In this post, Chris Jones (University of Liverpool) shows how the CLiC quotes subsets can be explored to aid English language teaching. He provides a sample activity from his recent open access article in the Journal of Second Language Teaching & Research, co-authored with David Oakey.

Nineteenth century fiction may seem an unlikely place to find good models of English conversations for use in the 21st century. However, recent research I have co-authored shows that there are a number of similarities between the dialogues we find in the corpora of the CLiC web app (Mahlberg et al., 2016) and the kinds of conversations English as a second language learners may need to have and understand in the present day. More details on these findings can be found in the open access article (Jones & Oakey, 2019). This short post will briefly explore why and how a language teacher could use the corpus to model and explore the language of conversation.

Why use fictional dialogues?

There are a number of reasons why teachers may wish to use dialogues from fiction but here I outline two main ones. Firstly, such materials have the potential to be both interesting and motivating when viewed from a pedagogical perspective (e.g. McRae, 1991; Carter & McRae, 1996). Many learners read literature in their first and second language (either in the original or a simplified form) and we can therefore assume that many will have an interest in the dialogues contained within novels, short stories or plays. A parallel argument is that such dialogues can form part of a text-based approach to second language instruction (Timmis, 2018), where a teacher chooses texts (in this case dialogues) based on whether they are engaging, rather than because they contain specific language areas. Materials using such an approach have received positive feedback from teachers in a range of contexts and also match several aspects said to be key in second language acquisition such as the need for learners to receive a rich variety of input (Tomlinson, 2013). Secondly, there are few recordings of unscripted conversations available to teachers (see Carter & McCarthy, 1997, for one example) and should teachers choose to use conversation transcripts from spoken corpora, such conversations are often far removed from learners’ own interests and tend to need a lot of supporting material and guidance (see Carter, Hughes, & McCarthy 2000 for a helpful example of such material.)

How to use the CLiC web app to explore dialogues in ELT

In order to use literary dialogues, teachers can explore the CLiC web app to look for dialogues on the basis that they are likely to engage a particular group of learners, rather than because they contain certain forms. This is relatively simple to do and the basic steps are as follows:

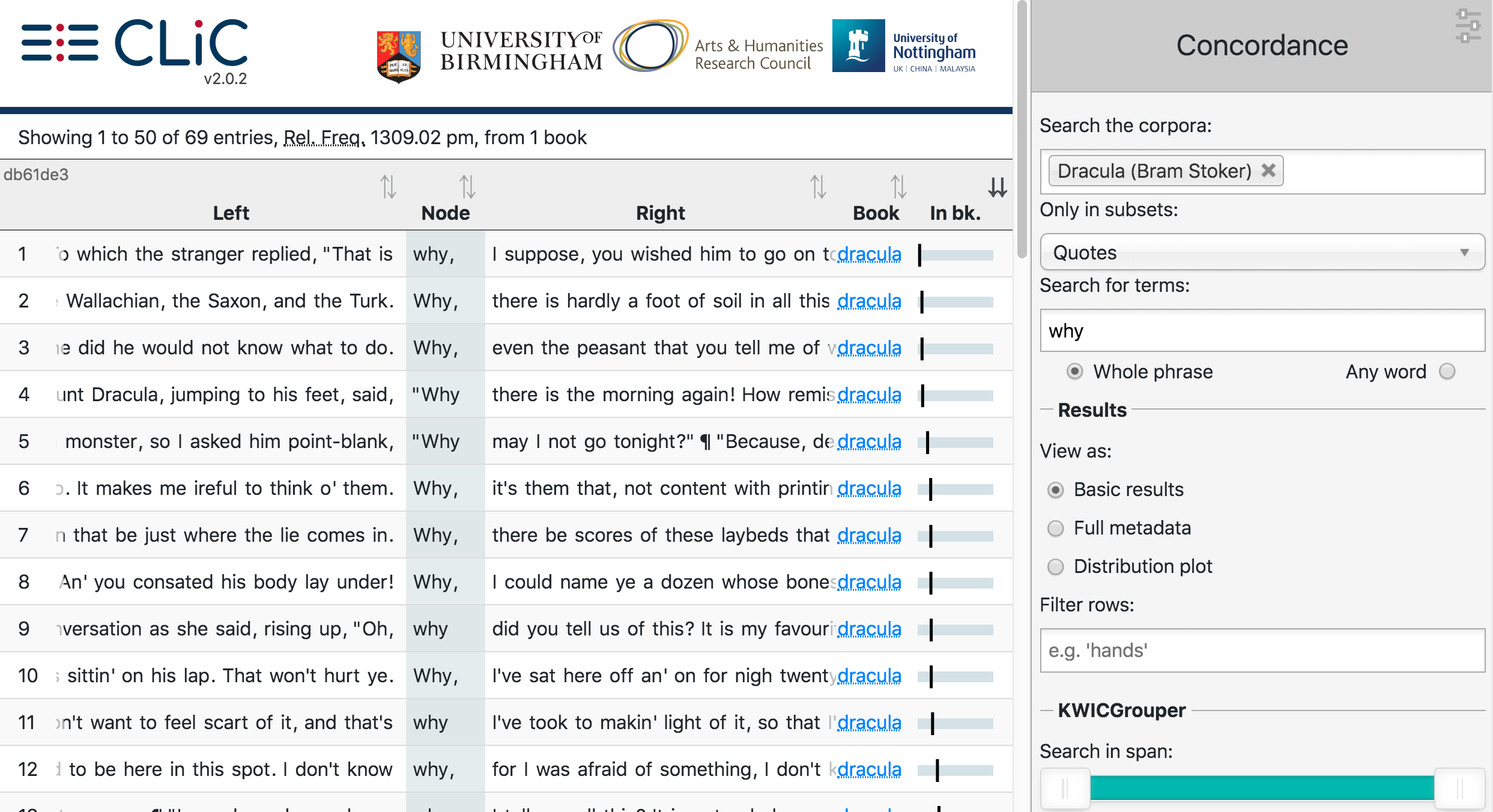

- Open CLiC and choose a text or corpus to explore. In this example, I will use Bram Stoker’s Dracula form the CLiC 19th century reference corpus.

- Select ‘quotes’ from the ‘only in subsets’ option and this will display language used only in dialogues.

- Choose a search term – this could be the name of a character of perhaps a word you felt was of potential interest. In this case I have chosen the word ‘why’.

