This post by Samina Ansari, Junior Vice President of the Birmingham & Midland Institute (BMI), kicks off our new ‘BMI lockdown life’ series of guest posts. This series is a collaboration with the BMI blog, where the posts are published simultaneously. Samina highlights the historical importance of the BMI as a cultural hub and its close ties with Charles Dickens in the 1850s and 1860s. It is our hope that this series will provide a platform for existing members to engage with the BMI virtually – and that it will welcome new visitors and friends to the BMI community, who will eventually also join the physical events at Margret street when it is safe for the BMI’s Core programme to resume! The BMI lockdown life series will feature posts related to the teaching, research, and anecdotes of 19th century culture and literature. If you would like to get involved, please contact us at clic@contacts.bham.ac.uk or via Twitter (@CLiC_Fiction).

Guest editors Viola Wiegand and Michaela Mahlberg, University of Birmingham

Charles Dickens didn’t think of Birmingham in the same way as the aunt in Austen’s Emma. He thought that plenty of good could come out of Birmingham. He loved the town, as it was then, he loved the industrious and friendly people, and he wanted to help the people thrive.

In the mid-nineteenth century, a group of local philanthropists, headed by Arthur Ryland, wanted to bring the numerous and disparate places of learning that had sprung up throughout the town and its environs under one roof, and proposed the idea of The Birmingham and Midland Institute. Ryland would become the Institute’s first General Secretary; an Act of Parliament was passed saying that Birmingham Corporation could sell the Institute some land so the building could be built, and Ryland approached Dickens to perform some public readings to raise money for the building and ongoing work. Dickens’ replies to these letters, and his thoughts on Ryland, can be read in his published letters of 1853 and 1854 (see e.g. The Pilgrim Edition – the online version requires subscription; previously unpublished letters are freely available from The Charles Dickens Letters Project). While Dickens had, of course, read his stories to friends and family before, he had never read them publicly, and was a little concerned about how they would be received. But his fears were allayed, and he agreed to doing three public readings in the Town Hall to raise funds for the BMI.

His conditions were stringent. On the 28th December, 1853, he read The Cricket on the Hearth, and the seats were full price. On 29th December, he read The Chimes and the seats were half price, allowing people of more straightened means to attend. On the 30th December he rested his voice, even forgoing a meal out. On 30th December, he insisted that there were no seats at all to make more room, tickets were to be a quarter of the original price, and only working class people were to attend. He saved the best till last and read A Christmas Carol. Contemporaneous accounts say that you could have heard a pin drop, the audience was so enthralled, and the enthusiasm among his listeners was intoxicating. Thus he raised a good deal of money for the Institute.

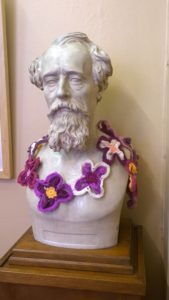

His interest in the city remained, and he became the 16th President of the Birmingham and Midland Institute. His letter of acceptance for the post is framed on my office wall.

The BMI was listed as the second most important building in ‘Birmingham Institutions’ in 1901. Sadly, we are not quite at that status any longer. The remit of the Institute is for ‘the dissemination of education to people of all classes in Birmingham and the Midlands’. It was well used and much loved for many years as a place of learning for those who had not had an extensive education before they became workers, but slowly that ebbed as schooling became compulsory. We now have a cultural programme and have been voted the most interesting room hire venue in the city. One of the events we hosted was the CLiC Dickens Day in 2017 that has led to an ongoing collaboration with the CLiC team, and now to this series of blog posts.

We are, of course, in lockdown now, but we are hoping to start a new Core programme as soon as possible, with the teaching of Arts and Crafts taking a more prominent position, as this will move us closer to our original remit.

Samina

Junior Vice President of the BMI

Head Librarian of the Original Birmingham Library at the BMI (that’s another story)

Suggested citation: Ansari, S. (2020, May). How the BMI gave Charles Dickens a new career [Blog post]. University of Birmingham: CLiC Fiction Blog. Retrieved from https://blog.bham.ac.uk/clic-dickens/2020/05/08/how-the-bmi-gave-charles-dickens-a-new-career/

Enjoyed this post? The Birmingham & Midland Institute has set up a fundraising campaign to “offset the income which would usually keep the BMI running as the social and cultural hub that it should be, and encourage you to donate to what is an important lifeline for many older people in our society.” Check out their fundraiser here.

It is certain that Samina would have had to hand a copy of Rachel Waterhouse’s book, ‘The Birmingham and Midland Institute 1854-1954’. I say ‘certain’ for Mrs Waterhouse, writing of Dickens readings, says that they ‘began a new career for Charles Dickens, for this was the first of those public readings of his own works for which he later became so renowned’. The title of Samina’s piece so clearly mirrors this earlier suggestion.

There is also a reference to The Pilgrim Edition of the Letters of Charles Dickens although the ‘see e.g.,’ might suggest that this is just one of several possible sources; whereas it is the only source, other earlier collections being superseded by it. Samina never consulted the volumes for had this been done errors in the article would have been avoided. It is said, for example, that ‘Ryland approached Dickens to perform some public readings. This was not the case.

On 6 January 1853, Dickens had been presented, at the rooms of the Society of Artists, in New Street, Birmingham, with a silver salver and a diamond ring, subscribed for by shilling contributions and afterwards entertained at a banquet given at Dee’s Royal Hotel. As he left Birmingham to return home, Dickens mentioned to Linnaeus Banks the Secretary of the Society, that he had it in mind to offer to help raise money for the proposed Institute by giving one or two readings from ‘A Christmas Carol’ during the Christmas season at the end of the year. He wrote from London the next day putting the idea to Arthur Ryland one of those who had taken a lead in promoting plans for the Institute.

There is not the subsequent flow of letters between the two men that Samina suggests. Such references as there are in the Pilgrim Letters are drawn from the minutes of various committees of the proposed BMI. Although the Pilgrim editors treat each of these mentions as though Dickens had written another letter, it may well be that the entries are no more than a repetition of what he had written in January. I

t is not until late August that we have Dickens replying to an actual letter from Arthur Ryland setting out proposals of the Institute committee. Writing from France, he makes two suggestions, one of which is accepted: that there is an evening’s break between the first and second readings.

A note of annoyance comes through in a letter to his assistant editor on Household Words, W.H. Wills: ‘Will you write to Ryland if you have not heard from him, and ask him what the Birmingham reading nights are really to be? For it is ridiculous enough that I positively don’t know’. This letter was written on 21 November 1853, with only five weeks to the nights to the readings.

Samina also writes in reference to the readings, that Dickens ‘was a little concerned about how they would be received’. Yet in his letter to Ryland, Dickens said of one of his readings that he knew ‘the power of it with an audience’.

The item is a double-edged sword for while it speaks of the close ties between Charles Dickens and the Institute, it also demonstrates one of the Institute’s failings.. The current management seems to have little understanding of the asset that it has in its affiliated groups, and as this article shows, makes no attempt to capitalize on that knowledge and produce something that is better because it is more accurate.