Ventriloquy is the art of speaking in such a way that one’s voice appears to come from another source. When it comes to writing believable dialogue, writers of historical fiction are a bit like ventriloquists.

How can modern writers give the impression that their characters are conversing in the past? What research methods can we use to pull off this rhetorical feat? In this research activity we’ll be using the CLiC Web App to explore how to craft dialogue that authentically reflects a given historical period.

It is important to reflect on your character’s tone and vocabulary, as well as what might have been popular or contentious topics of conversation in your chosen era.

Tip: Keep in mind your character’s gender, age, and social class when considering what would have been deemed “appropriate” conversation etiquette. This doesn’t mean that your characters must act in a certain way, but its useful to be aware of deviations from literary and cultural norms of the time.

The first step to writing believable dialogue is to effectively eavesdrop on historical conversations. The following activity demonstrates how you can use CLiC to immerse yourself in the language of the time period you want to emulate.

Research Activity: Historical Ventriloquism

This activity can also be downloaded as a handout here.

The thing about speech is that it’s full of ‘clusters‘, i.e. words that appear together as repeated sequences. CLiC’s ‘cluster‘ feature can help you zoom in on this phenomenon.

INSTRUCTIONS:

1. Go to clic.bham.ac.uk and click ‘clusters’. Clusters are also called ‘n-grams’, where ‘n’ stands for the number of words are repeatedly found together in a sequence.

2. Select several texts from the drop-down menu under ‘search the corpora’. See our earlier building your corpora handout for further guidance.

3. Under the subsets option, select ‘quotes’.

4. Under ‘n-gram’ select an option. CLiC supports clusters of up to 7 words (I am very much obliged to you), but you will get more results for clusters that contain fewer words.

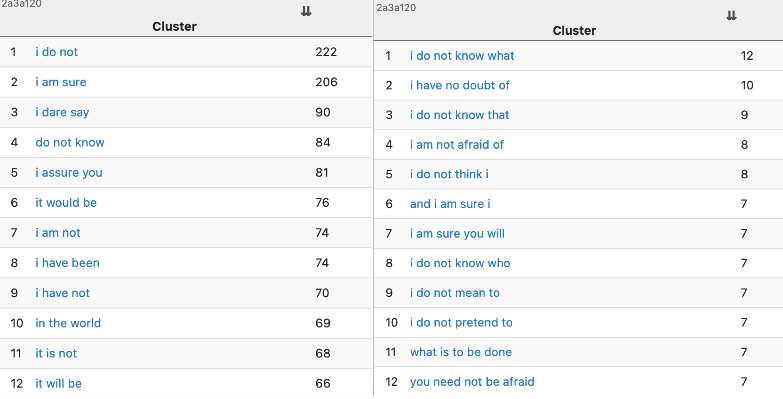

5. Look through your results, sorted by frequency. Below is a list, sorted by frequency, of the top 3-gram and 5-gram clusters that occur across Jane Austen’s Pride and Prejudice, Persuasion and Emma. Take note of any phrases you feel might sit comfortably in the mouths of one of your own characters. Aspiring Regency writers among you might consider conversational clusters like to be sure, much obliged, and I dare say.

6. You can click through to run a concordance for a specific cluster. Here, you can gather further information about the use of these phrases. Note down any context you feel is important such as the gender or class of the speaker, the circumstances of the conversation, or the relationship between the parties conversing. If you require further context, you can individually click each concordance line to be taken to the text. If you detect a pattern, you can filter your results further using the filter rows option or the KWIC Grouper.

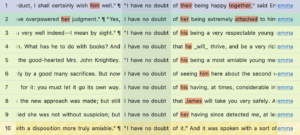

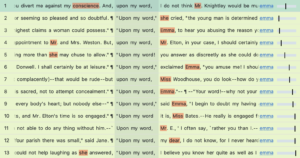

The cluster, I have no doubt, for example, occurs sixteen times in Jane Austen’s Emma. In a number of cases, it is used by a woman in either direct or oblique reference to the perceived marriageability of a specific man.

Likewise, the cluster upon my word is nearly always used by women in exclamation, often in reference to the boldness or perceived impudence of Emma herself.

The frequency of clusters containing modal verbs (must, can, would, should, may, will, shall etc) is also interesting to look at!

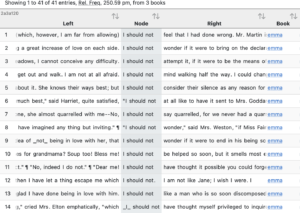

Men and women were acutely aware of what they ought to do, even if these actions were at odds with their inner desires. Women, in particular, existed in a constant state of obligation towards their families, friends, and even acquaintances. In an era when the concept of dating was yet to fully emerge, many were often compelled to draw large inferences from momentary meetings with potential suitors. The sense of doubt that accompanied this period of courtship is palpable. See, for example, the cluster I should not.

7. Alternatively, if you are interested in the dialogue that surrounds a specific topic, then you can run a concordance search for various words related to this topic directly, selecting the subset ‘only quotes’ and marking the ‘any word’ option. See, for example, this concordance search on marriage.

8. What catches your eye in terms of vocabulary and sentence structure? Pay close attention not only to what characters say but to how they express themselves: the slang or idioms they use and the syntax and of their speech. How do their thought patterns differ from ours? You can note down your findings in our handout in the first box marked ‘research’.

9. In the second box marked ‘application’ you can consider how you might apply what you have discovered to a specific scene or exchange between characters in your own writing. This might be nothing more than a slight shift in syntax, or the inclusion of a colloquial phrase.

Tip: take care not to overwhelm your readers with unfamiliar jargon — you can simplify certain debates, paraphrase more complex terms, or provide contextual hints in your dialogue, if necessary. At the same time, ‘info-dumping’ can feel forced.. Gradually weave information into your story in a way that feels natural. Try to think about how you can imply or infer contextual information instead of providing extensive exposition.

If we got you interested in research on fictional historical speech, maybe have a look at this article, which you can download for free as an open access paper – Mahlberg, M., Wiegand, V., Stockwell, P., Hennessey, A. (2019). Speech bundles in the 19th-century English Novel, Language and Literature, 28(4) 326–353. https://doi.org/10.1177/0963947019886754

Bonus Writing Activity: From Card Games to Carriage Rides

Writers frequently used specific activities to structure their dialogue. Jane Austen, for example, made use of dances, picnics, card games and carriage rides. Write a scene built around an activity that is particularly evocative of your chosen period. Use the prescribed etiquette, rules or customs of this activity as a guide to inform the feel or direction of your dialogue.

If you found either of these activities useful, why not post some of your findings under the hashtag #CLiCCreative, or by tagging us @CLiC_fiction on Twitter?

You can download this research activity here. Previous #CLiCCreative posts by Dr Rosalind White are available here.

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?