case, or simply homely, as in this example from Dombey and Son (1848):

“Besides these cares, the Captain had to keep his eye on a diminutive frying-pan, in which some sausages were hissing and bubbling in a most musical manner; and there was never such a radiant cook as the Captain looked, in the height and heat of these functions: it being impossible to say whether his face or his glazed hat shone the brighter.”

(Dickens 1948, Dombey and Son, ch. 49)

With that simple imagined glance from Captain Cuttle’s hat to his face, we can quickly sense what his perspiring, smiling face must look like. A final example from Dickens’s final novel, The Mystery of Edwin Drood (1870), shows how his figurative imagination plays with the impossibility of describing something in any other way.

“By what means the news that there had been a quarrel between the two young men overnight, involving even some kind of onslaught by Mr. Neville upon Edwin Drood, got into Miss Twinkleton’s establishment before breakfast, it is impossible to say. Whether it was brought in by the birds of the air, or came blowing in with the very air itself, when the casement windows were set open; whether the baker brought it kneaded into the bread, or the milkman delivered it as part of the adulteration of his milk; or the housemaids, beating the dust out of their mats against the gateposts, received it in exchange deposited on the mats by the town atmosphere; certain it is that the news permeated every gable of the old building before Miss Twinkleton was down.”

(Dickens 1870, The Mystery of Edwin Drood, ch. 9)

The news of the quarrel is objectified as if it were some kind of dust brought in at the window, some kind of yeast kneaded into the bread, etc. The phrase impossible to say acts as a springboard to a fantastic explanation (in both senses) of how it is possible to say.

Conclusion

While on the one hand, the Digital Humanities have a lot of work to do in properly scanning old newspapers (see Figure 1, again!), on the other hand, tools like CLiC point to how DH is making our work ever easier. Another DH project that will be helpful when documenting examples of Dickens’s style, for example, is the Dickens Journals Online website. This valuable resource contains scanned pages of the contributions (many his own) to the periodical journals Household Words and All the Year Round that Dickens edited, or rather carefully curated, from 1850 until his death in 1870. Dickens’s interest in journalism (essay-writing, opinion-pieces, etc.) clearly continued into his later career; but the anonymous reporting phase had long since been superseded by another that allowed him to explore objects he found “impossible to describe.”

The results of the CLiC searches in Dickens’s fiction were thus a confirmation of my hours of manual research into Dickens’s early reporting and helped me pinpoint an important aspect of Dickens’s style: his ability to make the impossible possible through imaginative language.

Suggested citation: Helmers, M. (2020, March). Dickens makes the impossible possible: Charles Dickens, Reporter? [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2020/03/17/dickens-makes-the-impossible-possible-charles-dickens-reporter/

References:

- Beals, M., & Bell, E. (2020, January 28). The Atlas of Digitised Newspapers and Metadata: Reports from Oceanic Exchanges. https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.11560059.v1

- Dickens, C. (1835, 8 July). “Colosseum.” British Library Board: British Newspaper Archive, Morning Chronicle.

- Dickens, C. (1835, 12 January). “Essex. – Nomination.” British Library Board: British Newspaper Archive, Morning Chronicle.

- Dickens, C. (1835, 2 May).“Express from Exeter … South Devon Election.” British Library Board: British Newspaper Archive, Morning Chronicle.

- Mahlberg, M., Stockwell, P., de Joode, J., Smith, C., & O’Donnell, M. B. (2016). CLiC Dickens: Novel uses of concordances for the integration of corpus stylistics and cognitive poetics. Corpora, 11(3), 433–463. https://doi.org/10.3366/cor.2016.0102

- Slater, M. (1994). The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens’ Journalism, Vol. 1: Sketches by Boz and other Early Papers 1833-39. London: J. M. Dent.

- Slater, M. (1996). The Dent Uniform Edition of Dickens’ Journalism, Vol. 2: “The Amusements of the People” and Other Papers: Reports, Essays and Reviews 1834-51. London: J. M. Dent.

Join the discussion

1 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?Comments