Whether by rail, on foot, via stagecoach, in a carriage, or aboard a ship, journeys play a pivotal role in novels of the long-nineteenth century. What can we learn about what it was like to travel in another time? In this research activity we’ll be using the CLiC Web App to learn about modes of transport and the changing culture of travel in this era. Previous #CLiCCreative posts by Dr Rosalind White are available here. This post is also available as a handout.

Historical Overview

Historical Overview

LATE GEORGIAN

Walking, horseback riding, stagecoaches, and canal boats were the primary modes of transport. Horse-back and private carriage riding (via gig, phaeton or curricle) were largely reserved for the rich. Though this period is often referred to as the “Golden Age” of British canals, stagecoaches were more commonly used for long-distance travel.

VICTORIAN ERA

More affordable, smaller omnibuses travelling fixed routes gradually replaced traditional stagecoaches. Meanwhile, railway mania swept the nation, spiriting away passengers of all classes from the cities to remote corners of the coastline. The turn of the nineteenth century coincided with the popularisation of the bicycle and an increase in use of steam ships.

Tip: Remember that the mode of transport your character is using might be a relatively new phenomenon, so they ought to act accordingly. Many in the Victorian era, for example, were concerned that hurtling along in a railway carriage at high speed could shatter nerves, trigger insanity, or otherwise damage one’s body. Queen Victoria journeying from Slough to London famously demanded that the driver slow down to less than 30 miles per hour.

Research Activity: Journey to the Past

This activity can also be downloaded as a handout.

INSTRUCTIONS

Taking into account the period in which your novel takes place, list as many terms relating to travel and/or modes of transport as you can. Make sure to include synonyms.

You can use this list as guidance.

boat, canal, carriage, cart, coach, curricle, distance, gig, journey, miles, outing, passenger, phaeton, railway, ride, river, road, ship, stagecoach, station, steam, tour, train, tram, travel, trek, trip, vehicle, voyage, wagon, walk.

Select a number of texts according to the period in which your novel takes place. (This is called building your corpora)

Go to clic.bham.ac.uk, click ‘concordance’, and select these texts from the drop-down menu under ‘search the corpora’. You can automatically select a sample of texts in a given era by using the following links:

-

- works set in the Georgian era (1714-1837)

- works set in the Regency era (1811-1820)

- works set in the early nineteenth century (1800-1837)

- works set in the mid-Victorian era (1837-1880)

- works set in the fin de siècle (1880-1900)

Select ‘all text’ under the subsets option.

Type one of the terms you noted earlier under ‘search for terms’ and hit enter.

Remember, an asterisk can be used as a wildcard – so travel* would also find travelling or travelled. If you’d like you can type in multiple terms at once, you can do so by selecting the ‘any word’ option.

What can you learn from your concordance results about what it would have been like to travel in your chosen era?