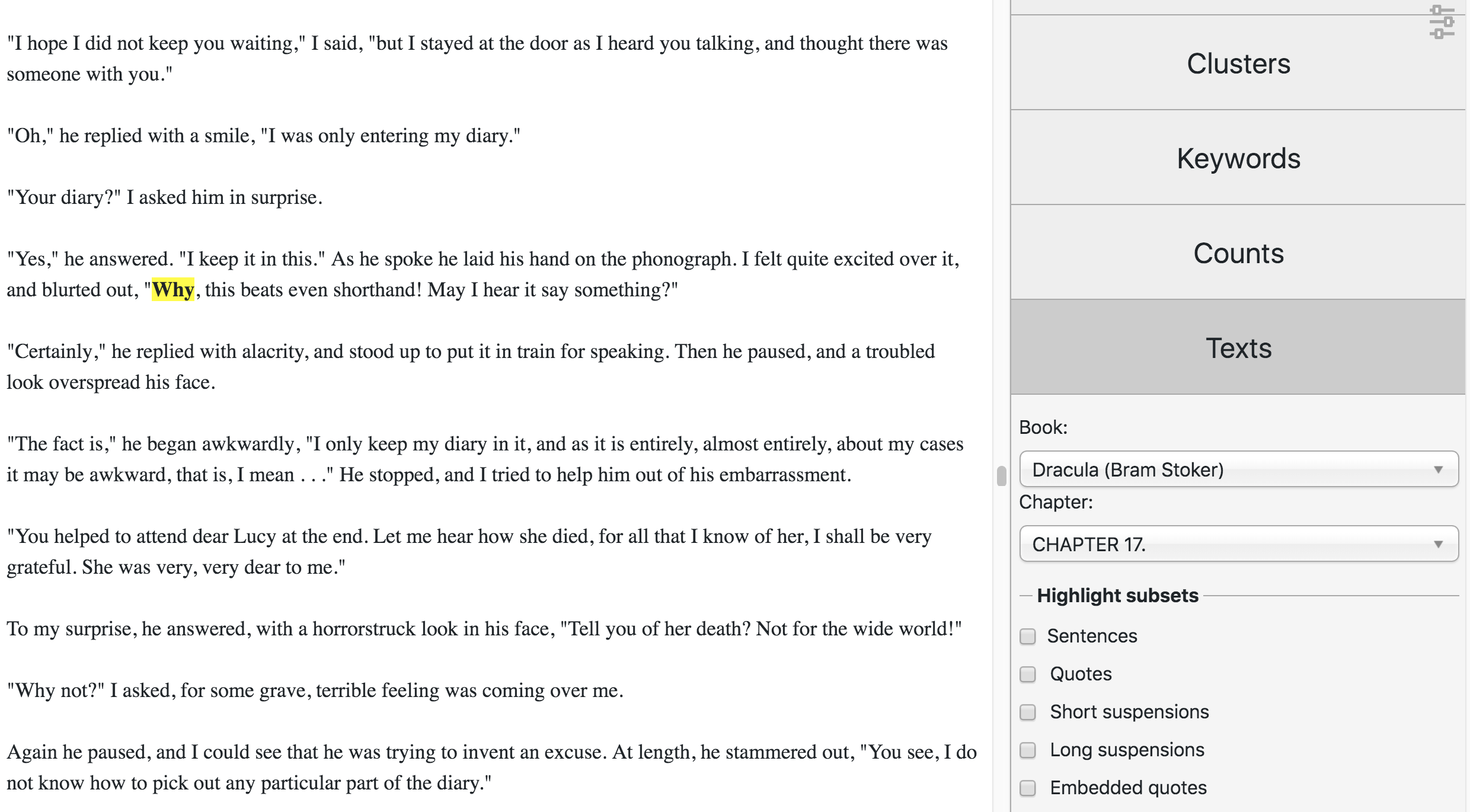

- Examine the dialogue by viewing ‘in book’ (the key word searched for will be highlighted) and decide if the conversation is potential engaging and useful to learners. They may, for example, have previously read this book or chapter and it might contain examples of common conversational language.

Steps one to four are shown in the screenshots below, Figure 1 shows steps 1-3 and Figure 2 shows step 4.

After a suitable dialogue has been found, an “Access, Activity and Awareness framework” (Jones & Carter, 2012) can be used to develop this as classroom material. The first step simply means creating an “access” point for learners and exploiting this via lead-in activities. “Activity” involves students actively participating in working with the texts. This can include typical communicative activities such as prediction or re-assembling texts. Finally, awareness” activities involve students discussing and highlighting spoken language features in the text and discussing the connection between form(s), meaning and language choice. A short sample of a simple class activity is given below to demonstrate this, using a dialogue from the 19th century CLiC web app.

A sample activity

Sample activity using a literary dialogue (from Jones & Oakey, 2019, p. 134).

From Conan Doyle, A (1902.) The Hound of the Baskervilles, Chapter 2. Extract from CLiC (2019):

‘I have in my pocket a manuscript,’ said Dr. James Mortimer.

‘I observed it as you entered the room,’ said Holmes.

‘It is an old manuscript.’

‘Early eighteenth century, unless it is a forgery.’

‘How can you say that, sir?’

‘You have presented an inch or two of it to my examination all the time that you have been talking. It would be a poor expert who could not give the date of a document within a decade or so. You may possibly have read my little monograph upon the subject. I put that at 1730.’