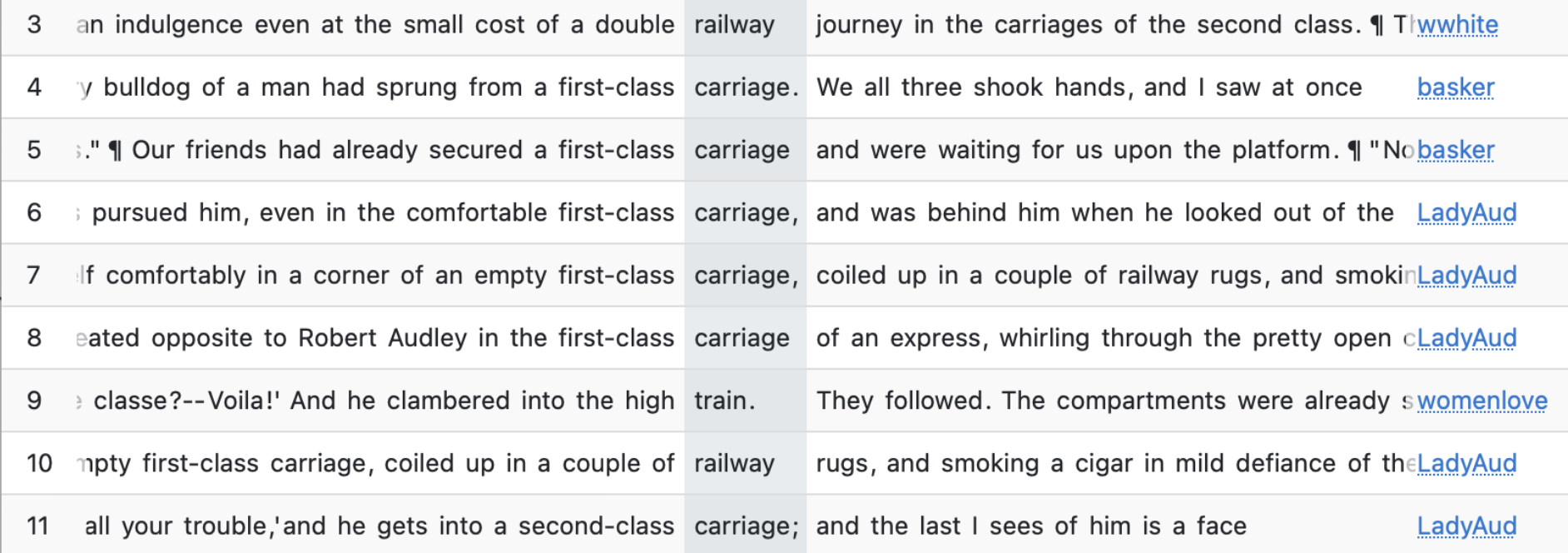

Does class play into your character’s travel circumstances? Are passengers seated according to rank or are social barriers broken down between individuals who may not otherwise have interacted? In the concordance below, we already see a difference between first and second class travel!

What is the etiquette associated with this mode of travel? And how does this impact upon the kind of interactions characters have?

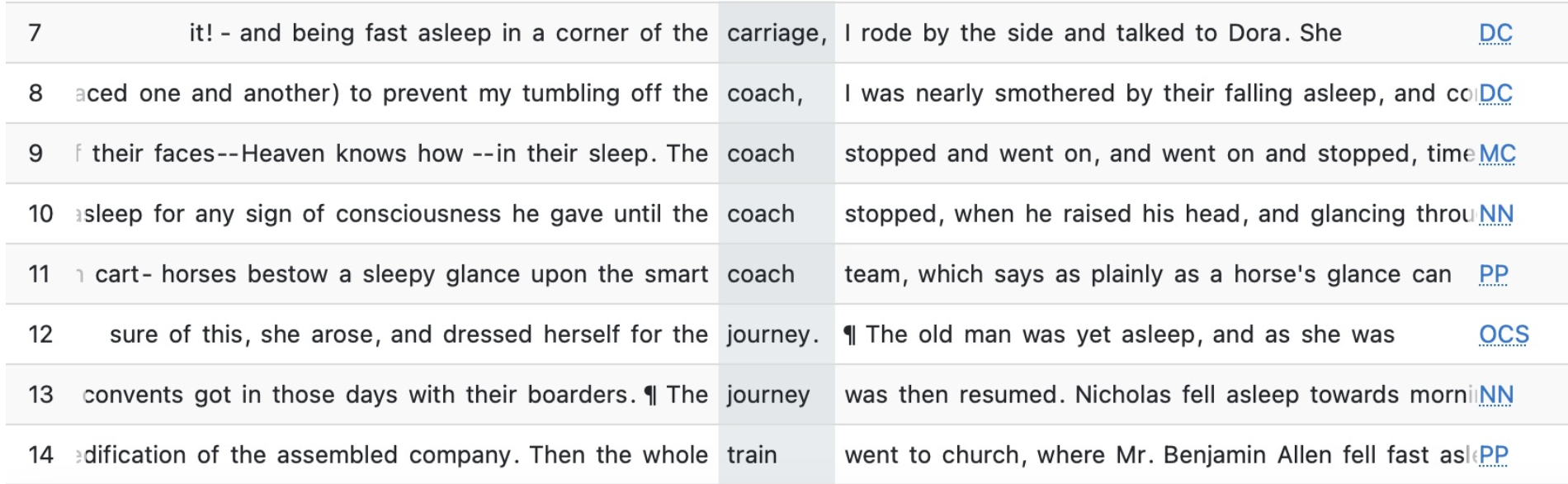

Socially acceptable sleeping, for example, might facilitate a private conversation between passengers who remain awake. But it seems falling asleep can also make the journey uncomfortable for others, as you can see in line 8 below where David Copperfield is wedged in between two gentlemen when he travels to London.

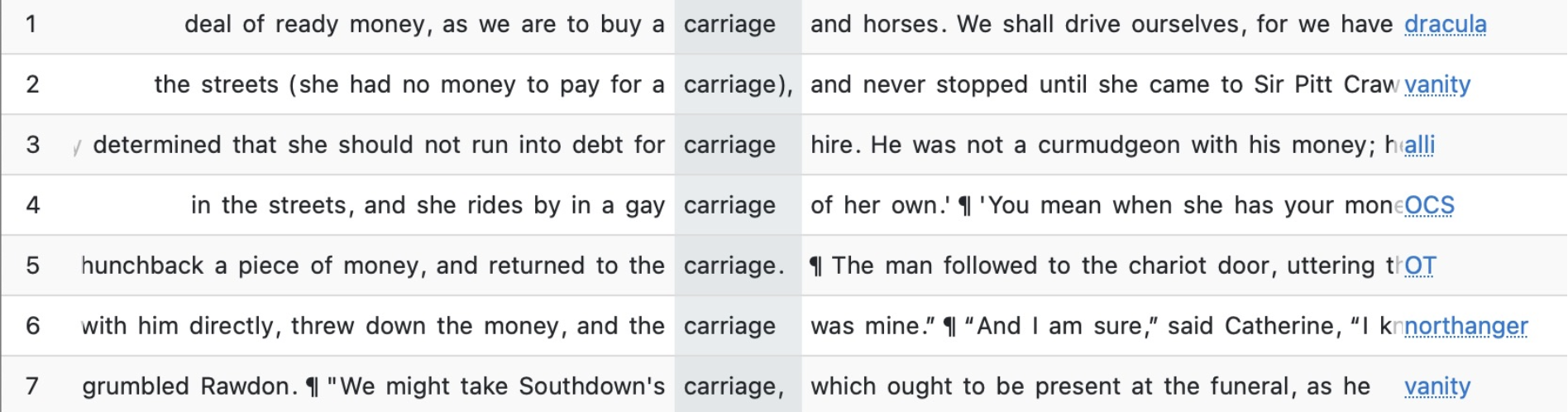

What was the cost associated with travelling?

Would your characters (like Van Helsing and his team in Bram Stoker’s Dracula) ‘have a good deal of ready money’ (see line 1) and thus have no problem procuring a carriage at a moment’s notice? Or would even hiring transportation put them at risk of debt?

Pay close attention to the words that sit on either side of your chosen term (in corpus linguistics, these are called ‘collocates’).

Keep in mind the book each concordance line originates from (this is listed on the right- hand side).

If you detect a pattern, you can filter your results further using the ‘filter rows‘ option or the KWIC Grouper.

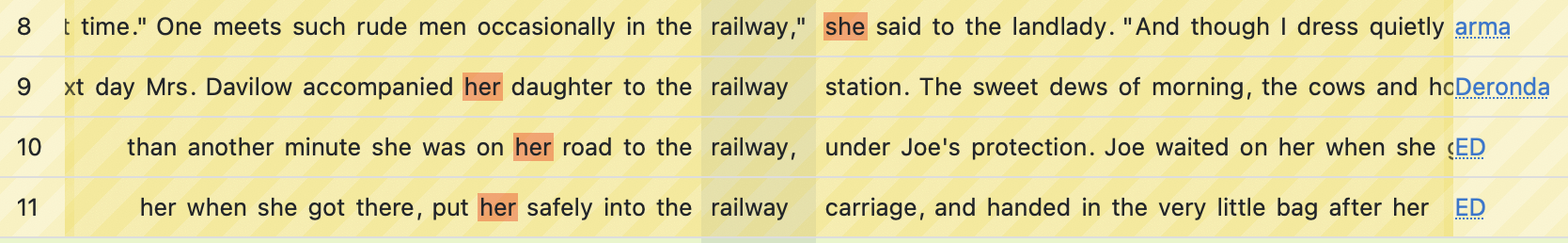

You can run a concordance search for a mode of transportation and then filter your results using female pronouns and possessives (she, her, hers) if you would like to examine the cultural restrictions placed on the mobility of girls and women.

The railway, for example, presented nineteenth- century women with new opportunities and new dangers in equal measure.

For the first time, they could travel on their

own over long distances without the need for a chaperone. But, (like their twenty-first century counterparts) they often felt unsafe or vulnerable on public transport.

Crowded trains meant that they could easily find themselves sharing a carriage with a group of male strangers, who could be rowdy or even predatory. What’s more, a woman who was being harassed could not quickly get away, as carriages were only accessible from a door at either end.

To counter these concerns, ladies-only carriages were

introduced in the latter half of the century. These carriages (which numbered over 1,000 by 1888) were usually located at the front or back of the train. Some women also took the precaution of dressing in a more conservative manner, adopting high necklines or long skirts.

See lines 10 and 11 of the concordance search below, where Miss Rosa Bud (from Charles Dickens’ Edwin Drood) is escorted to the train station under male protection; or line 8 where Lydia Gwilt (the shrewd anti-heroine of Wilkie Collins’ Armadale), remarks on the ‘rude men’ she has met while travelling alone on the railway. As she explains to her landlady, though she dresses ‘quietly’ her red ‘hair is so very remarkable’ – so to deter unwanted male attention she is accustomed to wearing a ‘thick veil’.