‘The exact date is 1742.’ Dr. Mortimer drew it from his breast- pocket. ‘This family paper was committed to my care by Sir Charles Baskerville, whose sudden and tragic death some three months ago created so much excitement in Devonshire. I may say that I was his personal friend as well as his medical attendant. He was a strong-minded man, sir, shrewd, practical, and as unimaginative as I am myself. Yet he took this document very seriously, and his mind was prepared for just such an end as did eventually overtake him.’

Access:

- Ask students how good they are remembering details when they see things.

- Play ‘Kim’s game’ in groups. Present students with a tray of objects for a few seconds and then cover it. Groups compete to remember the most objects and where they were placed.

- Ask students to recall what they know about Sherlock Holmes’ character e.g. he is clever/a good observer/he remembers things. Explain that you will be looking at a short dialogue which shows this.

Activity:

- Give students the dialogue above to read. As they read, ask them to ‘picture’ the scene i.e. the room, the people in etc. They then describe that to each other and note differences.

- Ask students some simple comprehension questions: what does Sherlock notice here? How? Why is Mortimer surprised?

What do you think is written on the document t? Why do you think this might be important for the story? What do you think will happen next?

These are obviously open questions with no set answers

Awareness:

- Underline all the examples of ‘it’ and ‘that ’in the conversation. When are they used to refer back to things already mentioned? What do they refer to? Do you use these items in the same way when you speak?

- Underline the phrases which means ‘I do not understand how you know that’ (How can you say that?). When we use this phrase how do we normally feel (surprised or annoyed). Think of a situation where you might say this to someone. Do you have a similar expression in your first language? What is another way to say this? (How do you know that?)

(You can download this activity as a PDF file [220KB]).

Literary texts as an engaging source of dialogues for learners

Such activities do not, of course, replace the need for learners to practise the conversations they need to have or from exploring present day dialogues from other media such as films and television. Literary dialogues we can explore in a corpus such as the CLiC corpora simply offer teachers and learners a potentially rich and engaging source of material and by exploring these dialogues, teachers can help to raise learners’ awareness of common features of conversational English.

References

- Carter, R., Hughes, R., & McCarthy, M. (2000). Exploring Grammar in Context. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carter, R., & McCarthy, M. (1997). Exploring Spoken English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Carter, R, & McRae, J. (Eds.) (1996). Language, Literature and the Learner: Creative Classroom Practice. Oxon: Routledge.

- CLiC.(2018). Retrieved from www.clic.bham.ac.uk

- Jones, C., & Carter, R. (2012). Literature and language awareness: Using literature to achieve CEFR outcomes. Journal of Second Language Teaching and Research, 1(1), 69 –82.

- Jones, C., & Oakey, D. (2019). Literary dialogues as models of conversation in English language teaching. Journal of Second Language Teaching and Research, 7(1), 108-135.

- Leech, G., & Short, M. (2007.) Style in Fiction: A Linguistic Introduction to English fictional Prose (2nd Edition). Harlow: Longman.

- Mahlberg, M., Stockwell, P., de Joode, J.,Smith, C., & O’Donnell, B.( 2016.) CLiC Dickens: Novel uses of concordances for the integration of corpus stylistics and cognitive poetics. Corpora, 11(3), 433–463.

- McRae, J.(1991). Literature with a Small ‘l’. London: Macmillan.

- Timmis. I. (2018). A text-based approach to grammar practice. In C. Jones (Ed.), Practice in Second Language Learning (pp 79 –108). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Tomlinson, B. (2013). Developing principled frameworks for materials development. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing Materials for Language Teaching (pp. 95-118). London: Bloomsbury.

Please cite this blog post as follows: Jones, C. (2019). Conversations in the CLiC corpora: Exploring their potential as models for dialogue in ELT [Blog post]. CLiC Fiction Blog, University of Birmingham. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2019/09/06/conversations-in-the-clic-corpora-exploring-their-potential-as-models-for-dialogue-in-elt

Join the discussion

0 people are already talking about this, why not let us know what you think?