What can you ascertain from your results in terms of what it would have been like to travel — as a woman — in you chosen time?

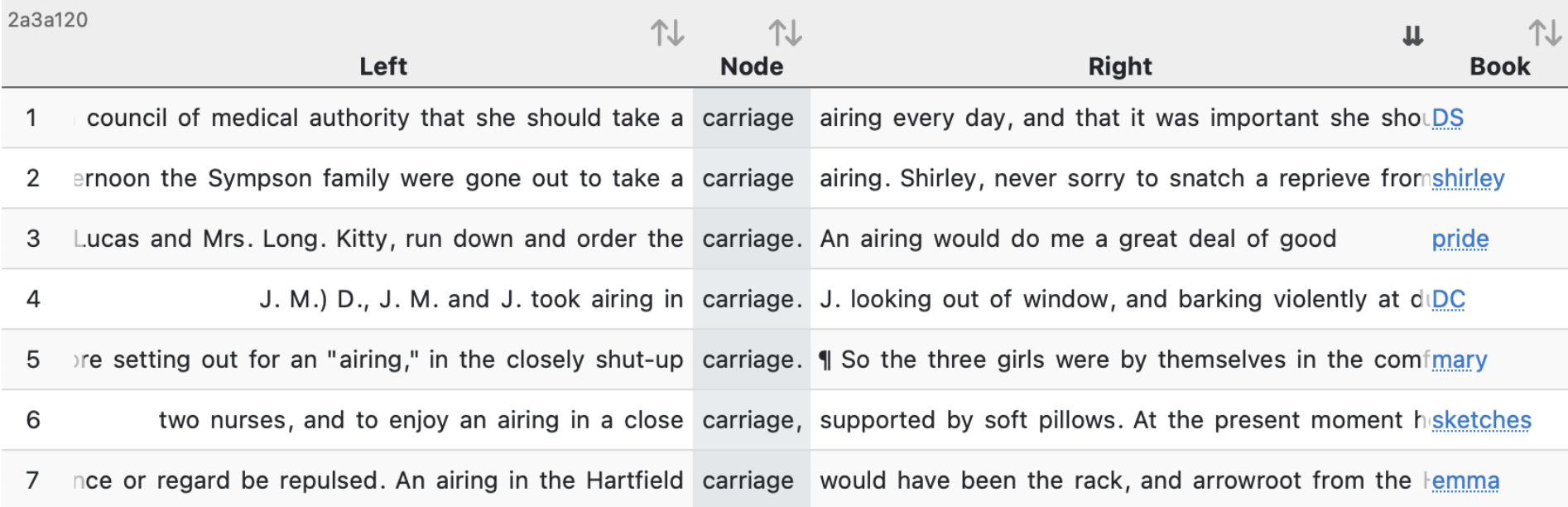

Look for patterns that offer contextual insight. You might notice, for example, that the word airing collocates with the word carriage.

Carriage airings were a popular and socially acceptable way for women to see and be seen by society outside of one’s family. Though health was often cited as the reasoning behind such a journey, women also made an event of the enterprise itself, inviting friends, dressing up, and driving to a picturesque location.

Keep an eye out in your research for writing strategies crafted to bring specific modes of transport to life.

See, for example, Dickens’ descriptive railway panorama in Dombey and Son that utilises repetition, rhythmic punctuation, and cyclical syntax to evoke what it would have felt like to journey aboard a train for the first time.

“Away, with a shriek, and a roar, and a rattle, through the fields, through the woods, through the corn, through the hay, through the chalk, through the mould, through the clay, through the rock [. . .] Through the hollow, on the height, by the heath, by the orchard, by the park, by the garden, over the canal, across the river, where the sheep are feeding, where the mill is going, where the barge is floating, where the dead are lying, where the factory is smoking, where the stream is running, where the village clusters, where the great cathedral rises, where the bleak moor lies, and the wild breeze smooths or ruffles it at its inconstant will.” – Charles Dickens, Dombey and Son, Chapter 20.

You can note down what you have discovered in the downloadable handout provided and post your findings under #CLiCCreative, or by tagging us @CLiC_fiction on Twitter.

Bonus Writing Activity

Write a scene in which one of your characters is taken outside of their comfort zone while in transit. What is it about this journey that enables them to meaningfully interacts with the world around them? Along the way what do they learn about themselves, or another character? How does the journey itself inform this internal growth? Weave in what you have learnt in the previous research activity.

You can write your answers in the downloadable handout provided.

Why not post your findings under #CLiCCreative, or by tagging us @CLiC_fiction on Twitter?

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?